Medical care for industrial accidents in a late 19th century British voluntary hospital – self help, patronage, or contributory insurance ?

Michael 2006; 3:135–56.

Aims

Recent investigations in modern British medical history tend to indicate that health care during this period came in many guises and was offered through a multiplicity of institutional forms. They also suggest a complex network of overlapping systems for insuring against the health risks, from solidaristic friendly society membership to contractual medical aid companies.* See for example, S. Cherry, Medical services and the hospitals in Britain, 1860-1939 (Cambridge, 1996), pp.30, 41-53. Thus any simple assertions about the development of British medical welfare, for instance, from private to public, or local to national, must be erroneous as Professor Paul Johnson has pointed out.* P. Johnson, ‘Risk, redistribution and social welfare in Britain from the poor law to Beveridge’, in M. Daunton (ed.), Charity, self-interests and welfare in the English past (London, 1996), 225-248, p.246. We should recognise a great variety of welfare instruments prevailing in Britain before or even after Beveridge.* J. Harris, ‘Did British workers want the welfare state? G.D.H. Cole’s Survey of 1942’ in J. Winter (ed.) The Working Class in Modern British History (Cambridge, 1983), 200-14, pp.210-11.

This paper is intended to present a case study of the available medical care for industrial accidents in a late nineteenth century British voluntary hospital, North Ormesby Hospital near Middlesbrough in the North Riding of Yorkshire. It is mainly concerned with the implications of the medical care provided by the institution, and the complex nature of welfare instruments through which the working population of the area ensured their safety-net, given that the hospital was supported largely by subscriptions from the industrial workers throughout the period under review. Therefore it would be proper to say at the beginning that from its foundation this hospital had been organised on a different basis in fund-raising from the voluntarism in the sense of the eighteenth century philanthropic and charitable principle.* B. M. Doyle, ‘Voluntary Hospitals in Edwardian Middlesbrough: A Preliminary Report’, North East History, 34 (2001), 5-33, p.9.

The Council Meeting Minute Books of the hospital from 1867 to 1907* North Ormesby Hospital, Council Meeting Minutes Book, 1867-1907, Teesside Archives, H/NOR 1/1. are consulted in order to analyse the relationship in interests between the medical institution, the town’s staple industries of iron & steel and railway, and their workforces. The Case Books from 1861 to 1870* North Ormesby Hospital, Case Book, 1861-1870, Teesside Archives, H/NOR 10/1. and from 1883 to 1908* North Ormesby Hospital, Case Books, 1883-1888, 1885-1908, Teesside Archives, H/NOR 10/2, 3. as well as the Annual Reports of the hospital* North Ormesby Hospital, The First to Fifty Ninth Report of the Cottage Hospital, North Ormesby, Middlesbrough, 1859-1917. are also examined to reconstruct a profile of the age, gender and occupationspecific morbidity of its patients, and trends in the sources of hospital income.

Morbidity as seen in the hospital records

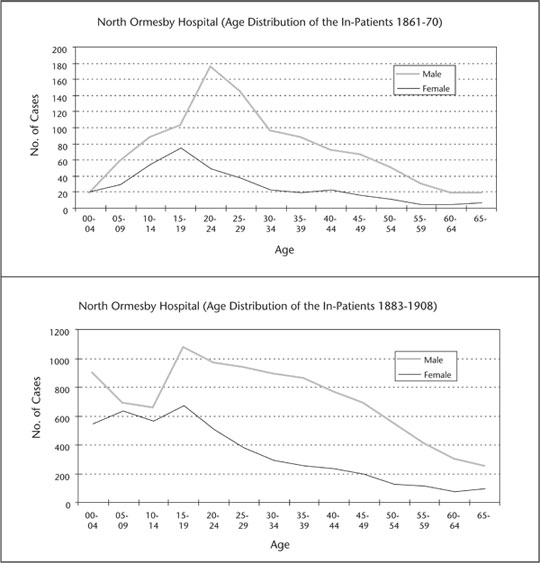

First of all, let us consider overall figures for morbidity as seen in the hospital records, in the two periods, immediately after its erection from 1861 to 1870, and from 1883 to 1908. In both periods, a male bias in the in-patients is apparent, but in the later period, the bias became slightly less salient with males accounting for 67per cent of the total 15,137 in-patients as compared to 72 per cent of the total 1,454 in the earlier period.* Calculated from North Ormesby Hospital, Case Book, 1861-1870, Teesside Archives, H/NOR 10/1, and Case Books, 1883-1888, 1885-1908, Teesside Archives, H/NOR 10/2, 3.

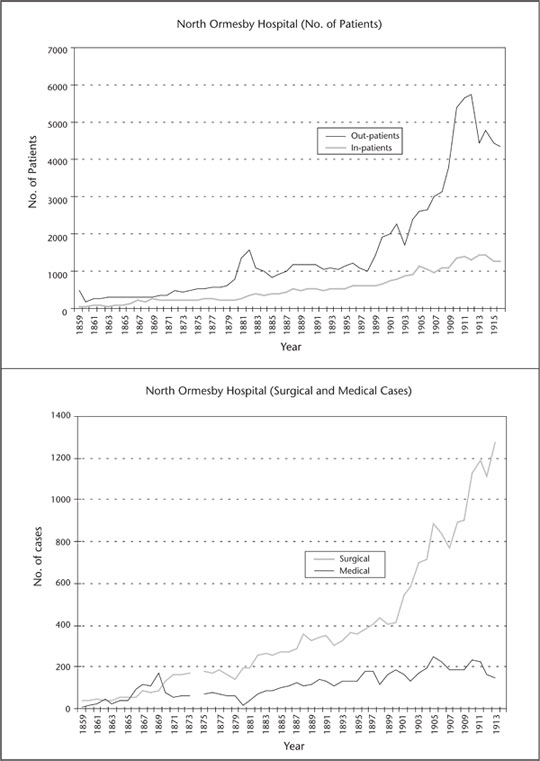

Figure 1 indicates changes over time for half a century in the number of in-and out-patients admitted as well as in the composition of surgical and medical cases.* Calculated from North Ormesby Hospital, The First to Fifty Ninth Report of the Cottage Hospital, North Ormesby, Middlesbrough, 1859-1917. From the opening of the hospital, out-patients outnumber in-patients, which seems rather natural, given the accommodation and expenses for nursing care for the in-patients. On average, the number of outpatients was virtually twice that of in-patients, and at the beginning of the twentieth century, there were considerably more of the former than the latter.

Figure 1: North Ormesby Hospital (Patients)

It is interesting to note that except for a very short period in the late 1860s, the hospital accommodated many more in-patients suffering from surgical rather than internal, medical illnesses. This seems to reflect one of the features of morbidity as seen among the people living in the Middlesbrough area in the late nineteenth century, especially among males.

