The marketing of medications in Post-Soviet Latvia

Michael 2011;8:258–269.

The Baltic States have had drug manufacturers for a long time. Later, institutes were established where new pharmaceuticals were developed. In the Soviet Union there was practically no marketing of drugs, because shortages and the system of planned economy made any such process quite unnecessary. After the restoration of their independence in 1991, the Baltic States saw complete changes in their pharmaceutical markets. The range of the limited Soviet and Socialist bloc drugs, which always were in short supply anyway, was replaced by pharmaceuticals from the world’s best manufacturers of high tech medications. It took about ten years to bring order to this new market. A free market for pharmaceuticals was established, foreign companies entered the Baltic States, government institutions were set up to register medications, laws were passed, and in preparation for entering the European Union, laws were harmonised with European requirements. Marketing of drugs in the Baltic States was initially aimed at filling the vacuum of information which existed. Later, Western style and professional ways of marketing drugs were adopted, and the aim was always to increase the sales.

It is not easy to come up with an ambiguous conclusion as to what Latvia’s main manufacturing sectors might be today. Twenty years ago, however, it was clear that the main sectors were radio technologies, robot manufacturing, the furniture industry, the textile industry, and the pharmaceutical industry.

Although the situation has changed radically, Latvia remains the leader in pharmaceutical manufacturing in the Baltic States. This is largely due to factories which were established in Soviet times and continue to operate today. Grindeks (leading pharmaceutical company in the Baltic States) was established in 1946 and Olainfarm (one of the biggest pharmaceutical companies in Latvia) in 1972, the latter particularly known for the synthesising of Furagin (Furazidin), an antimicrobial medication, a derivative of nitrofuran.

The drug manufacturers in Latvia were known throughout the Soviet Union. The unquestioned leader at the time was the Institute of Organic Synthesis, which had been established in January 1, 1957 by merging the laboratories of three institutes of the Latvian Academy of Sciences, which all intended to develop new drugs. This institute created and developed 17 different drugs to treat cancer, infections, coronary disease, and other disorders. The institute’s inventions are protected by 63 patents (1). The head of the institute for the first 18 years was Professor Solomon Hiller (191575), who specialised in heterocyclic chemistry and in the way which this science is organised. The institute became the first in the Soviet Union to manufacture peptides, prostaglandins, and cephalosporins. Since 1991 there have been many changes. One of the laboratories of the institute is by now the largest manufacturer of drugs in Latvia and the Baltic States. That is the stock company Grindeks.

«Marketing» of pharmaceuticals in the Soviet Union

We can divide the 20th century in Latvia into three periods: The period of independence from 1918 until 1940, the Soviet era from 1945 until 1991, and the first decade of restored independence 1991–2000.

There were advertisements for drugs during the first and the third period, but not during the second (Figures 1, 2). That applies not only to media advertisements in print and on the television screen, radio and outdoors, but also to advertisements in the specialised medical literature, and at congresses and exhibitions.

During the Soviet period, advertising was unnecessary. Deficits of drugs created a system that was crippled and completely out of line with our understanding of «marketing». E.g. at large medical meetings there were often «travelling pharmacies» which offered non-important medications that were in short supply. An example is Panangin (calcium aspartate/magnesium aspartate). There was also a great demand for ethereal oils and ointments manufactured in Vietnam. The sale of medical and non-medical products at such congresses was an important instrument in the hands of the Soviet regime. It attempted to praise and spread propaganda about the achievements of Soviet medicine.

During this period of no marketing and advertising, it would have been hard to imagine how the situation would develop after the restoration of independence and reinstallment of a free market in Latvia in 1991.

Figure 1. Medical advertising in the Medical Journal of Latvia in 1930-ties.

Figure 2. Medical advertising in Latvian medical magazine in 1990-ties.

One might think that the marketing of medications popped up completely from scratch in the third period. This was not exactly true, as certain very rudimentary attempts at indirect marketing still existed in the Soviet Union, at least in Moscow and some other major cities.

