The fight against leprosy in Norway in the 19th century

Michael 2010;7:307–20.* Inaugural lecture by the congress president at the XXII Nordic Congress on the History of medicine, Bergen, Norway, 4 June 2009.

The history of the fight against leprosy in Norway tells how a country in the 19thcentury, poor in financial resources and scientific merits, was able to reach internationally outstanding achievements in microbiology, epidemiology and public health work. These achievements are envisaged as a result of joint efforts of political and scientific-medical movements, in which the right and important actors entered the stage at the right time.

Bringing a public health problem to the attention of the health authorities

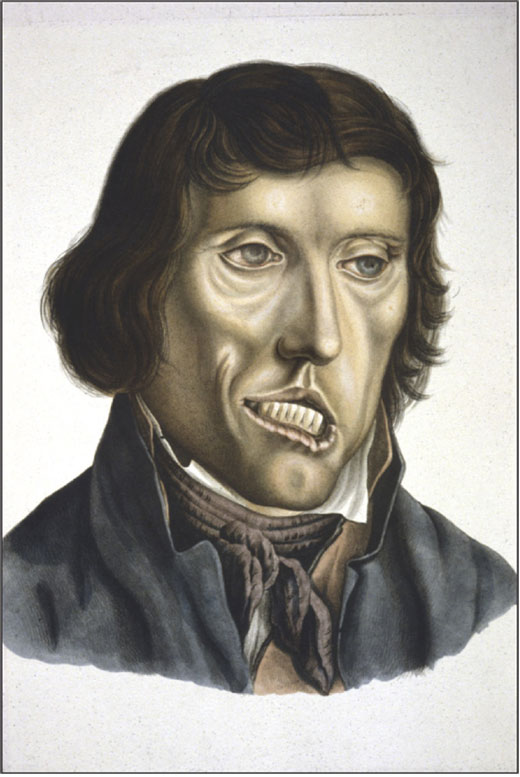

Leprosy had been prevalent in Norway since the Middle Ages. A leprosy hospital, St. George’s in Bergen, had roots back to the late 1300s and had cared for leprosy patients ever since, without attracting great public attention (fig. 1). After a decline, leprosy in Norway was increasing in the 18th century, and in the early 1800s, St. George’s was filled with sufferers from leprosy. At this time, after the Napoleonic wars, the breakdown of the Danish- Norwegian state in 1814 and the subsequent transfer of rule to Sweden, the general conditions in Norway were very poor, and the situation in St. George’s was miserable.

Figure 1. St. George’s Hospital, Bergen. (Photo, Lepramuseet, Bergen)

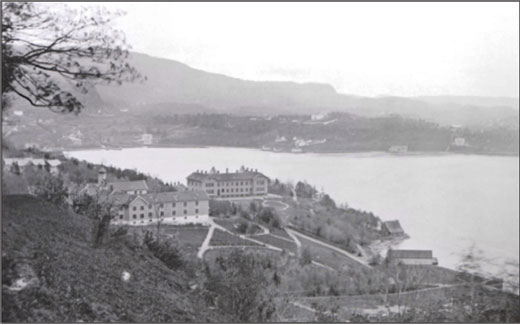

Thus in 1816, the minister of the hospital church, Johan Ernst Welhaven (1775–1828) submitted an article (1) to the Journal of the Swedish Medical Association with pictures of a series of patients (fig. 2). The intention was to call attention to the unbearable conditions, however, no improvements were achieved (2).

Figure 2. Patient in St. George’s Hospital around 1815 (In (1) (Unknown artist))

- a medical movement

Even if the diagnosis of leprosy at that time was imprecise with a number of false positive cases (3), leprosy was established not only as a concept among lay people, but also as a diagnostic entity among the learned, and leprosy was considered an increasing public health problem. In 1832, a physician, J.J. Hjort (1798–1873), was granted a scholarship to shed light on the leprosy problem, visiting the areas where leprosy was most prevalent. He concluded that there was an enormous amount of unmet need for care, that leprosy was curable and that it was a degenerative condition caused by a harsh life (4).