If we look at gender- and age-specific distributions of the in-patients (See Figure 2), we will notice that between the two periods, there occurred some remarkable changes in the age structure of the in-patients. In the first period, the highest point for males appears among the age groups of 20 to 24 and then of 25 to 29, whereas in the second period, a peak is found in younger age group of 15 to 19 with older age groups from 20 to 24 onwards showing higher levels throughout. The other marked change is discernible in the distributions of infant and child patients, especially in the male age group from 0 to 4 years of age, which in the second period occupy significant proportions.* Males aged 0-4 comprise 8.9 per cent , with females of the same age group occupying 11.3 per cent of the total of 10,068 male, and 4,807 female in-patients.

Figure 2: North Ormesby Hospital (Age Distribution of the In-Patients)

This is likely to be accounted for partly by the changes in the age structure of the population from the 1880s onwards, dependent upon the decreasing in-migration of the age groups of 20 to 24, and from 25 to 29, due to the staple iron & steel industry of the town being somewhat diminished.* Based on the record linkage work of the census enumerators’ books, 1851-61, 1861-71 and 1871-81, HO 107/2383, RG 9/3685-3689, RG 10/4893, RG 11/4851, Public Record Office. As for the development of the iron and steel industries in Middlesbrough during the period, see for example, A. Birch, The Economic History of the British Iron and Steel Industry 1784-1879, (London, 1967), p. 333. I. Bullock, ‘The Origins of Economic Growth on Teesside 1851-81’, Northern History, 9 (1974), pp. 85-96. W. Lillie, The History of Middlesbrough, an Illustration of the Evolution of English Industry (Middlesbrough, 1968), pp. 96-109. D. Taylor, ‘The Infant Hercules and the Augean Stables: A Century of Economic and Social Development in Middlesbrough, c.1840-1939’ in A.J. Pollard (ed.), Middlesbrough, Town and Community 1830-1950 (Phoenix Mill, 1996), pp.53-80. It also seems to have been caused by the fact that towards the end of the nineteenth century, not only did adult males have a claim to the care provided by the hospital, but their wives and children could also increasingly expect to be received into the hospital as appropriate. From 1866 onwards, a special ward for sick children had been set apart.* The Eighth Annual Report of the Cottage Hospital, North Ormesby, Midlesbrough, p.3. These facts suggest changes occurring between the two periods in the fundraising policy of the hospital. For instance, the changes might have resulted from the hospital’s efforts to increase contributors by providing greater access to their dependants.* See S. Cherry, ‘Beyond National Health Insurance. The Voluntary Hospitals and Hospital Contributory Schemes: A Regional Study’, Social History of Medicine, 5, 4(1992), 455-82, p.480.

The most frequent cause of admission for males in the first period is, as is shown in Table 1, from accidents; for instance, injuries, burns, and fractures, whereas women are mostly admitted for internal diseases, such as rheumatism, abscess, and debility. In the second period, the picture is almost similar. For males, surgical cases are also predominant with frequent ailments being compound and simple fractures, burns, bruises and contusions, whilst females are frequently admitted from ulcer, chorea, anaemia, tonsils and adenoids, and tuberculosis, all of which are internal and medical illnesses. Duration of in-patient treatments for females in later period, 34.4 days on average, was slightly longer than that for males, 31.1 days on average, which seems to indicate decreased emphasis upon the acute sick for women.* For the national average of length of stay in voluntary hospitals during the period, see R. Pinker, English Hospital Statistics 1861-1938 (London, 1964), p.111.

For the accidental cases, injuries to feet, legs, ankles and backs are conspicuous. These injuries were mainly due to workplace accidents both in the iron works, and upon the railways. As the compilers of the annual reports of the hospital during the period often grieved, the burns were of the most frightful kind, chiefly from molten iron.* For example, Annual Report of the Cottage Hospital, Middlesbrough, 1862, p.2. Compound and simple fractures together with burns and injuries account for almost half of the causes of death in the first period, whilst in the second period, the most frequent causes of death are also from accidental cases of fractures and burns, comprising 22 per cent of the total deaths of 568 (See Table 2).

(1861–1870) | |||

Male |

Female |

||

injury |

191 |

rheumatism |

28 |

burn & scald |

125 |

abscess |

27 |

fractures |

122 |

debility |

26 |

rheumatism |

82 |

ulcerated legs, etc. |

24 |

abscess |

49 |

burn |

20 |

ulcerated legs, etc. |

47 |

injury |

14 |

crushed legs, etc. |

35 |

conjunctivitis |

13 |

bronchitis |

29 |

bronchitis |

12 |

conjunctivitis |

21 |

chorea |

11 |

phthisis |

20 |

synovitis |

11 |

others |

255 |

others |

165 |

Total |

976 |

Total |

351 |

(1883–1908) | |||

Male |

Female |

||

fractures |

1,082 |

ulcer |

253 |

burn & scald |

689 |

chorea |

193 |

bruise |

502 |

anaemia |

177 |

contusion |

327 |

tonsil and adenoid |

177 |

ulcer |

304 |

tuberculosis |

169 |

inguinal & other hernia |

234 |

abscess |

149 |

abscess |

223 |

gastric ulcer |

135 |

tuberculosis |

223 |

burn & scald |

114 |

crush |

210 |

eczema |

92 |

rheumatism |

206 |

necrosis |

92 |

laceration |

204 |

rheumatism |

90 |

pneumonia |

150 |

carcinoma & cancer |

82 |

bronchitis |

141 |

fractures |

79 |

sprain |

131 |

keratitis |

70 |

necrosis |

127 |

dyspepsia |

63 |

others |

5,315 |

others |

2,872 |

Total |

10,068 |

Total |

4,807 |

North Ormesby Hospital, Case Book, 1861–1870, Teesside Archives, H/NOR 10/1, North Ormesby Hospital, Case Books, 1883–1888, 1885–1908, Teesside Archives, H/NOR 10/2, 3

Male | |||||||

1860 – 1870 |

1883 – 1908 |

||||||

No |

% |

No |

% |

||||

compound & simple fractures |

15 |

26.3 |

compound & simple fractures |

90 |

15.8 |

||

injury |

7 |

12.3 |

pneumonia |

52 |

9.2 |

||

burn & scald |

6 |

10.5 |

burn & scald |

37 |

6.5 |

||

phthisis |

6 |

10.5 |

phthisis & tuberculosis |

25 |

4.4 |

||

abscess |

4 |

7.0 |

strangulated hernia |

12 |

2.1 |

||

bronchitis |

3 |

5.3 |

bronchitis |

12 |

2.1 |

||

others |

16 |

28.1 |

others |

340 |

59.9 |

||

Total |

57 |

100.0 |

Total |

568 |

100.0 |

||

Female | |||||||

phthisis |

2 |

25.0 |

tuberculosis |

16 |

7.0 |

||

burn & scald |

1 |

12.5 |

burn & scald |

15 |

6.5 |

||

cardiac diseases |

9 |

4.0 |

|||||

strangulated hernia |

9 |

4.0 |

|||||

cancer |

7 |

3.0 |

|||||

others |

5 |

62.5 |

others |

173 |

75.5 |

||

Total |

8 |

100.0 |

Total |

229 |

100.0 |

||

North Ormesby Hospital, Case Book, 1861–1870, 1883–1888, 1885–1908, Teesside Archives, H/NOR 10/1, H/NOR 10/2, 3.

