A creature of its time: the critical history of the creation of the British NHS

Michael Quarterly 2011;8:428–41.

The British National Health Service was formed in 1948, and has since been internationally admired and emulated. This paper seeks to understand the circumstances of its creation: why it could only have happened in this brief window of opportunity at the end of the Second World War. It argues that the structural weaknesses and chronic under-financing in its first few years have been difficult to rectify, but that the British love affair with the concept of a universal free healthcare service has prevented, until now, any serious erosion of its function. It suggests that closer examination of the historical context of the NHS, especially the negotiations that created it, and the concept of policy ‘path dependency’ can help to understand its current crisis.

A scenario

Picture a developed country, experiencing an economic recession, significant expenditure on fighting overseas wars, and social unrest. Struggling independent hospitals are failing to balance their budgets. General practitioners are increasingly unsure about where to refer their patients: to these stressed private institutions, groaning under the weight of recent costly capital projects, or to what are perceived as second class public institutions? The public understand that the government is duty-bound to provide them with some basic health care, but are confused as to where the boundaries lie. The government knows something has to change, but is constrained by funding crises and lack of expert advice. The setting is not Britain in 2011 but Britain in the 1930s. To understand the contemporary debates on the future of the British National Health Service [NHS], it is necessary to understand the circumstances of its creation. Never has history been so critical to the future. It is a tale of personalities, politics and, of course, money.

The British NHS came to life on 5 July 1948 – the ‘Appointed Day’, as it was advertised. This paper will demonstrate why the NHS is a creature of its age: it could not have been created in 1938 or 1958. It exploited a small window of opportunity at the end of the Second World War. I say ‘creature’, as if the NHS is a sentient being. To the British people it perhaps is. The chronology is important – it is 63 years old. Although it is now showing signs of wear and tear, it is still very much alive and the focus of considerable affection. For this reason, it will not die peacefully.

Before the NHS

Health care in Britain before 5 July 1948 was dependent on the wealth of the individual. The state had progressively taken on responsibility for some aspects of health, especially public health, and the health of those deemed worthy of welfare support. One can date this back to the Victorian Poor Law and to the sanitary reforms that initiated compulsory vaccination schemes and disease surveillance. It was ostensibly the pressure of the newly enfranchised working class men after 1867 that prompted the existing political parties – the Liberals and the Conservatives – to appeal to concerns about ill-health (now firmly associated with poverty since the work of Engels and Chadwick), and to offer a more robust state health security net.

This took shape under the reforming Liberal government between 1906 and 1911, which saw the institution of school medical inspections, infant and maternal welfare clinics, and a National Health Insurance [NHI] scheme, part-plagiarised from Bismarck, and tempered by a concern for its cost, and a desire by the government not to be seen as a ‘nanny state’. Panel Doctors were appointed from independent general practitioners [GPs] who owned their own practices. They received a capitation fee from the government for providing basic health care to the working men who had paid the compulsory contribution to the scheme. Most men also continued to pay into the private health insurance and friendly society schemes which covered their wives and children, and who were cared for by the same GPs.* For more information on the pre-NHS health insurance schemes see Gorsky M, Mohan J, Willis, T. Mutualism and health care: British hospital contributory schemes in the twentieth century. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2006. A Ministry of Health was established in 1919, which helped to institutionalise the philosophy that certain health issues were the natural responsibility of the state. Yet this steady expansion of state-funded health services, which required medical staffing, did not sit well with the medical profession. For many, it was a ‘thin end of the wedge’ attack on their freedom from control and ability to determine their own incomes.

Medical practitioners in Britain had become increasingly professionalised during the nineteenth century. The British Medical Association [BMA] was established in 1832 and was closely involved with the passing of the 1858 Medical Act, which created a Medical Register to record those practitioners who held approved qualifications. The General Medical Council, also created by the Act, provided a self-regulatory quality control system for the profession. Other medical professional associations were also formed to represent specific interests, such as hospital consultants, but it was the BMA that usually took on the main role of negotiating with the government on proposed changes to health care services.

