The Norwegian ski ambulance in the Vogesian mountains in 1916

Michael 2008;5:229–39

During the World War I 1914–18 Norwegian students and painters participated for three months in 1916 at the Vogesian front as members of the medical corps, the so called ski ambulance. They evacuated wounded soldiers on skier-pulled sledges through the forest down to roads and ambulance vehicles. Norwegians in Paris had initiated the project as a support to their French friends. The Norwegian painter Per Krohg (1889–1956) was the most well-known of the participants.

Norway and the first World War

The complexity of World War I (1914–1918) may be difficult to perceive for people of today. War was ravaging on many fronts. Main enemies were the triple alliance Germany, Italy, and Austria-Hungary on the one side, with France, England, and Russia on the other. The most important war scenarios took place between Germany and France on the so called Western Front, and between Germany and Russia. Also remote countries became involved, e.g. Japan and the USA. African countries participated, partly with armed forces from the colonies, but there also was fighting on the African continent.

Germany occupied Belgium early in the war. The Western Front was following the Western border of Belgium and the border between Germany and France through the Vogesian hills and mountains separating Alsace and Haute-Saône in eastern France. Alsace had been part of France until 1871, thereafter German until 1914, and French again after 1918.

Many meant that this war would be a short one, but it developed into a long standing conflict where the enemies dug into trenches to hold positions along the borders.

Norway intended to be neutral during World War I, but this was difficult to maintain. There were Norwegian students in both Germany and France; e. g. Norwegian medicine was mainly oriented toward Germany, and German textbooks were standard. On the other side, Norwegian arts and architecture were more connected to the culture of Paris. Norwegian economy was tightly linked to England, especially because of the merchant fleet.

Many Norwegians participated indirectly in the war. Norwegian sailors made up a significant group and several hundred of them experienced torpedo attacks. Some Norwegians also were enrolled in the French Foreign Legion (1). Some Norwegians who had emigrated to the countries in conflict, participated in the war on both sides, however most of them on the French side (2),

Less known these days is that also Norwegian artists and other young Norwegians participated as volunteers on the French side in a period of 1916, exerting a quite spectacular ambulance activity with skis and sledges in Les Vosges, the mountains of norh-eastern France. Wounded soldiers were transported from the front to roads where other medical services could take over.

Material

Occasionally, when history should be written about the Lovisenberg Deaconess Hospital in Oslo, in the files of two senior medical doctors some French military medals were found (3). This added to hints given in the rather abundant literature about the Norwegian painter Per Krohg (1889–1956)(4–6), and made me unveil the story about the Norwegian ski ambulance in the Vogesian mountains during World War I. In addition, descendants of the participants had interesting photographs, items and information about the ambulance service.

What did we find?

Per Krohg is the most renowned participant in the ski ambulance group. However, there were 29 Norwegians involved, even if the number has been discussed. Per Krohg says 19, which is confirmed by a photograph, but Fridtjof Øistein Tidemand-Johannessen says 27.

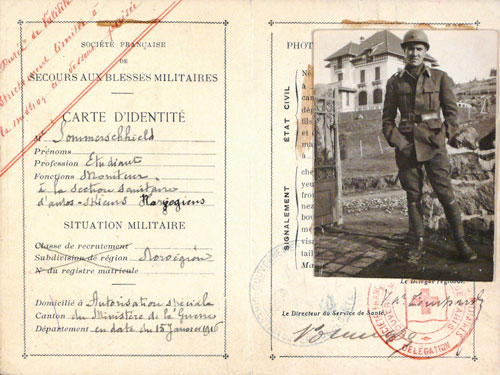

Fridtjof Øistein Tidemand-Johannessen (1893–1976), then a medical student, later head of the radiological department at Lovisenberg Deaconess Hospital, was leader of the group. Otto Jervell (1893–1973), a student who later in life became leader of the medical department of the same hospital, also participated. The third medical student among the volunteers was Henrik Sommerschild (1895–1990) who ended up as a surgeon (figures 1 and 2). All of the three students were awarded French medals of honour, Tidemand-Johannessen even became knight of the French legion of honour. We have a list of the names of most of the participants (7, 8), but there is some inconsequence in the spelling of their names in the different sources.