- a political movement

Hjort represented the first initiative in a medical movement, yet with no more success than the religious-philanthropic initiative taken 16 years earlier. However, one year later, in 1833, a parallel political movement was started when the Norwegian viceroy, the Swedish prince Oscar (1799–1859) visited

Prevalent cases |

Subsequent incident cases |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Region |

Year |

n1 |

Period |

n2 |

Annual % of initial cases(i.e. 1856) |

Annual % of immediate previous prevalent cases |

North Norway and Trøndelag |

1856 |

722 |

1856–60 |

348 |

9.6 % |

9.6<[FO]>% |

1860 |

700 |

1861–65 |

349 |

9.7<[FO]>% |

10.0<[FO]>% |

|

1865 |

559 |

1866–70 |

290 |

8.0<[FO]>% |

10.3<[FO]>% |

|

Sunnfjord |

1856 |

433 |

1856–60 |

209 |

9.7<[FO]>% |

9.7<[FO]>% |

1860 |

305 |

1861–65 |

153 |

7.1<[FO]>% |

10.0<[FO]>% |

|

1865 |

246 |

1866–70 |

112 |

5.1<[FO]>% |

9.1<[FO]>% |

|

All other regions |

1856 |

1473 |

1856–60 |

574 |

7.8<[FO]>% |

7.8<[FO]>% |

1860 |

1203 |

1861–65 |

496 |

6.7<[FO]>% |

8.2<[FO]>% |

|

1865 |

1060 |

1866–70 |

395 |

5.4<[FO]>% |

7.5<[FO]>% |

|

Total |

1856 |

2628 |

1856–60 |

1131 |

8.6<[FO]>% |

8.6<[FO]>% |

1860 |

2208 |

1861–65 |

998 |

7.6<[FO]>% |

9.0<[FO]>% |

|

1865 |

1865 |

1866–70 |

797 |

6,1<[FO]>% |

8.5<[FO]>% |

|

St. George’s. On that occasion, a Bergen Member of Parliament, Hans Holmboe (1798–1868) informed the prince that some physicians considered leprosy as curable. Probably encouraged by the royal response, Holmboe, in 1836, proposed to the Parliament the establishment of four leprosy hospitals in Norway for cure and care, a patient census (659 patients or 5 per 10,000) and a Leprosy Commission to further investigate the issue (4). In Norway at that time, the idea of establishing hospitals in order to solve a medical problem had originated in the context of the Norwegian radesyke (probably a non venereal treponematosis) which represented a public health problem at the turn of the 18th century (5).

A remarkable interaction between the medical and political movements occurred in 1839 when the young physician, Daniel Cornelius Danielssen (1815–94) was appointed consultant at St. George’s (fig. 3) (6). Already in 1840, Danielssen was requested by the Ministry of Health to continue his observations of St. George’s leprosy patients aiming at a scientific study of the disease (7). It appears that Danielssen very early on had discovered a way to tap the Norwegian state finances.

Figure 3. Daniel Cornelius Danielssen (1815–1894) (Unknown artist). Lepramuseet, Bergen

From attention to action

Apparently, statements in the learned society suggesting that leprosy was a curable disease had made a great impact in lay opinion. As a consequence, and also as a result of Danielssen’s scientific work, the Parliament, in 1842, decided to establish a research hospital in Bergen for 90 leprosy patients, with the specific objective of developing an effective cure against leprosy (2). Being one of Europe’s poorest countries at that time, this represented an unprecedented effort to solve a serious public health problem. The Lungegaards hospital was opened in 1849 with Danielssen in charge.

Another result of Danielssen’s research was the publishing of ‘On Leprosy’ (Om Spedalskhed) co-authored by C. W. Boeck (1808–75); a comprehensive illustrated book in which the disease was given a definition with an adequate discussion of differential diagnoses. Clinical signs and symptoms were described (fig. 4), and the histopathology of leprosy was established (7). The aetiology was also discussed and based on analyses of pedigrees, leprosy was considered as a hereditary disease. One year later, in 1848, the book was translated into French and in 1855 awarded the prestigious ‘Prix Monthyon’.