Although there had been discussion of going further than the Liberal welfare reforms, the inter-war period saw little change. There had been an innovative report prepared by Lord Dawson in 1920 for the Minister of Health’s Consultative Council on Medical and Allied Services, in which he used his military expertise to propose a reorganisation of Britain’s diverse health care providers into regional hierarchies of primary and secondary facilities (primary being general practice, and secondary referring to hospitals and specialist treatments – the first time these terms were applied to health care).* Ministry of Health, Interim Report on the Future Provision of Medical and Allied Services, Cmd.693. London: HMSO, 1920. The general proposal – that ‘the best means of maintaining health and cutting disease should be made available to all citizens’ was backed up by the report of the Royal Commission on National Health Insurance in 1928, which suggested ‘divorcing the medical service entirely from the insurance system and recognising it along with all other public health activities as a service to be supported form the general public funds’.* Royal Commission on National Health Insurance, Report Cmd.2596. London: HMSO, 1928. This would have forced the pace on greater collaboration between the state’s health care services (mainly municipal hospitals and clinics – some of them former Poor Law institutions) and those provided for the majority of the population through private general practitioners [GPs] and voluntary (independent) hospitals.

By the mid-1930s many of the independent hospitals were experiencing financial crises. Their income, mainly from health insurance schemes and charitable donations, could not keep pace with the costs of medical treatment. In 1891 some 88 per cent of their income had come from gifts and investments; by 1938 this had reduced to 35 per cent and patients now contributed 59 per cent of voluntary hospital income either out of their own pockets or through insurance schemes. It left these hospitals vulnerable to economic conditions. Of the 145 voluntary hospitals in London in 1932, 60 failed to balance their books, and by 1938 these hospitals were pleading with the government for state grants. The plaintive cry: ‘funds urgently needed: beds closed’ suggested to many people that the voluntary hospital sector might not be worth saving.* Timmins N. The Five Giants: A Biography of the Welfare State. London: Fontana Press, 1996, p.104.

Other proposals were emerging, which reflected their authors’ primary concerns. The BMA in 1930 had proposed extending the insurance coverage to the whole population and a co-ordinated regional hospital service. The Socialist Medical Association [SMA] in 1933 proposed a more radical solution – that all healthcare should be provided free at the point of use through one scheme, funded either by taxation or national insurance, and administered by local government.* British Medical Association, A General Medical Service for the Nation. London: BMA, 1930; Socialist Medical Association, A Socialised Medical Service. London: SMA, 1933. This was adopted as official Labour Party policy in 1934. In 1937 the Report on the British Health Services by the think tank PEP [Political and Economic Planning] proposed similar nationalised services, to extend primary health care from the 43 per cent who were currently covered by Panel doctors under NHI to the whole population. This would also have suited many GPs who were not well off, and who supplemented their panel work with sessions in hospitals and occupational health services.

Catalysts for change

From 1938 senior civil servants within the Ministry of Health began to hold discussions on the future of the health services. The Chief Medical Officer, Sir Arthur MacNalty, articulated the need to involve the medical profession from the outset in any change – rather than being seen to impose a system on them. There was lengthy debate led by the Permanent Secretary Sir John Maude on what the most efficient solution would be: extending national insurance cover, or increasing local government involvement. What is remarkable, as Rudolf Klein has pointed out, is the seeming lack of interest of the politicians in generating these policy initiatives. According to the archived correspondence, all the impetus came from the civil servants.* Klein R. The New Politics of the NHS. London: Pearson Educational Limited, fourth edition, 2001, p.7.