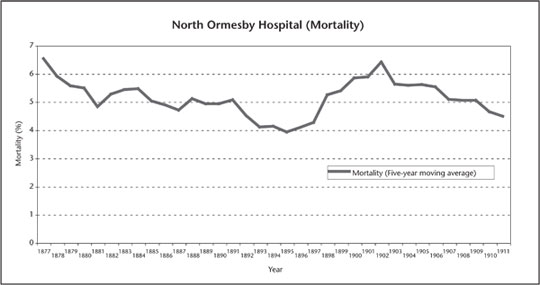

Hospital mortality in both periods was more than 5 per cent on average with a male mortality of 6.0 per cent (See Figure 3).* Calculated from North Ormesby Hospital, The First to Fifty Ninth Report of the Cottage Hospital, North Ormesby, Middlesbrough, 1859-1917. This was clearly higher than those observed in other voluntary hospitals, for instance, 3.1 per cent for the male in-patients in the General Infirmary at Leeds at the beginning of the 19th century.* Hospital mortality in the General Infirmary at Leeds has been calculated from Admission and Discharge Registers of the General Infirmary of Leeds, 1815-17, Leeds District Archives, Sheepscar Library. Causes of death and hospital mortality in North Ormesby Hospital have been calculated from North Ormesby Hospital, Case Book, 1861-1870, 1883-1888, 1885-1908, and The First to Fifty Ninth Report of the Cottage Hospital, North Ormesby, Middlesbrough, 1859-1917. Consumers of medical services, chiefly of the male manual workers employed in heavy industries, living in a physically hazardous environment, had a strong influence upon the hospitalisation in this area.

Fund-raising

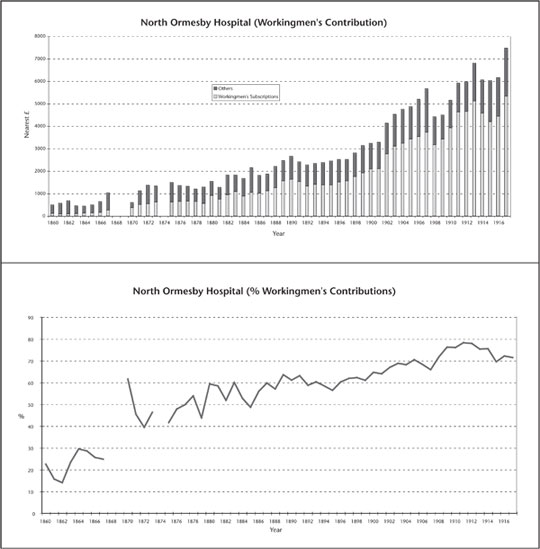

Figure 4 indicates the proportions of the subscriptions and donations offered by the employees of various firms in the Middlesbrough area of all the ordinary subscriptions and donations received by the hospital.* Calculated from North Ormesby Hospital, The First to Fifty Ninth Report of the Cottage Hospital, North Ormesby, Middlesbrough, 1859-1917. It is impressive to note that workers’ contributions to the hospital fund were con- siderable throughout the period. Their contribution accounts for more than half of the hospital funds on average. Towards the end of the 19th century, shares of the hospital’s ordinary income derived from workers’ subscriptions rose rapidly to more than 60 per cent. At the beginning of 20th century, the hospital was run almost entirely from workers’ subscriptions. Thus it could safely be said that throughout its history from 1859, this hospital relied to a great extent on the workmen’s contributions for its fundraising.* For the fund-raising of the hospital in the twentieth century, see R. Lewis, R. Nixon, and B. Doyle, Health Services in Middlesbrough: North Ormesby Hospital 1900-1948, Centre for Local Historical Research, University of Teesside (Middlesbrough, 1999), pp.9-16. B. Doyle and R. Nixon, ‘Voluntary Hospital Finance in North-East England: The Case of North Ormesby Hospital, Middlesbrough, 1900-1947’, Cleveland History, 80 (2001), 5-19, pp.8-14.

Figure 3: North Ormesby Hospital (Mortality)

The same tendencies were seen in the institutions of other heavy industry areas, like Glasgow, Sheffield, Sunderland, Newcastle or Swansea, where accidents, emergencies and environmental diseases were prevalent.* S. Cherry, ‘Before the National Health Services: financing the voluntary hospitals, 1900-1939’, Economic History Review, 50 2(1997), 305-326, pp.318, 324. Yet, even compared to these institutions, North Ormesby Hospital’s sources of income were extremely concentrated on the collections from these heavy industry workers, which is probably rare in the history of British hospital development during the period under observation.* For the workmen’s contributions in selected London and provincial voluntary hospitals, see Pinker, Statistics, pp.152-4.

Differences in the finance and fund-raising activities between this institution and other hospitals are worth noting. Table 3 compares the subscribers for North Ormesby Hospital in 1876 to those for the General Infirmary at Leeds in 1857.* The Eighteenth Annual Report of the Cottage Hospital, North Ormesby, Middlesbrough, 1876, pp.10-13, The Annual Report of the State of the General Infirmary, at Leeds, from September 29th, 1856, to September29th, 1857. The proportions of subscriptions collected from the employees in the Middlesbrough area account for as much as 65 per cent of all the subscriptions, whereas those from the companies cover less than one-tenth of the contributions from the workers, that is, only 5.5 per cent. As for individuals, the amounts from the peerage and gentry comprised 9 per cent, whilst the ordinary lay people contributed 4 per cent.

Figure 4: North Ormesby Hospital (Workingmen’s Contributions))

In contrast to this pattern of fund-raising, Leeds General Infirmary shows a more even distribution in subscriptions. As the General Infirmary at Leeds didn’t adopt contributory scheme procedures, it did not receive any contributions from workmen as a body. Rather the Infirmary relied much more on the wealthy landed interests in the West Riding of Yorkshire. The peerage and gentry contributed 22 per cent of all the subscriptions to the Infirmary.