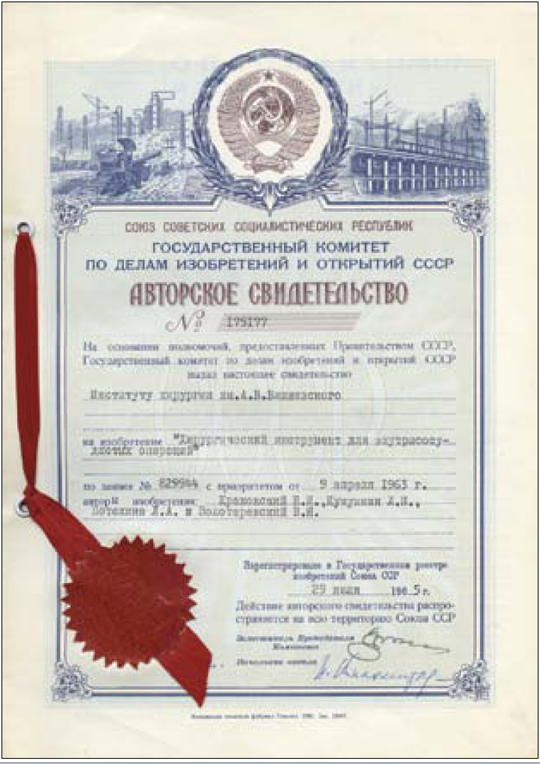

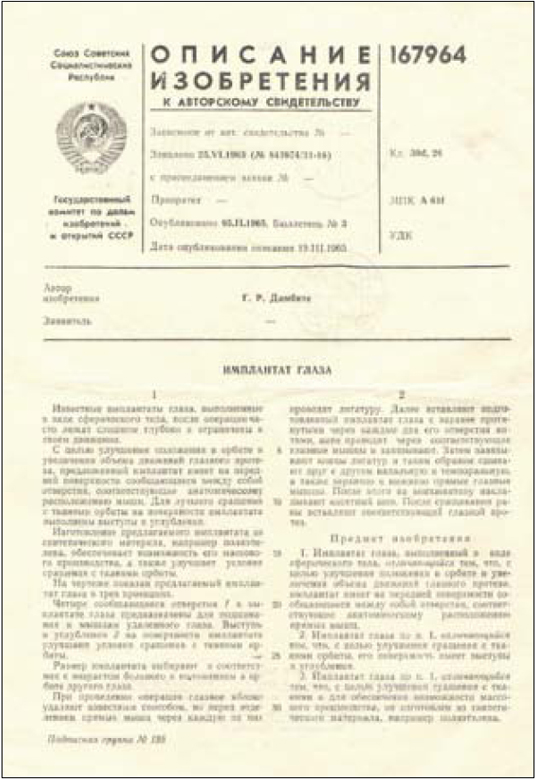

The world’s leading pharmaceutical companies were indirectly represented in the Soviet Union for one simple reason: The way in which patents were registered. No matter how much they wanted to protect their products, foreign manufacturers could not patent their substances as such in the Soviet Union. They could only patent the technologies that were used to create the relevant chemical compound. The practice of refusing to patent local medications survived until 1992. Instead, investors received a certificate which was called «evidence of originality» (Figures 3, 4, 5), but it meant nothing at all, because the state maintained full ownership of all inventions (2).

Another element relevant to the marketing of medications in the Soviet era was the low level of imports. Imports only took place occasionally, because few globally known manufacturers of high-tech medications were interested in selling their products in the USSR. An exception was Cloforan (cefotaxime), which appeared in the Soviet Union at the same time as it did in Western markets (2).

Most drugs were imported under the auspices of the Mutual Economic Assistance Council, which involved the countries that were part of the so-called Socialist bloc.

It must also be noted that throughout the Soviet Union, including the Latvian SSR, the manufacturing of substances was at a high level. Until 1992, the state delivered locally manufactured substanced to all 15 Soviet republics, as well as to most of the Eastern European Socialist countries in which drugs were manufactured (the German Democratic Republic, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Bulgaria, and Yugoslavia, particularly Slovenia and Serbia). From 1975 until 1990, investments in the pharmaceutical industry in those countries were five times higher than in the USSR itself. Export of medical resources from the Soviet Union was dominated by substances, while not more than 10–15 % of imports were of the same (3).

There was another classical element in the marketing of medications – international exhibitions of medications and medical products. These were almost always held in Moscow. Under conditions of shortage, these events became something of a shock to ordinary doctors. When they saw the vast number of products which were offered from the West, they could not know whether any of them were going to be bought for Soviet needs. Nor could they know whether, if such purchases were made, they would be delivered to the people who needed them. There was a bit of «unusual business» in this whole affair. Even though it occurred at a very low level, indeed, the fact is that globally known brands of medications did appear in the Latvian SSR. They appeared in very small amounts, and exclusively through the offices of the Soviet Latvian Ministry of Health Care. Any distribution of such products required the signature of the minister or his deputies. The minister also had to sign any prescription for western made medicaments. Only one pharmacy in the whole Soviet Latvia accepted those prescriptions and handed out the drug.

Figure 3. Evidence of Originality (diploma).1965. From the collection of the Paul Stradin Museum of the History of Medicine in Riga.