At the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939 the government temporarily commandeered all hospitals to form an Emergency Medical Service [EMS], to provide free medical care for certain groups, and to fund the independent hospitals. As the war progressed its remit was extended to cover the majority of British people. The EMS was organised by regions – a good test of the applicability of Dawson’s 1920 model. To facilitate this, the Ministry of Health had commissioned what has since been called the ‘Doomsday Book’ of British Hospitals (a study by the Nuffield Provincial Hospitals Trust) which for the first time collected information on all types of hospitals – their bed capacities, staffing, and funding. This gave some indication of the regional disparities in health care provision. There were 1,545 municipal hospitals run by local government and led by Medical Officers of Health with a total of 390,000 beds. These were often the remnants of the Poor Law, still known by patients under their old names of Workhouse Infirmaries, which often triggered bitter memories of poor quality health care and the lingering whiff of social stigma. There were 1,143 voluntary (independent) hospitals providing 90,000 beds (which ranged from small cottage hospitals with less than 10 beds to the largest and most powerful teaching hospitals in the country).* Committee of Enquiry into the Cost of the National Health Service, Report Cmd.9663. London: HMSO, 1956, paragraph 153. There was little effective cooperation between the voluntary and municipal sectors, and their respective management styles were very different.* Edwards B. The National Health Service: a manager’s tale 1946-1994. London: Nuffield Provincial Hospitals Trust, 1995. The ‘system’, if it could even be called that, was irrational. Specialists were attracted to the wealthier parts of the country that could support their private practices (their honorary hospital consultancies were usually unpaid), but these areas often had the least need of their services. History, not logic, determined that Birmingham had 5.7 beds per 1,000 population while Liverpool had 8.6.* Klein R. The New Politics of the NHS. London: Pearson Education Limited, fourth edition, 2001, p.3.

Further evidence of the extent of ill-health that existed within British society came from the war-time evacuation strategy, in which one and a half million people (including 827,000 children) were moved out of their urban homes, which were at risk of bombing, to lodge with families in safer rural areas. Many of them were from working class families, and they personified the deficient welfare state – malnourished, poorly clothed, rotten teeth. For wealthier host families it was the first time that many of them had encountered real life examples of Britain’s hidden poverty.

Further, and partly as a publicity exercise to life war-time spirits in the depths of the Blitz, the national coalition government commissioned a Liberal academic and civil servant William Beveridge to produce a report on the potential for a post-war welfare reform. Beveridge went further than his brief allowed, and his 1942 report, On Social Security and Allied Services, was an instant public hit – selling over 600,000 copies – unheard of for a dry government publication. The Treasury were dismayed. They had thought he was engaged to tidy up the existing administration, rather than to propose new policy. What Beveridge had produced was a blueprint for tackling what he called the ‘five giant evils’ that currently damaged Britain: squalor, ignorance, want, idleness and disease. The state’s responsibility for the welfare of its citizens should be ‘from cradle to grave’. For health he proposed a comprehensive service, ‘without a charge on treatment at any point’. This egotistical 62 year old civil servant remarked after his report was published:

‘This is the greatest advance in our history. There can be no turning back. From now on Beveridge is not the name of a man; it is the name of a way of life, and not only for Britain, but for the whole of the civilised world.’* Beveridge to Harold Wilson shortly after his report came out. Recounted in Wilson H. Memoirs: the making of a Prime Minister 1916-1964. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1986, p.64.

The Conservatives, led by Winston Churchill, the coalition government’s Prime Minister, had been unhappy to be pushed into action by Beveridge’s audacious and over-remit report, but they had no choice but to allow a series of White Papers to be produced. The one proposing a National Health Service was prepared by Sir John Hawton in 1944, and bore the mark of the Conservative Minister of Health, Henry Willink’s desire (and possibly the ethos of the civil servants involved) to work with existing systems rather than to attempt to plan a new health service from scratch.* Ministry of Health, A National Health Service Cmd.6502. London: HMSO, 1944. However, the White Paper proposed central rather than local government management, while retaining the fundamental principle of free treatment for all. This would require a radical reform to the role of central government – the Ministry of Health would have to move from being an ‘advisory and supervisory and subsidising department’ to become the direct provider of health services.* The National Archives, MH 80/24. A. McNalty (Chief Medical Officer) Minutes of the first of a series of office conferences on the development of the Health Services, 21.9.1939. The issue of how to integrate GPs into a national system was equally challenging. The White Paper acknowledged that a more equitable distribution of GPs was required, but the logic of placing them under local government control was in opposition to the logic of appeasement – the medical profession were clear that they wished to remain free from any sort of state control. Nobody was entirely happy with the 1944 White Paper, but, crucially, no party felt totally alienated by it.