North Ormesby Hospital 1876 |

General Infirmary at Leeds 1857 |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Subscribers |

No. Of Cases |

Amount £ |

% |

Subscribers |

No. Of Cases |

Amount £ |

% |

|||||||

Companies |

10 |

53.4 |

5.5 |

Companies |

174 |

482.5 |

20.8 |

|||||||

Friendly Societies |

3 |

12.6 |

1.3 |

Friendly Societies |

9 |

29.4 |

1.3 |

|||||||

Poor Law Unions |

2 |

12.6 |

1.3 |

Poor Law Unions |

7 |

45.2 |

2.0 |

|||||||

Overseers of the Poor |

Overseers of the Poor |

11 |

45,2 |

2.0 |

||||||||||

Other Organisations Individuals |

3 |

4.4 |

0.4 |

Other Organisations Individuals |

4 |

40.3 |

1.7 |

|||||||

Aristocrats |

3 |

17.1 |

1.8 |

Aristocrats |

23 |

123.4 |

5.3 |

|||||||

Gentry |

19 |

68.1 |

7.0 |

Gentry |

119 |

390.3 |

16.8 |

|||||||

Ecclesiastical |

7 |

12.6 |

1.3 |

Ecclesiastical |

45 |

110.5 |

4.8 |

|||||||

Lay |

Mr. |

18 |

23.3 |

2.4 |

Lay |

Mr. |

396 |

761.3 |

32.9 |

|||||

Mrs. |

10 |

13.6 |

1.4 |

Mrs. |

93 |

202.4 |

8.7 |

|||||||

Miss |

9 |

7.8 |

Miss |

40 |

86.1 |

3.7 |

||||||||

Workers at various Co. |

631.8 |

65.0 |

||||||||||||

Hospital Sat. & Sun. Fund |

114.5 |

11.8 |

||||||||||||

Total |

971.8 |

100.0 |

921 |

2,316.6 |

100.0 |

|||||||||

The Eighteenth Annual Report of the Cottage Hospital, North Ormesby, Middlesbrough, 1876, pp 10–13, The Annual Report of the State of the General Infirmary at Leeds, from September 29th, 1856 to September 29th, 1857.

Also among the important supporters of Leeds General Infirmary were the rising bourgeoisie of manufacturers and merchants, the petite bourgeoisie consisting of shopkeepers and professionals, as well as other middle class people. Thus contributions from these lay individuals are of primary importance, forming more than 40 per cent. They seem to have exploited the voluntary hospital system, seeking some sort of respectability and patronage which a recommendation to hospitals might have brought, in return for subscribing to a fund for medical facilities. More importantly, subscriptions collected from industrial concerns, mainly the textile companies based in the Leeds area, account for 21 per cent of total subscriptions.* For the urban morbidity and the fund-raising of the General Infirmary at Leeds at the beginning of the nineteenth century, see M.Yasumoto, Industrialisation, Urbanisation, and Demographic Change in England (Nagoya,1994), pp.113-156.

On the other hand, with the exception of Snowden and Hopkins Iron Works, having subscribed a total of 5 pounds sterling, no companies made any contributions in 1860 in the locality in question.* The Cottage Hospital Report for 1860, p.3. So that, in fact, workers originally financed this hospital themselves. In order to show the relative importance in contributions to the hospital covering the period from 1860 to 1881, proportions of the total contributions provided by the companies and their employees are shown in Table 4.* Calculated from North Ormesby Hospital, The First to Fifty Ninth Report of the Cottage Hospital, North Ormesby, Middlesbrough, , 1860-1881.

Name of Company |

Company Contribution |

Employees Contribution |

Total amount |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

£ |

% |

£ |

% |

£ |

% |

|

Cochrane & Co. |

9 * |

5.6** |

152 |

94.4 |

161 |

100.0 |

Bell Brothers |

14 |

23.0 |

47 |

77.0 |

61 |

100.0 |

Gilkes, Wilson, Pease & Co. |

10 |

25.0 |

30 |

75.0 |

40 |

100.0 |

Clay Lane & South Bank Iron Works |

0 |

0.0 |

55 |

100.0 |

55 |

100.0 |

Gjers, Mills & Co. |

0 |

0.0 |

15 |

100.0 |

15 |

100.0 |

Samuelson & Co. |

5 |

100.0 |

0 |

0.0 |

5 |

100.0 |

North Eastern Railway |

10 |

28.6 |

25 |

71.4 |

35 |

100.0 |

48 |

12.9 |

324 |

87.1 |

372 |

100.0 |

|

*: Average £ per annum **: % contribution to each company

North Ormesby Hospital, The first to fiftyninth Report of the Cottage Hospital, North Ormesby, Middlesbrough, 1860 – 1881.

Throughout the period, the total contribution from six major iron works and the local railway company amounted to less than one-seventh of the amount from their employees. Among them, Clay Lane and South Bank Iron Works and Gjers, Mills and Co. made no contributions at all, whereas their workers contributed totals of 55 and 15 pounds sterling respectively on average. The fact seems rather striking when we consider the number of patients sent in by these companies.

Among the companies sending their employees and their families to the hospital, Cochrane and Co., sent the highest number, as much as 30 per cent of all the male patients suffering from surgical cases, and 17 per cent for the male medical cases in the first period.* Calculated from North Ormesby Hospital, Case Book, 1861-1870. They recommended 13 per cent of the male and 9 per cent of the female in-patients in the second period (See Tables 5 and 6).* Calculated from North Ormesby Hospital, Case Books, 1883-1888, 1885-1908. However, this company contributed a total of only 9 pounds sterling on average, throughout the period. By contrast, their employees subscribed as much as 152 pounds sterling on average.

It was often reported in the Council Meeting Minutes Books during the period that ‘The Council would contrast the sum contributed by the working men with the small sum, which has been contributed by the employers of labour’ or that ‘working men who have so nobly assisted themselves deserve a little more encouragement at the hands of those who are owners of capital’.* The Fifteenth Annual Report of the Cottage Hospital, North Ormesby, Middlesbrough, 1873, p.7 The Council Meeting Minutes Books also noted ‘the Owners of Works whose subscriptions have not covered the cost of patients sent in by them’.* North Ormesby Hospital, Council Meeting Minutes Book, 1867-1907, Teesside Archives, H/NOR 1/1, Oct. 8, 1879. Although it looked as if the ironmasters and railway company began to support joint contributory sick-pay schemes, companies’ contributions were clearly minimal as compared to those provided by their workers.* As regards the employers’ contributions to the voluntary hospitals based on contributory schemes in East Anglia in the early twentieth century, see S. Cherry, ‘Beyond National Health Insurance’, pp.478-9.

Male Surgical Cases | ||||||

Companies |

Diseases |

|||||

Names of companies |

Occupations |

No. |

% |

Names of diseases |

||

Cochrane & Co. |

Ironworks |

163 |

30. 9 |

Injury |

135 |

|

Bell & Brothers Co. |

Ironworks |

36 |

Burn & Scald |

97 |

||

Gilkes, Wilson & Co. |

Ironworks |

22 |

Fracture |

82 |

||

Hopkins & Co. |

Ironworks |

22 |

Crush |

29 |

||

Backhouse, Dixon & Co. |

Shipbuilding |

20 |

Contusion |

7 |

||

Bolckow, Vaughan Co. |

Ironworks |

16 |

Wounds |

6 |

||

Stockton & Darlington Railway Co. |

Railway |

15 |

Others |

18 |

||

Jones, Dunning & Co. |

Ironworks |

12 |

||||

Other Companies |

58 |

|||||

Total |

372 |

69.9 |

Total |

374 |

||

Others |

33 |

6.2 |

||||

No recommendations |

127 |

23.9 |

||||

Total |

532 |

100.0 |

||||

Male Medical Cases | ||||||

Companies |

Diseases |

|||||

Names of companies |

Occupations |

No. |

% |

Names of diseases |

||

Cochrane & Co. |

Ironworks |

75 |

17.0 |

Rheumatism |

40 |

|

Gilkes, Wilson & Co. |

Ironworks |

19 |

Ulcerated legs |

27 |

||

Bolckow, Vaughan Co. |

Ironworks |

14 |

Abscess |

19 |

||

Bell & Brothers Co. |

Ironworks |

13 |

Bronchitis |

11 |

||

Backhouse, Dixon & Co. |

Shipbuilding |

11 |

Phthisis |

6 |

||

Hopkins & Co. |

Ironworks |

11 |

Pneumonia |

6 |

||

Other Companies |

30 |

Diseases |

6 |

|||

Inflammation |

6 |

|||||

Others |

53 |

|||||

Total |

173 |

39.0 |

Total |

174 |

||

Others |

73 |

16.4 |

||||

No recommendations |

198 |

44.6 |

||||

Total |

444 |

100.0 |

||||

North Ormesby Hospital Case Book, 1861 – 1870, Teesside Archives, H/NOR 10/1.