Figure 4. Leprosy patient, a non-lepromatous case with a facial palsy (In (4), artist: J.L. Losting (1810–1876)).

The necessity of establishing a leprosy control programme

At this stage, in the early 1850s, it had become obvious that leprosy in Norway resulted in an immense amount of unmet need for care. Furthermore, there was evidence suggesting an increasing magnitude of the health problem with prevalence rates, obtained in special ad hoc censuses, rising from 5 per 10,000 in 1836 via 8 in 1845 to 11 in 1852. Finally, an increasing number of cases near Oslo, in areas where leprosy had been unknown, caused alarming attention with central health authorities (4). The necessity of a leprosy control programme had become evident.

Within the scope of the medical movement, the Permanent Medical Commision of the Ministry of Health in 1851, based on a hypothesis that leprosy was a hereditary disease, proposed the establishing of a number of leprosy hospitals, ensuring sexual isolation of all patients and their descendants in the first and second generation, sterilization of all male patients and setting up of a national registry for all leprosy patients and their relatives. The proposal was not put forward before Parliament by the Ministry (4).

Rather, a far more down to earth proposal was suggested by the Bergen members of Parliament, a hospital for care, which was accepted in 1851 and opened in Bergen in 1857 (fig. 5).

Figure 5. Leprosarium no1 (Pleiestiftelsen for Spedalske no 1) (to the left) and the Lungegaard hospital in Bergen. (In: Harris C.J., Gjerstad J, Irgens L.M., Gogstad A. En kulturhistorisk perle på Kalfaret. Bodoni forlag, Entra Eiendom AS, Bergen 2008.

However, a control programme was still lacking. At the time, there was a general agreement that a control programme aiming at eradication, had to be based on firm knowledge of the aetiology. The current divergent hypotheses suggested that leprosy was

a hereditary disease (D. C. Danielssen)

a degenerative disease caused by a harsh life (J. J. Hjort)

an infectious disease (F. Lochmann (1820–91)

Even if a general agreement was lacking, action was needed, and in 1854 Ove Guldberg Høegh (1814–63) (fig. 6) was appointed Chief Medical Officer for Leprosy. In 1856, a Royal Decree represented an important step towards a national control programme, involving the establishment of the National Leprosy Registry of Norway and setting up of permanent municipality Boards of Health. These Boards of Health became an integral part of general public health work in Norway for more than 100 years. The Leprosy Registry represented the world’s first national registry for any disease (8). These achievements give Høegh a place among the fathers of epidemiology, i.a. together with his contemporary, John Snow (1813–58).

Figure 6. Ove Guldberg Høegh (1814–1863), the founder, in 1856, of the National Leprosy Registry of Norway. (In: Larsen Ø ed. Norges leger 1996, Oslo: Den norske lægeforening, 1996.)

The reasons for establishing a national registry are based on a series of necessities (8):

provision of health care to those in need

epidemiological surveillance of an important public health problem

aetiological research in terms of epidemiology, identifying risk factors aiming at effective prevention

Already in 1856, Høegh prophetically claimed that ‘by processing these data, we shall identify the cause of leprosy’ (9). In 2001, the National Leprosy Registry of Norway was included in UNESCO’s heritage list: ‘Memory of the World’.

The initial part of the control programme was concluded by the erection of another two leprosy hospitals for care, Reknes, Molde (1857) and Reitgjerdet, Trondheim (1861). Together with the three hospitals in Bergen, these hospitals could accommodate 1000 leprosy patients. As the total number of prevalent cases never exceeded 3000, this hospitalization scheme represented an extremely high coverage.

Thus, one might conclude that the leprosy control programme based on an aetiological hypothesis of genetics (the medical movement), had, in actual practice, purely humanitarian objectives in terms of individual care (the political movement).