Bevan: divide and conquer

At the end of the Second World War the National Government was dissolved, and at the May 1945 general election the Labour party won an unexpected landslide victory. The new Minister of Health was a Welshman, Aneurin – known as Nye – Bevan (1897–1960). A 45 year-old Welsh former miner, he was one of Labour’s most charismatic and visionary politicians, and at the Ministry of Health proved to be ‘an artist in the uses of power’.* Morgan KO. Labour People – Hardie to Kinnock. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992, pp.204-5. His new proposals went much further than any of the interwar discussions or Beveridge’s proposals. He wanted a national takeover of all hospitals, a health service to be available to all without charge, the end of selling GP practices, and funding primarily by central taxation, with only a small contribution from National Insurance.* For further discussion of the funding options see Gorsky M, Mohan J, Willis T. Hospital contributory schemes and the NHS Debates 1937-46: the rejection of social insurance in the British welfare state. Twentieth Century British History. 2005; 16(2):170-192. The key principle enshrined in the March 1946 Bill was that health was a right, not a commodity to be bought or sold, or subject to market forces.

After many months of negotiation on issues of finance, structure and management, and opposition from Bevan’s Labour Cabinet colleagues, especially Herbert Morrison who championed the cause of local government, the 1946 NHS Act was passed. It was essentially a compromise, and one which set up fundamental structural weaknesses, especially by divorcing medical care (hospitals and some GP work) from health care (local authorities and some GP work).* See Stewart J. Ideology and process in the creation of the British Health Service. J. Policy History, 2002; 14 (2): 113-34, for more details on issues of boundaries, co-ordination and integration with local government. As John Stewart has noted, ‘much of the profession itself was at this stage at best indifferent, at worst actively hostile, to preventive medicine, social medicine and public health’.* Stewart J. The Political Economy of the British National Health Service, 1945-1975: Opportunities and Constraints? Medical History 2008; 52: 463. The Appointed day was set as 5 July 1948: that left only two years in which to set up the administration for Bevan’s planned thirteen regions for England and Wales (and five for Scotland under a separate but parallel Act). Yet this was only the beginning of the battle to create the NHS. Bevan entered into further discussions with the medical profession. He had already established a strategy of divide and conquer, offering substantial concessions to the hospital specialists represented by the royal medical colleges, to try to break their solidarity with the BMA, which drew its strength from the general practitioners. The Act confirmed that teaching hospitals would have their own boards of governors, reporting directly to the Minister of Health; that private patients could be treated in nationalised hospitals; that regional health authorities had executive not just advisory status and would have medical representation, and that hospital specialists would have a new system of merit awards to enhance their NHS salaries.

The BMA, with the popular radio doctor Charles Hill as its articulate spokesman, initially opposed the NHS Act, fearing that it would be too intrusive on professional freedom, and turn all healthcare into a local government service. At the first vote its members rejected it. Bevan held out, choosing to use his Chief Medical Officer, Sir Wilson Jameson, to hold the face to face meetings with the profession’s representatives. It is interesting that Bevan himself credits the successful formation of the NHS to the work of Jameson, but he is seldom remembered.* See Sheard S, Donaldson L. The Nation’s Doctor: the role of the Chief Medical Officer 1855-1998. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical, 2005 for further details on Jameson’s career and his role in the creation of the NHS.

The BMA won concessions which further undermined the structural integrity of the planned NHS. General practitioners were to be on contracts to local Executive Committees, not employees of local or central government; the proposed local government-managed health centres were to be subject to a ‘controlled trial’ and GPs would not be forced to take up residence within them; GPs would be paid on a capitation basis, not the part-salary scheme the 1944 White Paper had proposed. The BMA defeated Bevan’s plans for a Medical Practices Committee, which would have prevented more GPs setting up practice in areas which already were well supplied, and ended the sale of practices. As late as April 1948, the BMA’s members voted not to work within the imminent NHS. In the final plebiscite (which balloted all members of the medical profession) 54 per cent were against further discussions with the Bevan (the consultants were split evenly, the GPs rejected at nearly two to one). As with all large democracies, it is often easier to mobilise general opposition than to secure agreement on specific proposals.* Klein. New Politics of the NHS, p.19.