Figure 1. Military identity card of Henrik Sommerschild. Courtesy of the family. (Photo: IFL).

Figure 2. Helmet and water bottle after Henrik Sommerschild. (Photo: IFL).

According to Nergaard (4) the Norwegian ski ambulance was established after an initiative from the architects Henrik von Krogh and André Peters in collaboration with the Norwegian ambassador to Paris, Fredrik Wedel Jarlsberg (1855–1942) (9). At that time there were many young Norwegians in Paris, students and artists who wished to support their French friends. In Norway some young men were recruited through the Red Cross. Many contacted Tidemand-Johannessen, who later was appointed head of the expedition.

On January 7, 1916 a group of 19 selected young men left Kristiania, dressed in English uniforms, heading for France. Eight participants already were in Paris. However, on arrival in Paris problems arouse. The French ambassador to Norway had reported home from Kristiania that there might be spies among the Norwegians. The uniforms were taken from the newcomers, and they were held back in Paris for some days. The very insisting Norwegian ambassador Wedel Jarlsberg contacted the French president, and the group got their uniforms back.

Figure 3. This picture of La Schlucht was taken in 2008, 92 years after the Vogese fightings. The French-German name reminds us about the changing ownership of the district. (Photo: IFL)

Tidemand-Johannessen (10) reports about their train ride to the small city of Gerardmer, 15–20 km west of the front trenches. They were located in an abandoned villa for some days, before they were transported to the front, which here was situated at 1 100–1 200 m above sea level, near Col de la Schlucht (figure 3), nowadays on the border between Alsace and Haute-Saône in France. At that time this was the borderline between France and Germany, which explains that trenches had been excavated just here. Alsace was French until 1871, German until 1914, and after 1918 again French. This region was famous for its ski sports resorts already before World War I, and still is a popular destination.

The Norwegian camp was a small barrack measuring 3x4 meters. The Norwegians were collaborating with the French chasseurs alpins, Les diables bleus. The mission of the Norwegian group was to transport wounded soldiers from the dressing station close behind the front to the nearest medical field unit, or to a road where a motorized ambulance could pick up the patients. They used a customized sledge, constructed to be pulled by skiers (figures 4 and 5). There were nine men for each of the three sledges, so that they could alternate when pulling.

Figure 4. The ambulance passes through a devastated village. Picture from the «official album» which was presented to the participants when their duty was over. The album from which this photograph was reproduced, belonged to Jervell.

Figure 5. A fallen sentry in the Schlucht pass. From the private photo album of Sommerschild.

According to Tidemand-Johannessen the sledges were much better for the patients than being carried by mules on rough paths. Each mission could last for several hours. However, the front was high up in the mountains, there was a lot of snow and the downhill skiing could be easy. Photographs show that there was less vegetation in the region in the war time than nowadays. Trees had been shot away or burnt down on both sides to secure clear sight for shooting. Therefore the transport of the wounded often had to take place at night, but even this was dangerous because lightning grenades could light up the area. Several times the ambulance personnel were nearly hit by grenades (figure 6). A small burial site in the forest made impression (figure 7).

Figure 6. At the shelling of a grenade. From the private photo album of Sommerschild.

Figure 7: Soldier graves in the forest. From the private photo album of Sommerschild.

The Norwegians served in France for three months. In February and March there was much snow and conditions were favourable. But on April 10, 1916 this ended. It was not possible to use skis anymore. However, the French had learnt how to use sledges, and it is said that the service was reintroduced by themselves the next winter. The Norwegians returned to Paris, where they were celebrated for their successful efforts. And back in Norway, Tidemand-Johannessen gave a lecture in the Club Alpin (11).

Why?

Why did these young Norwegians participate in a war where Norway officially was not involved? And why were they just artists and medical students?

It is easy to understand why Per Krohg wanted to serve at the front. He was born in Norway, but spent much of his childhood and years as a young man in Paris. At the outbreak of World War I in 1914, he lived in Norway with his French girl-friend Lucy Vidil. The couple had planned a return to Paris in the autumn of 1914, but Krohg received his mobilization card and had to stay back in Norway. In spite of this they succeeded in returning to Paris in 1915.