The discovery of the leprosy bacillus

In 1868, Gerhard Henrik Armauer Hansen (1841–1912) (fig. 7) started his career as a physician at the Lungegaards-hospital in Bergen. In 1873, on 28 February, he saw the leprosy bacillus (M. leprae) for the first time and published his discovery in Norwegian (1874) (10), as well as in English (1875) (11).

isolation as enforced in Norway should be recommended in all countries’ (2).

Figure 7. Gerhard Henrik Armauer Hansen (1841–1912), the discoverer, in 1873, of the leprosy bacillus. (Photo, Lepramuseet, Bergen).

However, general agreement on the significance of his discovery was lacking (9). Already agreed upon criteria, establishing a microorganism as the cause of a disease, could not be fulfilled:

transfer of the disease to experimental animals failed

cultivation of the micro-organism failed

the micro-organism could not be demonstrated in all patients.

This was the background of the Hansen-Neisser interlude 1879–80 (12). During the summer of 1879, A. Neisser (1855–1916) visited Hansen to cooperate in an effort to stain the micro-organism but they were not successful. However, back in Breslau, Neisser succeeded and immediately published the discovery of the leprosy bacillus as his own achievement. Not surprisingly, Hansen reacted and in 1880 published a series of articles in Norwegian (13), German (14), English (15) and French (16) in order to rectify the issue.

This interlude should also be envisaged as a part of the background of the Hansen trial (11). Lack of necessary evidence prompted Hansen to undertake an experiment during the autumn of 1879 by which he inoculated alleged infectious material from a lepromatous patient into the eye of a tuberculoid patient. The experiment caused increasing uneasiness at the hospital and in wider circles. Thus, in 1880, Hansen was sentenced to forfeiture of his post as physician at the hospital, but continued as Chief Medical Officer for Leprosy until his death.

Epidemiological evidence

Actually, the greater part of Hansen’s 1874 publication was epidemiological and derived from the Leprosy Registry, providing evidence that leprosy was an infectious disease. He observed that the fall in incidence was greatest in areas where hospitalization had been most strictly enforced (10). If the disease was hereditary, he argued, the number of new cases during a five year period would be related to the number of cases present when registration started in 1856. However, if leprosy was infectious, the number of new cases would be related to the number of cases present immediately before the five year period.

Hansen observed that the number of new cases as a percentage of the initial prevalent cases in 1856 steadily dropped, while as a percentage of the immediate previous prevalent cases he observed a remarkable constant proportion of 10<[FO]>% new cases per year (Table 1) (10). He considered this observation as evidence that leprosy was infectious.

Additions to the control programme

In consequence of the evidence that leprosy was an infectious disease, the Parliament already agreed in 1877 on the ‘Act for the Maintenance of Poor Leprosy Patients’ (Lov om forsørgelsen af fattige spedalske m.v.). The law represented the discontinuation of an old poor-relief system by which the poor were moved from farm to farm where they were given support (2).

This law was replaced by the ‘Act for Seclusion of Leprosy Patients’ (Lov angaaende spedalskes afsondring og indleggelse i offentlig pleje eller helbredelsesanstalt m.v.) of 1885, which ordered the patients to be hospitalized unless they had their own room at home (2). The law of 1885 was the result of a Hansen initiative as he argued that the decline in incidence, based on data from the Leprosy Registry, was not sufficiently rapid.

Thus, based on epidemiological evidence, leprosy was considered an infectious disease, and public health consequences were taken in terms of laws ensuring isolation of infectious patients.

Evidence of international recognition

Not only Neisser visited Norway to study leprosy. Already in 1873, H.V. Carter (1831–97), Surgeon Major in the British Indian Army stated that ‘The Norwegian control programme seems convincing and parts of it should be introduced in India’ (2).

More specific was a statement by R. Roose (1848–1905) in 1890 that ‘isolation of patients is necessary to restrain the spread of leprosy by infection’ (2).

The final and most influential recognition occurred at the first international leprosy congress in Berlin, 1897: ‘The system of compulsory notification, surveillance and

As a symbol of this international recognition, the second international leprosy congress was organized in Bergen in 1909.

Thus, lack of bacteriological proof as to an infectious aetiology of leprosy did not impede the implementation of the successful Norwegian leprosy control programme as a model in other countries.