The early years

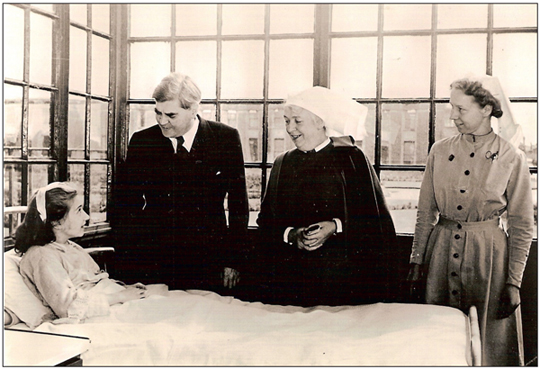

After some last minute negotiations, Bevan got the commitments from the medical profession that he needed. He was later to recall, in his most famous quote, that he had ‘stuffed their mouths with gold’.* Brian Abel-Smith (1926-1996) the health economist and special adviser recalled being told this by Bevan when he had dinner with him at the House of Commons in the mid-1950s. BA-S archive at London School of Economics. BA-S to Julian Tudor Hart 5.11.1973. The NHS was therefore born, on its due date, 5 July 1948. Bevan commented on the scale of his achievement: ‘This is the biggest single experiment in social services that the world has ever seen undertaken’ (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Aneurin Bevan (1897–1960) on the first day of the NHS – 5 July 1948 at a hospital in Manchester.

The public reaction was one of overwhelming relief. For the working classes the threat of doctors’ and hospital bills had been a chronic concern. Now there were no more bills (unless of course the patient opted to jump the NHS queue and pay for private treatment). Although many of the nationalised hospitals were not fit for purpose, there was at least now a government commitment to a more equitable allocation of resources between regions. And the regional health authorities, with their mandate to plan services for populations which ranged from one to five million, were able to develop effective data collection systems, and provide specialist services not required at the district health authority (250,000 population) level. It was an extraordinarily efficient system, and from its outset the focus of international envy.

But it was now the government that worried about the bills, and they had good cause, despite the inherent logic of this part-integrated system. During planning in 1945, the estimate for the annual cost of the NHS had been £170 million. In its first full year of operation – 1949 – it cost £305 million.* See Cutler T. Dangerous yardstick? Early cost estimates and the politics of financial management of the National Health Service. Medical History 2003; 47 (2): 217-38. for more discussion on aspects of the budget, especially how pharmaceutical costs were massively in excess of the pre-NHS predictions. A later Minister of Health, Enoch Powell, writing with the hindsight of 1961, referred to this as a ‘miscalculation of sublime dimensions’.* Powell E. Health and wealth. Lloyd Roberts lecture. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 1962:55; 1-6. Although some of this ‘overspend’ must surely have been tackling the previously hidden reservoir of ill health, the staffing costs were also higher than predicted. It substantiated some political views that Britain should not have attempted such an ambitious scheme so soon after the costly Second World War, which had required an American bail-out and left the country on the verge of bankruptcy.* Fox DM. The administration of the Marshall Pan and British Health Policy. J. Policy History, 2004; 16 (3): 191-211. What must also be factored into the immediate assessment of the relative cost of the NHS are the other demands that were pressing on the UK budget, especially the escalating cost of developing a nuclear ‘deterrent’ and the Korean War rearmament. It was decided that the public should be asked to make some contribution towards paying for ‘the cascades of medicine pouring down British throats’ (Bevan’s phrase).* Quoted in Williams PM. Hugh Gaitskell. London: Jonathan Cape, 1979. Gaitskell was then Chancellor of the Exchequer, and one of Bevan’s main political opponents. Bevan supported the introduction of a one shilling prescription charge. However, he could not tolerate the plan in 1951 to introduce charges to cover glasses and dental treatment and he resigned as Minister of Health.

Arrested development

At the October 1951 general election Clement Attlee’s Labour government fell, and Churchill returned with a Conservative administration which seemed intent on unpicking the new welfare state. They discussed various options, including moving from the taxation based scheme to a fully contributory insurance based one. Rodney Lowe has explored why this did not happen, suggesting that the NHS as a service provided free at the point of delivery was already too entrenched in the British psyche to be withdrawn.* Lowe L. Financing care in Britain since 1939, in Gorsky M, Sheard S. (eds). Financing Medicine: The British experience since 1750. London: Routledge, 2006, pp.242-251. Health was also not one of the Conservatives’ priorities: the Minister of Health was deprived of a seat in Cabinet, and there were no less than seven Ministers responsible for the NHS between 1951 and 1964.