Recommenders |

Number of Patients admitted |

% |

|---|---|---|

Male | ||

Cochrane & Co. |

1,277 |

12.7 |

Emergency |

539 |

5.4 |

Raylton Dixson & Co. |

477 |

4.7 |

Cargo Fleet Iron Works |

410 |

4.1 |

North Eastern Railway |

357 |

3.5 |

Wilson, Pease & Co. |

344 |

3.4 |

Bolckow & Vaughan Co. |

285 |

2.8 |

Sadler & Co. |

269 |

2.7 |

Anderston Foundry |

239 |

2.4 |

Normanby Iron Works |

237 |

2.3 |

Dorman Long & Co. |

208 |

2.1 |

Bell Brothers |

186 |

1.8 |

Clay Lane Iron Works |

126 |

1.3 |

Accident |

86 |

0.9 |

Others |

5,028 |

49.9 |

Total |

10,068 |

100.0 |

Female | ||

Cochrane & Co. |

428 |

8.9 |

Emergency |

204 |

4.2 |

Bolckow & Vaughan Co. |

180 |

3.7 |

Dorman Long & Co. |

178 |

3.7 |

North Eastern Railway |

162 |

3.4 |

Cargo Fleet Iron Works |

129 |

2.7 |

Anderston Foundry |

118 |

2.5 |

Wilson, Pease & Co. |

101 |

2.1 |

Sadler & Co. |

99 |

2.1 |

Raylton Dixson & Co. |

77 |

1.6 |

Normanby Iron Works |

77 |

1.6 |

Bell Brothers |

73 |

1.5 |

Clay Lane Iron Works |

34 |

0.7 |

Accident |

8 |

0.2 |

Others |

2,939 |

61.1 |

Total |

4,807 |

100.0 |

North Ormesby Hospital, Case Books, 1883–1888, 1885–1908, Teesside Archives, H/NOR10/2, 3

Hospital management

The North Ormesby Hospital was founded in 1859 as a Cottage Hospital from the deep concern of its founder, Sister Mary of the Christ Church Sisterhood, over the lack of nursing care for those injured by the boiler explosion in the previous year at the Ironworks of Snowden, Hopkins and Company in Middlesbrough. It is interesting to note that whilst the hospital retained its religious, philanthropic or charitable influences* G. Stout, History of North Ormesby Hospital (Redcar, 1989), pp.5, 48-85. throughout the period under review, shortly after its erection, as we have seen, it came to rely on the money raised by the workers of the iron & steel, and railway companies. With this point in mind, we would like to consider the internal organisation of the hospital and how it was run.

At the outset, the promoters of the hospital must have tried to remain neutral in regard to opposing interests, and diligently pursued their own aims to establish an independent medical institution. Thus, they not only organised a workers’ association named «The Working Men’s Committee» in the hospital for the purpose of obtaining workmen’s cooperation in aid of fundraising, but also asked the employers of the area to make an arrangement for their workmen to contribute a small amount of money to the hospital.* North Ormesby Hospital, Council Meeting Minutes Book, 1867-1907, Teesside Archives, H/NOR 1/1, 1st, July, 1868, 2nd Aug., 1871.

Moreover, the promoters called at the iron works themselves with the view to obtaining weekly contributions from the workers.* North Ormesby Hospital, Council Meeting Minutes Book, 1867-1907, Teesside Archives, H/NOR 1/1,27th Aug., 1867. They undoubtedly urged the ecclesiastical community of the area as well to contribute, setting up various schemes including medical charities of the Hospital Saturday and Sunday Funds.* Middlesbrough-On-Tees Medical Charities, Hospital Sunday March, 5th, 1872, pp.1-16.

Yet increasingly in terms of contributions to the fund-raising as well as of the number of patients admitted, this hospital came to function substantially as a worker’s medical centre to treat accidental cases which were of almost daily occurrence owing to the dangerous nature of the work they were engaged in. Immediately after its erection in 1859, and before the formation of the Hospital Council in 1866, workers employed by four of the major iron companies of this area, Cochrane, Bolckow & Vaughan, Samuelson, and Snowden, contributed 110 pounds sterling, which accounts for as much as 23 per cent of the hospital’s ordinary income.* Cottage Hospital Report for 1860, p.3.

From the hospital’s foundation, workers employed in these heavy industries took the initiative in establishing a system or organisation in the hospital for collecting subscriptions, as suggested by a remark in the Council Meeting Minutes Books. It was reported that a deputation of the Working Men’s Committee in the hospital ‘made some suggestions as to improved organisation for collecting subscriptions and for attending to other matters affecting the interests of the hospital’.* North Ormesby Hospital, Council Meeting Minutes Book, 1867-1907, Teesside Archives, H/NOR 1/1, 8th Oct., 1869. Then, a sub-committee was appointed to consider the subjects brought before the Council Meeting by the Workmen’s deputation, the result of which was a formation of the House Committee in 1870.* North Ormesby Hospital, Council Meeting Minutes Book, 1867-1907, Teesside Archives, H/NOR 1/1, 13th Nov., 1869.

It seems likely that the Working Men’s Committee in the hospital formed in 1867 ceased to be active in operation at the beginning of the 1870s after it had fulfilled its role of acting as trustees for enabling the working people in the area to form a close relationship to the hospital, and support it with substantial contributions.

The House Committee consisted of 20 to 36 individuals each representing the iron & steel, and ship-building, railway companies and chemical factories, as well as a friendly society. This Committee seems to have provided a better-organised structure than a provisional association of the Working Men’s Committee.* For the house committees in the voluntary hospitals, see V. Berridge, ‘Health and medicine’ in F.M.L. Thompson (ed.), The Cambridge Social History of Britain, 1750-1950, Vol.3, Social Agencies and Institutions (Cambridge, 1990), p.207. As for the House Committee of the North Ormesby Hospital, see B. Doyle, ‘Voluntary Hospitals in Edwardian Middlesbrough’, pp.13-20.