However, it was not easy for a young man to walk around in the streets of Paris, where all other healthy young men had to go to the front. According to the art historian Trygve Nergaard (1938–2002) Krohg had several problematic options. He was not attracted by the idea to join the French Foreign Legion. Should he sign up instead as a volunteer at the front? This was complicated because of the Norwegian neutrality. And how would the bloody war influence him as an artist? The solution was the ski ambulance, a setup which probably was invented to attract Norwegians in Paris, perhaps especially Krohg.

How did young Norwegian men think in 1916, eleven years after the independence of Norway in 1905? We know that many of them were good skiers. E.g. the yearbooks of skier’s organisations reported about spectacular skiing expeditions. Fridtjof Nansen was the hero of the time. The sledges used in the Vogesian mountains were a modified Nansen model. It was made of thin ash wood strings which were tied together without use of nails, and it had supporting bows in front and aft. Thus the sledges were built so they also should be easy to pull uphill again after a downhill patient transport (12).

Why a ski ambulance from just Norway? Per Krohg as a person was probably important in this respect. Although a Norwegian, he obviously felt as a Parisian and wanted to do his tribute to France. Like many other soldiers he married his girl friend just before going to war.

The other Norwegian participants might have had special motives for signing up. They were young, perhaps seeking adventure? In general young artists and architects had a positive relationship to France, especially to Paris. And students, both from medicine and arts had traditions for seeking out. We know that the participant Jervell in his later life worked a lot in sports medicine and muscle physiology and wrote a chapter in the leading textbook of sports medicine (13). This indicates an interest in sports already in early years.

The Norwegian personnel used English uniforms. England and France were on the same side in the war, and Norway had strong ties to England, not least because of the merchant fleet. Even if Norway, as indicated above, also had many students in Germany at that time, the political sentiments in Norway after the 1905 separation from Sweden were mainly in favour of England. Even the Norwegian queen Maud came from England.

The young Norwegians went to France to help, not to make war. They participated as part of the medical corps.

Looking back, the cruel fighting in World War I is difficult to understand. For four years young men manned trenches on each side of the Western front, shooting each other and fighting man against man in the mud, shelled by heavy artillery fire. Erich Maria Remarque (1898–1970) wrote an appalling description of the life of soldiers who had gone to war, often without really realizing why (14). Was the war a tool for nationalists or politicians in countries which wanted to settle their position? Did we meet ideas about liberation or revenge? When these lines are written ninety two years later, World War I simply is felt disgusting and inhuman.

War and visual arts

In art history war motives are repeatedly occurring. Paintings of war scenes might have been ordered by the victor, or depict himself. We find triumphant emperors and generals on horseback with flags and banners swaying in the wind. Vitality, excitement, and victory are elements appalling to the young.

It is a paradox that there was a vivid activity among artists during World War I. The artifacts describe many tragedies, but could also convey humour. When Krohg was asked «How was the war?», he replied «Magnificent and terrible» (4). We find speed, excitement, colours and dramatic effects in the works of Krohg, also from the time prior to his war experiences. The British art historian and critic R. Cork (15) classifies Krohg as «a vivid cubo-futurist».

Futurism originally was a way of writing in literature, inspired from Italy and founded in 1909 by the Italian poet Philippo Tomasso Marinetti (1876–1944), with ideas transferred into visual arts. Paintings depicted vivacity and excitement. It was important to introduce movement into the picture. Krohg painted in this way. In 1912 he presented «An accident» where a horse is running wild in a city street. And one of his paintings from the war is the horrifying scene «Wounded horse in the Vogesian mountains» (1916). However, his «The grenade» (1916, figure 8) is regarded as his most valuable war painting. The explosion is depicted as a friendly flower, but at the same time it is terrible. Other grenades are flying through the air above and soldiers are marching below. The soldiers’ march has been compared to dance. Krohg was himself at this time a popular and professional dancer, giving performances in Stockholm and Kristiania (Oslo).