Figure 4. Description of the invention. Attachment to the Evidence of Originality1965. From the collection of the Paul Stradin Museum of the History of Medicine in Riga.

Figure 5. Two Certificates of Invention. The first one was issued in May 1990 (the very late of the Soviet period in Latvia). Description in Russian language. Stamped by Soviet Latvian Ministry of Health Care. The second one was issued in June 1991 (the very early period of the Independent Latvia). Description in Latvian language. Stamped by Ministry of Health Care of the Republic of Latvia. Both documents have been signed by the same person.

Arrival of Western pharmaceutical industry on the Baltic market

The first Western companies represented in the Baltics organised their initial work in for different ways: First, they did informational work and began to market drugs through representatives from Finland or Denmark. Second, they delegated the sales of drugs to local pharmaceutical wholesalers as Tamro (distributor of healthcare products in Latvia, as well as being the daughter company of TAMRO, Northern Europe’s largest pharmaceutical wholesaler) and Farmserviss (medical drugs wholesaler in Latvia). Third they set up a legal unit in one of the three Baltic States, usually in the one with the most favourable business laws, to cover all three countries. Fourth, they established a marketing presence with a marketing office in each country.

The latter way became the most usual one. It was also the safest option in the markets of the Baltic States at a time when they had just regained their independence. However, this does not mean that these enterprises only dealt with educational, marketing, and advertising projects. They sold their drugs trough their sales apparatus in other parts of the world, e.g. in Geneva. This meant that local customers paid for the drugs by transferring money to foreign accounts. Due to a new law of commerce, passed in Latvia in 2007, after a transitional period such marketing representative offices were no longer be legal (4–5). Therefore, offices of several foreign companies have converted into limited liability firms.

Irrespective of the form of operations chosen by foreign companies, their job has been to promote the sales of their drugs. At the beginning of the period, classic sales methods from the west were new and unknown in the local market. Even the simplest marketing techniques bemused doctors and other medical professionals. After the shortages of pharmaceuticals that had existed for decades in the Soviet Union and its Baltic republics, any kindness on the part of the pharmaceutical companies as meals, souvenirs, samples, etc. seemed utterly incomprehensive and culturally unacceptable. However, once they overcame this entrepreneurial and cultural shock, it has to be said that doctors rather quickly accepted the new rules of the game. Over a period of time so-called «informative hospitability» from the foreign drug companies became far more generous. E.g. manufacturers offered doctors a chance to attend international congresses. These doctors were always opinion leaders in their medical field. Similar offers were made to health care administrators and to those doctors and bureaucrats who were in charge of drug purchases. This marketing practice was not particularly ethical, given that these local doctors often had poor foreign language skills at the outset, and that once abroad, they were treated in five star hotels, given business class air tickets and special entertainment during the congresses. It is doubtful whether the medical information conveyed in this manner was adequate for the doctors, let alone for their patients, but it certainly stimulated the sales of the sponsors’ drugs.

Some representatives worked directly with doctors. However, the office based staff aimed their efforts on the centralised procurements organised by ministries and hospitals. At a time when the health care budgets of the Baltic States were quite low, only around 2 % of GDP, medical institutions often lacked the money to purchase drugs. A compensation system had not yet been established. Health care administrators organised many bids for tender to get at least a minimal amount of the drugs they needed. Civil servants decided that if they bought medications in large amounts and promoted competition among those who took part in bids for tender, the prices would go down.

Origins of a free market for pharmaceuticals in Latvia: Pharmacies and wholesalers

The new economic circumstances which emerged after 1991 led to the establishment of the first private pharmacies, and, later on, chains of pharmacies. The first full-service player on this market in Latvia was the Zala Aptieka, (the green pharmacy). It was licensed both as a retailer and as a drug wholesaler. Initially this company charged American dollars and not the local currency for their products.

Initially, foreign companies did not trust partners in the newly independent Baltic States and demanded pre-payment for all goods they sold. In the case of Farmserviss, the first Western partner to permit post-payment (for two months), was a little known American wholesaler named Leader.

The first order was worth USD 30 000, and it covered 100-tablet-packages of Aspirin, some Maalox (a combination of almuminium and magnesium hydroxide), and a vanilla-flavoured weight-loss product. These were basically drugs that could be bought off the shelf in American supermarkets, without any need for a pharmacy. However, no antibiotics were included in the first order. Today, of course this purchase seems peculiar. But at that time it was fully in line with the demands of a market that had been heated up by foreign marketing. A form of indirect marketing was a series of local articles about the arrival of new «miracle medications» at the Green Pharmacy. People lined up in long queues to buy 100 tablets of Aspirin and the vanilla flavoured weight loss product for five USD. This happened even though the price was quite high, given the level of income of working people in Latvia.