Meanwhile, the system of collecting workers’ contributions to the hospital fund-raising became more systematized and structured, with the share of the hospital’s ordinary income derived from workers’ contributions rising to more than 60 per cent, as we have already observed. The working class in the Middlesbrough area tended to regard this hospital as especially their own, and to give it their united and systematic support, presumably with the intent of using it as one of the most important safety-nets available. Hence the Council itself thought highly of the fact that the workers were assisting themselves and promoting self-help.* The Ninth Annual Report of the Cottage Hospital, North Ormesby, Middlesbrough, 1867, p.6. The Tenth Annual Report of the Cottage Hospital, North Ormesby, Middlesbrough, 1868, p.2.

Self help, patronage, or contributory insurance?

Contributions were likely to have been taken from the workers’ wages in each company, and in the earlier period, the Working Men’s Committee, or the Working Men’s Meeting formed in the hospital, seems to have made an arrangement for their contributions to be subscribed to the hospital. The evidence from the pay books of Bell Brothers, one of the major iron works of the area, shows that skilled, semi-skilled and un-skilled labourers as well employed by the company in the late 1860s, spent approximately 5 per cent of their weekly or fortnightly wages on providing against emergencies.* Bell Brothers, Clarence Iron Works, Pay Books, Vol.4, 1864-67, Coll Misc 0003, British Library of Political and Economic Science. For the sick clubs in Middlesbrough in the early nineteenth century, see Lady Bell, At the Works, A Study of a Manufacturing Town (Middlesbrough) (Newton Abbot, repr., 1969), pp.118-125. As regards the workers’ administration of the fund collected in the companies, see R. Fitzgerald, British Labour Management and Industrial Welfare 1846-1939 (London, 1988), p.86.

Bell Brothers made deductions from their workers’ wages for houserent, doctor’s fees contracted with the company, payments to sick club, and the ‘Roman Catholic Fund’. 2 pence in contributions to North Ormesby Hospital were taken from their fortnightly wages. Another 4 or 6 pence were deducted to pay for the doctor, together with 1 shilling and 4 pence for the sick fund.

It could be said from this evidence that sick benefit services in the period were independently organised at individual works.* For similar company-based sick benefit services, see for example, M.Seth-Smith, 200 Years of Richard Johnson & Nephew (Manchester, 1973), p.124, and R. Fitzgerald, British Labour Management, pp.84-92. The evidence would also seem to indicate that within companies, besides ordinary sick benevolent clubs organised for providing compensation during illness, or for paying for the doctor’s fees contracted with the firms, all of which were also financed with the contributions deducted from wages, there was a membership sick club especially designed for sending the injured to North Ormesby Hospital.

In times of sickness, scheme members could call upon this benevolent fund to which they each contributed only a minimal amount of money, say a farthing or a penny per week. If dependants of contributory scheme members needed hospital treatment, they could also apply to the fund. In the present state of our knowledge, the collecting system is not crystalclear. However, most likely, the contributory scheme members and their dependants could enjoy free treatment in the hospital in return for their weekly subscriptions deducted from their wages. Members might have had to obtain company doctors’ recommendations for hospitalisation.* For subscriptions and hospitalisation practices in the early twentieth century voluntary hospitals on contributory schemes, see S. Cherry, ‘Beyond National Health Insurance’, p.467.

Obviously there were other channels available in this period through which the working class could support themselves in times of hospitalisation, for example as is shown in Table 7. It illustrates how fund-raising and expenditure were undertaken in the Middlesbrough branches of the Amalgamated Society of Engineers and the Steam Engine Makers Society, with those for the hospital in the same year for comparison.* Amalgamated Society of Engineers, Yearly Report of Middlesbrough Branch, 1876, Modern Records Centre, University of Warwick, MSS 259/2/1/1. Annual Report of the Income and Expenditure of the Steam Engine Makers’ Society, 1876, p.198.

Unionised workers could expect fairly high proportions of the expenditures in medical care from their subscriptions, with as much as 29 per cent for the Steam Engine Makers Society and 9 per cent for the Amalgamated Society of Engineers. Yet especially for un-organised workers outside the formal associations such as trade unions, friendly societies, or other benevolent societies, the system relying on the medical care provided by a voluntary hospital of the area, would seem to have been an important self-supporting sick and accident fund based upon voluntarism.

Other iron and steel companies likewise must have supported a wide variety of welfare services for their workers. Company welfare was in the employers’ interests, especially in the iron and steel industry. Reliance upon export markets forced the iron & steel industry to be highly competitive and susceptible to trade cycles. Therefore, company-based or company specific labour management and industrial welfare were important to iron and steel companies.* Fitzgerald, British Labour Management, p.77.

Amalgamated Society of EngineersNo. of Branch members: 228 |

Steam Engine Makers Society No. of Branch Members: 15 |

North Ormesby Hospital |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

£ |

s. |

d. |

£ |

s. |

d. |

£ |

s. |

d. |

||||

Income | ||||||||||||

Contributions etc. |

515 |

11 |

8 |

Contributions etc. |

21 |

16 |

7 |

Subscriptions |

230 |

6 |

6 |

|

Received from |

Received from |

Subscriptions |

||||||||||

other branches |

110 |

0 |

0 |

other branches |

36 |

2 |

0 |

from Workmen |

646 |

15 |

11 |

|

Others |

36 |

3 |

3 |

Others |

3 |

9 |

7 |

Donations |

611 |

5 |

9 |

|

Total |

661 |

14 |

11 |

Total |

61 |

8 |

2 |

Total |

1,488 |

8 |

2 |

|

Balance Dec. 1875 |

1,269 |

18 |

5 |

Balance Dec. 1875 |

21 |

11 |

8 |

Balance Dec. 1875 |

426 |

8 |

4 |

|

Grand Total |

1,931 |

13 |

4 |

Grand Total |

82 |

19 |

10 |

Grand Total |

1,914 |

16 |

6 |

|

Expenditure | ||||||||||||

Travelling |

391 |

4 |

10 |

Travelling |

2 |

8 |

7,5 |

House-keeping Acc. |

1,477 |

14 |

11 |

|

Unemployed |

- |

- |

- |

Unemployed |

13 |

10 |

0 |

Medical & Surgical Acc. |

87 |

4 |

1 |

|

Sick |

169 |

5 |

4 |

Sick |

23 |

16 |

4 |

Furnishing & Repair Acc. |

89 |

14 |

||

Funerals |

12 |

0 |

0 |

Funerals |

5 |

0 |

0 |

Establishment Acc. |

284 |

5 |

0 |

|

Superannuation |

4 |

8 |

0 |

Superannuation |

- |

- |

- |

|||||

Others |

39 |

12 |

11 |

Others |

9 |

3 |

3,5 |

Others |

5 |

18 |

5 |

|

Total |

616 |

11 |

1 |

Total |

53 |

18 |

3 |

Total |

1,914 |

16 |

6 |

|

Balance, Dec. 1876 |

1,315 |

2 |

3 |

Balance, Dec. 1876 |

29 |

19 |

10 |

Balance, Dec. 1876 |

- |

- |

- |

|

Grand Total |

1,931 |

13 |

4 |

Grand Total |

82 |

19 |

10 |

Grand Total |

1,914 |

16 |

6 |

|

Amalgamated Society of Engineers, Yearly Report of Middlesbrough Branch, 1876, Modern Records Centre, University of Warwick, MSS 259/2/1/1. Annual Report of the Income and Expenditure of the Steam Engine Makers’ Society, 1876, p. 198.