Implications and paradoxes

It may be considered as a paradox that, initially with purely humanitarian objectives in terms of individual care, the Norwegian leprosy control programme became most effective against an infectious disease.

A side effect of the control programme with its humanitarian background, represented another paradox. Up to the present, discrimination and stigmatization have no doubt added to the burden of the leprosy patient. Probably, the Norwegian leprosy control programme has contributed to this effect by its isolation in terms of hospitalization and by acting as a role model in other countries. However, many of the patients were seriously ill and led a miserable life at home, with little or no care, necessitating hospitalization. Furthermore, the isolation in Norway was not as rigid as in many other countries.

Even if isolation was an important factor in the fight against leprosy in Norway, it is an enigma that ‘chemical isolation’, rendering the patient non-infectious, has not brought leprosy under control as quickly as expected. Probably, co-factors in addition to M. leprae, are important in the aetiology of leprosy (3).

Finally, one might conclude that medicine and public health politics should be evidence based. However, the history of leprosy in Norway is just one example suggesting that sometimes one has to act without evidence or even against it. And what is evidence? Initially the medical ‘evidence based’ movement was perilous as compared with the non-evidence based political movement.

In broad historical perspectives, the role of the individual has sometimes been questioned. However, in the history of leprosy in Norway significant roles were played by outstanding individuals; Danielssen who paved the scientific and organizational way, Høegh who established the world’s first national health registry and Hansen who for the first time attributed a micro-organism to a chronic disease.

Literature

Welhaven JE. Beskrifning øfver de spetalska i S:T Jørgens Hospital i staden Bergen i Norrige. Svenska Läkare – Sällskapets Handlingar 1816;3:188–220.

Irgens LM. Leprosy in Norway: An Interplay of Research and Public Health Work. Int J Leprosy 1973;41:189–198.

Irgens LM. Leprosy in Norway. An epidemiological study based on a national patient registry. Leprosy Review 1980;51(suppl. 1):1–130.

Hjort JJ. Om spedalskheden i Norge. Christiania: C.C. Werner & Co., 1871.

Kveim Lie A. Radesykens tilblivelse. Historien om en sykdom. Oslo: Universitetet i Oslo, 2008. (Thesis)

Irgens LM, Helle K. Medisinske røtter i Bergen. I: Universitetet i Bergens historie. Bergen: Universitetet i Bergen, 1996. Bind 2 pp 248–67.

Danielssen DC, Boeck CW. Traité de la Spedalskhed on Éléphanthiasis des Grecs. Paris: J.-B. Baillière, 1848.

Irgens LM, Bjerkedal T. Epidemiology of leprosy in Norway: the History of The National Leprosy Registry of Norway from 1856 until today. Int J Epidemiol 1973;2:81–9.

Beretning for 1857 fra Overlægen for den spedalske Sygdom til Departementet for det Indre. Christiania 1858.

Hansen GHA. Undersøgelser angaaende Spedalskhedens Aarsager. Norsk Mag f Lægev 1874;4(Suppl):1–88.

Hansen GHA. On the etiology of leprosy. Brit a Foreign Med – Chir Rev 1875;55:459–89.

Irgens LM. The Discovery of Mycobacterium Leprae. A medical Achievement in the Light of Evolving Scientific Methods. (Commissioned by the journal). Am J Dermatopathol1984;6:337–343.

Hansen GHA. Bacillus leprae. Nord Med Arkiv 1880;12:1–10.

Hansen GHA. Bacillus leprae. Virchow’s Archiv 1880;79:32–42.

Hansen GHA. The bacillus of leprosy. Quart J Microscop Sci 1880;20:92–102.

Hansen GHA. Bacillus leprae, études sur la bactérie de la lèpre. Archive de Biologie 1880;1:1–16.

Professor of Preventive medicine

Locus of Registry Based Epidemiological Research

Department of Public Health and Primary Health Care

University of Bergen

and

Medical Birth Registry of Norway

Norwegian Institute of Public Health

lorentz.irgens@fhi.no