Instead, they did as so many governments have done when faced with politically unpopular decisions, they appointed a Parliamentary committee in April 1953 to enquire into the cost of the NHS. Claude Guillebaud was the nephew of the Cambridge economist Alfred Marshall. He also had studied economics at Cambridge, and made his academic career there. It has been suggested that he was chosen to head the inquiry into the cost of the NHS precisely because ‘of his unexceptionable middle-of-the-road record. His reputation as a «professional just man» was arguably more valuable for disarming Labour critics than for determining that the committee should be economy-minded.’* Webster C. The Health Services since the War Vol. I Problems of Health Care. The National Health Service before 1957. London: HMSO, 1988, p.205. Guillebaud’s committee of four took their time on the inquiry, not publishing their report until January 1956.* Report of the Committee of Enquiry into the Cost of the National Health Service, Cmd.9663, (London, HMSO,1956).

Guillebaud could not have accomplished such a wide-ranging and intellectually innovative review of the NHS without research assistance. Brian Abel-Smith, a young health economist, was appointed to support the committee’s work. He analysed the cost of the NHS (in England and Wales) for the period 5 July 1948 to 31 March 1953 in social accounting terms. He adapted statistics from the Ministry of Health to measure the cost of the service in terms of current productive resources. He analysed the capital expenditure, and assessed the rate of hospital building by comparison with pre-war construction and contemporary American data. He calculated the expenditure required to maintain the present hospital infrastructure (it was estimated that 45 per cent of hospitals predated 1891 and 21 per cent 1861).

Abel-Smith’s analysis showed that whereas the factor cost of the services expressed in actual prices had increased from £375.9 million in 1949–50 to £435.9 million in 1952–3, the cost expressed in constant (1948–9) prices increased only from £374.9 million to £388.6 million. This relative increase in costs was due to additional services and inflation, not, as the Treasury wished to believe, to inefficiency and extravagance. Expressed as a percentage of the gross national product (GNP) the cost of the NHS had actually declined from 3.82 per cent in 1949–50 to 3.52 per cent in 1952–3.

The somewhat unexpected Guillebaud committee’s conclusion was that the NHS was actually very good value for money, and that it demanded a greater share of GNP rather than the current retrenchment, as some politicians were suggesting. The report was explicit: ‘We are strongly of the opinion that it would be altogether premature at the present time to propose any fundamental change in the structure of the National Health Service. It is still a very young service and is only beginning to grapple with the deeper and wider problems which confront it. We repeat what we said earlier – that what is most needed at the present time is a period of stability over the next few years…’* Report of the Committee of Enquiry into the Cost of the National Health Service, Cmd.9663. London: HMSO, 1956, paragraph 148. But the Guillebaud enquiry did admit that there were problems with the system. Sir John Maude, one of the committee members, and a former Ministry of Health senior civil servant, used the report to register what has become a chronic complaint: that the original tripartite structure for the NHS was its major flaw, and that no amount of additional funding would correct this. After the initial news had sunk in, there was growing government dissatisfaction that actually Guillebaud had taken three years to tell them little that was new, but that the report had bolstered the public’s love affair with the new service. The Treasury naturally found it ‘highly disappointing and indeed unsatisfactory’.* Webster C. The Health Services since the War. p.220. The government was forced to accept that dismantling the NHS was not a politically feasible option.

There were further initiatives aimed at curbing the cost of the NHS, especially the pharmaceutical bills. The Treasury and Public Accounts Committee successfully lobbied for the creation of the Voluntary Price Regulation Scheme [VPRS] in 1957. Another policy that the Conservatives exploited was to raise the National Health Insurance contribution to the NHS – from the flat rate of 10d. per week for each contributor introduced in 1948 to 1s.8d. in 1957. There was remarkably little opposition to this move, as both politicians and the public recognised it as ring-fenced money for the NHS. In fact, a second increase to 2s.4d. was adopted only a year later. Thus by 1958 the income from direct charges and from the NI ‘stamp’ contribution totalled almost 20 per cent of the gross cost of the NHS.* Webster C. Conservatives and consensus: the politics of the National Health Service, 1951-1964, in Oakley A, Williams AS. (eds). The Politics of the Welfare State (London, UCL Press, 1994), p.67.