Labour shortage or labour turnover was really a serious problem in a newly-built, isolated, industrial community exclusively dependent upon a staple industry of iron & steel and railways. As Professor Bob Fitzgerald has pointed out, in such a circumstance, employers tried to create an internal labour market within their firms, not only through improved security of employment but also by the provision of welfare benefits. In competitive industries such as iron and steel with small and medium-scale firms predominant, this tendency was more remarkable.* ibid., p.3.

In addition, a paternalistic attitude made sense, especially among the non-unionised labour in small and medium-sized businesses prevalent in the iron & steel industry during the period under review.* ibid., pp.84-7.

Apart from the company-based private welfare schemes which must have been rather unsystematic and less extensive at this stage, Middlesbrough’s own economic structure, that is, a newly-founded town whose economy was extremely concentrated on iron & steel and the railways, gave rise to a peculiar welfare system, as seen here. A mono-industrial structure, with most of the workers enduring almost similar working conditions, was likely to have brought about common interests among the workers. Thus the medical care which prevailed in the area during the period, provided by a voluntary hospital based on contributory schemes rather than on an old subscription-recommendation system, could be said to be a quasi-public means for social security.

Conclusion

In conclusion, let us consider the implications of the medical care provided by a British voluntary hospital in the late nineteenth century based on the case study of the early stage of a hospital system organised on nascent contributory schemes.

It is often suggested that Middlesbrough workers tended to be heavily involved in a range of self help organisations, such as friendly societies, trade unions or other benevolent societies, as for instance Professor Asa Briggs has noted.* A. Briggs, Victorian Cities, A brilliant and absorbing history of their development, Penguin Books edn.(Harmondsworth, 1990), p.246. The tendency seems to have resulted from the fact that it was an entirely new town, planted as late as 1830, and there were no fixed or disposable old endowments, available elsewhere, say, in London, Birmingham, Liverpool, Sheffield, Leeds or Glasgow, or other long-established towns. Thus Middlesbrough’s working class had to strive to cater for their own needs, which was likely to have strengthened, among the workers there, a grass-roots solidarity.* J. Turner, ‘The Frontier Revisited: Thrift and Fellowship in the New Industrial Town, c.1830-1914’ in A.J. Pollard (ed.), Middlesbrough, Town and Community 1830-1950 (Phoenix Mill, 1996), pp.98-9.

Strictly speaking, the system on which the management, finance and fund-raising of a voluntary hospital in this area were all based cannot be said to have originated from this working class grass-roots principle per se. As implied by a remark in the Council Meeting Minutes Books in 1867, iron companies would ‘issue notices to their workmen recommending them to contribute a farthing each man weekly to the hospital’.* North Ormesby Hospital, Council Meeting Minutes Book, 1867-1907, Teesside Archives, H/NOR 1/1, 27th Aug., 1867. Initially, workers seem to have been rather passive in that they just followed what the promoters of the hospital or the employers of companies in the area tried to set up in terms of managerial, financial, or fund-raising mechanisms of this medical institution.

Nevertheless, once the system was established, workers could identify this hospital as a medical institution promoting their aims; hence they participated actively, as they seem to have welcomed this contributory scheme which allowed for a certain-degree of grass-roots participatory democracy and encouraged a working-class tradition of self-help as Jose Harris has mentioned. * Cf. J. Harris, ‘‘Did British workers want the welfare State?’, p.200. As regards the initiatives taken by workers in other industrial areas, see P. Weindling, ‘Linking Self Help and Medical Science: The Social History of Occupational Health’ in P. Weindling (ed.), The Social History of Occupational Health (London, 1985), p.17. They tended to have regarded this hospital as particularly their own, designed to promote their self-help. Thus they continued to give this institution their united and systematic support to make it a reliable safety-net. The existence of this sort of medical institution in their vicinity could lessen the fear arising from severe industrial accidents due to the hazardous physical environment.

On the other hand, the maintenance and promotion of such a medical institution like the voluntary hospital as seen in this area, which virtually specialised in treating industrial accidents and emergency cases, seemed to have had tangible advantages for the employers, as a means of meeting the needs of their workforces, upon which efficient production depended. Thus, the origin of the medical welfare system in this area was a mixture of indirect company involvement and the encouragement of working-class self-help.

It consisted of the co-existence of the so-called ‘mixed economy’ of medical service provision with a charitable principle on the one hand, and a sort of contributory quasi-insurance arrangement, supported both by industrial and labour concerns on the other hand.* See S. Cherry, Medical services and the hospitals in Britain, 1860-1939, p.72. In this sense, what we have been seeing in this system was a composite of different factors, that is to say, self-help promoted among the working population, patronage or paternalism of management towards their workers together with the intention of securing a robust and efficient labour force, and an early form of contributory insurance.

References and notes

See for example, S. Cherry, Medical services and the hospitals in Britain, 1860–1939 (Cambridge, 1996), pp.30, 41–53.

P. Johnson, ‘Risk, redistribution and social welfare in Britain from the poor law to Beveridge’, in M. Daunton (ed.), Charity, self-interests and welfare in the English past (London, 1996), 225–248, p.246.

J. Harris, ‘Did British workers want the welfare state? G.D.H. Cole’s Survey of 1942’ in J. Winter (ed.) The Working Class in Modern British History (Cambridge, 1983), 200–14, pp.210–11.

B. M. Doyle, ‘Voluntary Hospitals in Edwardian Middlesbrough: A Preliminary Report’, North East History, 34 (2001), 5–33, p.9.

North Ormesby Hospital, Council Meeting Minutes Book, 1867–1907, Teesside Archives, H/NOR 1/1.

North Ormesby Hospital, Case Book, 1861–1870, Teesside Archives, H/NOR 10/1.

North Ormesby Hospital, Case Books, 1883–1888, 1885–1908, Teesside Archives, H/NOR 10/2, 3.

North Ormesby Hospital, The First to Fifty Ninth Report of the Cottage Hospital, North Ormesby, Middlesbrough, 1859–1917.

Calculated from North Ormesby Hospital, Case Book, 1861–1870, Teesside Archives, H/NOR 10/1, and Case Books, 1883–1888, 1885–1908, Teesside Archives, H/NOR 10/2, 3.

Calculated from North Ormesby Hospital, The First to Fifty Ninth Report of the Cottage Hospital, North Ormesby, Middlesbrough, 1859–1917.

Males aged 0–4 comprise 8.9 per cent , with females of the same age group occupying 11.3 per cent of the total of 10,068 male, and 4,807 female in-patients.