The initial process proved to be so successful that by end of 1991, Farmserviss had seven pharmacies in Riga and elsewhere in Latvia. As a wholesaler with a chain of pharmacies, Farmserviss became the first business partner in Latvia for several foreign distributors of pharmaceuticals. There were no legal barriers against the new types of distribution of medications in Latvia.

This uncontrolled, yet very successful process was halted in 1992, when drugs, including antibiotics, were purchased in large amounts with money from the World Bank. This crippled the free market drug distribution in Latvia, and continued to affect the market, particularly in terms of the procurement of medications by hospitals, until 1998.

In the years between 1993 and 1995, most of the best known pharmaceutical companies in the world set up some type of operation in the Baltics. Sometimes the business started with the delivery of a single box of drugs which the manufacturer asked a wholesaler to sell.

A system of registration of drugs in line with Western standards was in its infancy at this time. The National Drug Agency in Latvia was established in the autumn of 1996. That was the first serious step in the attempt to bring more order into the local pharmaceutical market. Prior to that, a Certificate of quality usually was enough to distribute a medication. The market was far from saturated. Wholesalers in the Baltic States e.g. had no problems in selling antibiotics. There were few brilliant examples of marketing and advertising. It was clear that there were still many available niches. The market had not yet achieved its full potential (6–10).

Information vacuum in the post-Soviet Baltics

What do doctors think about changes in the pharmaceutical market in the post-Soviet world? Each doctor who was interviewed for this paper said that there was a lack of information about new treatment methods and medications. There were times when pharmaceuticals were available, but without objective information about how they were developed and how clinical trials were conducted. Medical literature in Russian was outdated, new publications in Latvian were extremely rare, and foreign books and periodicals were too expensive for local doctors. There was also a language barrier.

In the course of time, this information vacuum was successfully filled up by representatives of foreign pharmaceutical companies. Their aim was not to engage in aggressive marketing strategies for drugs. Instead, they distributed information about the latest treatments for different diseases

– in most cases, of course, treatment which involved the specific company’s products. These people visited doctors at work, organised medical conferences, and invited doctors to attend company-supported conferences for medical professionals abroad.

Eventually, the pharmaceutical companies operating in the Baltics became more focused in the direct sales of drugs. Marketing processes became more aggressive. Doctors received directly or indirectly material stimuli if they prescribed a specific medication. There were also so-called experience trials in which doctors were paid for each patient who was included in the trial.

The situation began to change as the use of the Internet became more common in Latvia. Prior to that, the doctors had been dependent on the information and honesty of the companies, but now they could obtain information freely, which made them much more independent. Most of the doctors surveyed said that this was a difficult, but very rewarding educational period.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to the staff of the Pauls Stradiņš Museum of the History of Medicine, IMS Baltija, former Farmserviss president Agris Briedis, professor Aivars Lejnieks and professor Sandra Lejniece for the illustrative materials and interviews which they so kindly provided.

Literature

Stradins J. Formation and development of the Latvian Institute of Organic Synthesis over 50 years (1957 – 2006). Chemistry of Heterocyclic Compounds 2007;43,2:127 – 42. (and)

Stradiņš J., Pugačova O. Latvijas organiskās sintēzes institūts. Zinātne 2007; 15 – 21 lpp.

«Патенты,лекарстваиздравоохранение»,декабрь2002:http://expo.rusmedserv.com/ articl1.html.

Фармацевтическаяпромышленность.Импортозамещениечерезинновации: http:/ www.minprom.gov.ru/activity/med/return/1/print.

Komerclikums. Komerclikuma spēkā stāšanās kārtības likums. Rīga: AFS, 2010.

Rīdzinieku veselības aprūpe, 1201 – 2002. Rīga, 2003. – 140.lpp.

VZA. (2010) Latvia’s State Agency of Medicines. [Homepage]. From: http://www.vza. gov.lv/index.php?id=16&top=2&large=&sa=16

Baltic Health. Michael, 2004;1, issue 4.

IMS Health. Emerging Europe. Pharma & Healthcare Insights. August 2007. Issue 16,

Karaskevica J, Tragakes E. Health care systems in transaction: Latvia. European Observatory on Health Care Systems Copenhagen, 2001.

Karhu A. Pharmacy Industry in Russia and in the Baltic States // Publication 50, NORDI series. Lappeenranta 2008. – p.110

Riga Stradin University

Institute of the History of Medicine

Antonijas 1

Riga, LV-1360

Latvia

juris.salaks@rsu.lv