Some Ministers of Health were more creative than others in developing policies that could be seen as improving the NHS, whilst also strengthening accountability of its constituent parts and achieving efficiency savings. Enoch Powell’s Hospital Plan is a prime example.* Powell JE. A New Look at Medicine and Politics. London: Pitman Medical, 1966. Yet, when viewed in the context of Bevan’s vision, and of other western countries in the post-war period, Britain’s record is less than exemplary. The planned health centres failed to materialise, due not only to financial constraints but also to ongoing medical professional obstruction. Only ten were built during the first twelve years of the NHS.* Webster C. Conservatives and consensus: the politics of the National Health Service, 1951-1964, in Oakley A, Williams AS. (eds). The Politics of the Welfare State. London: UCL Press, 1994, p.57. In health expenditure league tables, Britain occupied a mid-position, notably behind Germany, France, Denmark, Sweden, Italy and the Netherlands. Britain’s NHS could never claim to be in the ‘vanguard of health promotion’.* Stewart J. The Political Economy of the British National Health Service, 1945-1975: Opportunities and Constraints? Medical History 2008: 52; 453-470. Charles Webster sees the Conservative’s term of office between 1951 to 1964 as a ‘substantial attack on the NHS, while resource starvation and lack of commitment to improving services prevented the emergence of the range and quality of care intended by the original architects of the service.’* Webster C. Conservatives and consensus: the politics of the National Health Service, 1951-1964, in Oakley A, Williams AS. (eds). The Politics of the Welfare State. London: UCL Press, 1994, p.69. Yet other services such as education, defence, housing and nuclear power did not endure the same attacks.

An integral part of the British psyche

There is not space in this paper to discuss the subsequent changes and reforms (the two words are not synonymous). This historical context of the creation and early years of the British NHS has raised three key issues which are critical to understanding its position and future in 2011. First, the increasing frequency of changes to health care systems in Britain. Lloyd George’s national insurance based system lasted some 37 years; Bevan’s NHS lasted for 26 years until the first major re-organisation in 1974. The more recent chronology demonstrates increasingly shorter periods of experimentation. The ‘system’ is never left long enough to be fully tested, and the experiments are rarely historically informed.

Second, this brief study of the role that various groups – politicians, civil servants, medical professionals – played in the formation of the NHS highlights that we need to understand their respective histories. Even 63 years later, the attitude of the medical profession to change in the NHS remains coloured by the experiences of its predecessors in the 1940s. Although few British doctors today could accurately recount the details behind the formation of the NHS, many will be familiar with Bevan’s quote about stuffing their mouths with gold. This is not the first time that doctors have opposed the government’s health care plans, and we can learn a lot about how to manage such dialogue by looking at the way in which it has been conducted at other flash points: limited prescribing lists, contracts, the introduction of general management, to name some of the most contentious.

Third, the concept of ‘path dependency’ – that policy journeys begun in one direction are subsequently very difficult to alter course – is a very useful framework for analysing why Britain has retained the NHS.* See Pierson P. The new politics of the welfare state. World Politics 1996:48, 143-79. Perhaps it would be more helpful to call it history dependency. The NHS’s history has been the subject of considerable public attention, with the decadal birthdays marked by national celebrations and retrospectives. This should be exploited in a more rigorous way to improve public understanding of potential change.

According to some commentators, the NHS has been in some form of chronic crisis since 5 July 1948. The current NHS crisis is but another variant on previous political themes, all rooted in issues of finance, accountability and efficiency. Yet the way in which the British government is handling this one is different, as the papers by Julian Tudor-Hart and Allyson Pollock in this volume will discuss. What cannot be ignored is the scale of achievement of the NHS: the first health system anywhere in the developed world to give free medical care to the whole population, and paid for not through insurance, which might require a test of contribution, but through general taxation. It remained a beacon through the post-Second World War international recessions, a very visible demonstration of how risk-pooling and might co-exist with a market economy. Its development generated international interest and emulation. It is not the same NHS that Bevan launched, and some have claimed that it was never a ‘health’ service, but a nationalised hospital and sickness service. But it continues to generate unprecedented affection from the millions of Britons who have been cared for by its various parts, from ‘cradle to grave’.

Senior Lecturer in History of Medicine,

University of Liverpool, UK.

sheard@liv.ac.uk