Figure 8. Per Krohg «The grenade». Oil on canvas, 172,5 x 135 cm. Trondheim kunstmuseum, Norway.

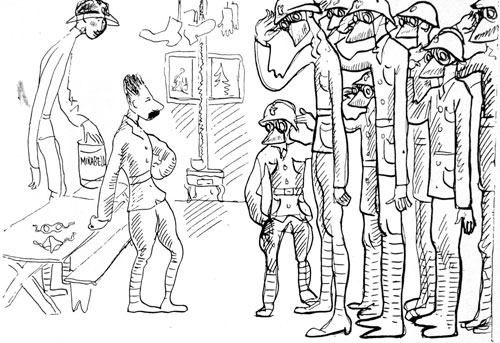

Krohg also left behind humorous sketches from the war, such as of the soldiers trying out helmets and gas masks (figure 9). He sent weekly drawings to the Norwegian newspaper Tidens tegn. The humoristic approachwas a tool to keep mental strength in a war with immense human losses on both sides.

Figur 9. Per Krohg «First exercise with helmets and gas masks» (10).

During World War II Krohg himself became a victim, as he was imprisoned in the Norwegian concentration camp Grini for 13 months.

Per Krohg was a productive painter. His motives contain war and peace. The frescoes named «Ragnarokk» (1933) in the National Library of Oslo (the former University library), the murals in the city hall of Oslo, in the Hersleb public school in Oslo and in the former seamens’ school (Sjømannsskolen) at Ekeberg in Oslo are among works which demonstrate his broad artistic competence. In his later years he had peace as an important motive, conveyed through pictures of flowers and family life. Perhaps the serenity and harmony of his later works reflect his war experiences.

Literature

Angell H. Nordmænd i Fremmedlegionen. Nordmanns-forbundets tidsskrift. Vol. 11, Årg. 1914–1918, 304 – 306.

Ingebretsen HS. Nordmænd i krigen.III. Nordmanns-forbundets tidsskrift Vol. 10, Årg. 1914–1918, 425 – 433.

Larsen Ø. red. Norges leger I-V. Oslo: Den norske lægeforening, 1996.

Nergaard T. Bilder av Per Krohg. Oslo: H Aschehoug & Co., 2000.

Per Krohg. Memoarer. (Written by Henning Sinding-Larsen) Oslo: Gyldendal Norsk Forlag, 1966.

Norske malere. Per Krohg. Preface by Langaard JH, (with 24 colour prints) Oslo: Mittet & Co.,1947.

Wiel T. Spennende dager i Paris. Oslo: Fredhøy forlag A/S, 1932.

Skiambulansen i Vogeserne i 1914. Skiforeningens årbok 1966, 58–60. (The year 1914 in the title is incorrect. The year was 1916.)

Wedel Jarlsberg, F. Reisen gjennem livet. Oslo: Gyldendal Norsk Forlag, 1932.

Tidemand-Johannesen Ø. Den norske skiambulance i Frankrike. Aarbok for foreningen til skiidrættens fremme. Kristiania: Grøndahl & Søn. 1916, 78–93.

Tidemand-Johannesen Ø. L’ambulance du skieurs norvégiens sur le front des Vosges. La Montagne 1916–1918. Revue mensuelle du Club Alpin Français, 1916–1918. No 1 a 3 – Janvier-Mars 1917.

Nansen F. På ski over Grønland. Oslo: H. Aschehoug & Co, 1942.

Jervell O. Idræt og helse. S. 1–96.(sep.pag.): Idrætsboken bind IV. Kristiania: H.Asche-houg & Co.,1923.

Remarque EM. Intet nyt fra vestfronten. København: Gyldendalske Boghandel-Nordisk Forlag, 1929.

Cork R. A Bitter Truth. Avant-Garde Art and the Great War. New Haven and London: Yale University Press in association with Barbican Art Gallery, 1994.

Thanks are due to Kristian Fredrik Jervell and Henrik Sommerschild, sons of ambulance participants, for access to photographs and other private material, and for interesting discussions.

ifro-lar@online.no

retired physician

Sofies gate 5

N-0170 Oslo

Norway