Based on the record linkage work of the census enumerators’ books, 1851–61, 1861–71 and 1871–81, HO 107/2383, RG 9/3685–3689, RG 10/4893, RG 11/4851, Public Record Office. As for the development of the iron and steel industries in Middlesbrough during the period, see for example, A. Birch, The Economic History of the British Iron and Steel Industry 1784–1879, (London, 1967), p. 333. I. Bullock, ‘The Origins of Economic Growth on Teesside 1851–81’, Northern History, 9 (1974), pp. 85–96. W. Lillie, The History of Middlesbrough, an Illustration of the Evolution of English Industry (Middlesbrough, 1968), pp. 96–109. D. Taylor, ‘The Infant Hercules and the Augean Stables: A Century of Economic and Social Development in Middlesbrough, c.1840–1939’ in A.J. Pollard (ed.), Middlesbrough, Town and Community 1830–1950 (Phoenix Mill, 1996), pp.53–80.

The Eighth Annual Report of the Cottage Hospital, North Ormesby, Midlesbrough, p.3.

See S. Cherry, ‘Beyond National Health Insurance. The Voluntary Hospitals and Hospital Contributory Schemes: A Regional Study’, Social History of Medicine, 5, 4(1992), 455–82, p.480.

For the national average of length of stay in voluntary hospitals during the period, see R. Pinker, English Hospital Statistics 1861–1938 (London, 1964), p.111.

For example, Annual Report of the Cottage Hospital, Middlesbrough, 1862, p.2.

Calculated from North Ormesby Hospital, The First to Fifty Ninth Report of the Cottage Hospital, North Ormesby, Middlesbrough, 1859–1917.

Hospital mortality in the General Infirmary at Leeds has been calculated from Admission and Discharge Registers of the General Infirmary of Leeds, 1815–17, Leeds District Archives, Sheepscar Library. Causes of death and hospital mortality in North Ormesby Hospital have been calculated from North Ormesby Hospital, Case Book, 1861–1870, 1883–1888, 1885–1908, and The First to Fifty Ninth Report of the Cottage Hospital, North Ormesby, Middlesbrough, 1859–1917.

Calculated from North Ormesby Hospital, The First to Fifty Ninth Report of the Cottage Hospital, North Ormesby, Middlesbrough, 1859–1917.

For the fund-raising of the hospital in the twentieth century, see R. Lewis, R. Nixon, and B. Doyle, Health Services in Middlesbrough: North Ormesby Hospital 1900–1948, Centre for Local Historical Research, University of Teesside (Middlesbrough, 1999), pp.9–16. B. Doyle and R. Nixon, ‘Voluntary Hospital Finance in North-East England: The Case of North Ormesby Hospital, Middlesbrough, 1900–1947’, Cleveland History, 80 (2001), 5–19, pp.8–14.

S. Cherry, ‘Before the National Health Services: financing the voluntary hospitals, 1900–1939’, Economic History Review, 50 2(1997), 305–326, pp.318, 324.

For the workmen’s contributions in selected London and provincial voluntary hospitals, see Pinker, Statistics, pp.152–4.

The Eighteenth Annual Report of the Cottage Hospital, North Ormesby, Middlesbrough, 1876, pp.10–13, The Annual Report of the State of the General Infirmary, at Leeds, from September 29th, 1856, to September29th, 1857.

For the urban morbidity and the fund-raising of the General Infirmary at Leeds at the beginning of the nineteenth century, see M.Yasumoto, Industrialisation, Urbanisation, and Demographic Change in England (Nagoya,1994), pp.113–156.

The Cottage Hospital Report for 1860, p.3.

Calculated from North Ormesby Hospital, The First to Fifty Ninth Report of the Cottage Hospital, North Ormesby, Middlesbrough, , 1860–1881.

Calculated from North Ormesby Hospital, Case Book, 1861–1870.

Calculated from North Ormesby Hospital, Case Books, 1883–1888, 1885–1908.

The Fifteenth Annual Report of the Cottage Hospital, North Ormesby, Middlesbrough, 1873, p.7

North Ormesby Hospital, Council Meeting Minutes Book, 1867–1907, Teesside Archives, H/NOR 1/1, Oct. 8, 1879.

As regards the employers’ contributions to the voluntary hospitals based on contributory schemes in East Anglia in the early twentieth century, see S. Cherry, ‘Beyond National Health Insurance’, pp.478–9.

G. Stout, History of North Ormesby Hospital (Redcar, 1989), pp.5, 48–85.

North Ormesby Hospital, Council Meeting Minutes Book, 1867–1907, Teesside Archives, H/NOR 1/1, 1st, July, 1868, 2nd Aug., 1871.

North Ormesby Hospital, Council Meeting Minutes Book, 1867–1907, Teesside Archives, H/NOR 1/1,27th Aug., 1867.

Middlesbrough-On-Tees Medical Charities, Hospital Sunday March, 5th, 1872, pp.1–16.

Cottage Hospital Report for 1860, p.3.

North Ormesby Hospital, Council Meeting Minutes Book, 1867–1907, Teesside Archives, H/NOR 1/1, 8th Oct., 1869.

North Ormesby Hospital, Council Meeting Minutes Book, 1867–1907, Teesside Archives, H/NOR 1/1, 13th Nov., 1869.

For the house committees in the voluntary hospitals, see V. Berridge, ‘Health and medicine’ in F.M.L. Thompson (ed.), The Cambridge Social History of Britain, 1750–1950, Vol.3, Social Agencies and Institutions (Cambridge, 1990), p.207. As for the House Committee of the North Ormesby Hospital, see B. Doyle, ‘Voluntary Hospitals in Edwardian Middlesbrough’, pp.13–20.

The Ninth Annual Report of the Cottage Hospital, North Ormesby, Middlesbrough, 1867, p.6. The Tenth Annual Report of the Cottage Hospital, North Ormesby, Middlesbrough, 1868, p.2.

Bell Brothers, Clarence Iron Works, Pay Books, Vol.4, 1864–67, Coll Misc 0003, British Library of Political and Economic Science. For the sick clubs in Middlesbrough in the early nineteenth century, see Lady Bell, At the Works, A Study of a Manufacturing Town (Middlesbrough) (Newton Abbot, repr., 1969), pp.118–125. As regards the workers’ administration of the fund collected in the companies, see R. Fitzgerald, British Labour Management and Industrial Welfare 1846–1939 (London, 1988), p.86.

For similar company-based sick benefit services, see for example, M.Seth-Smith, 200 Years of Richard Johnson & Nephew (Manchester, 1973), p.124, and R. Fitzgerald, British Labour Management, pp.84–92.

For subscriptions and hospitalisation practices in the early twentieth century voluntary hospitals on contributory schemes, see S. Cherry, ‘Beyond National Health Insurance’, p.467.

Amalgamated Society of Engineers, Yearly Report of Middlesbrough Branch, 1876, Modern Records Centre, University of Warwick, MSS 259/2/1/1. Annual Report of the Income and Expenditure of the Steam Engine Makers’ Society, 1876, p.198.

Fitzgerald, British Labour Management, p.77.

ibid., p.3.

ibid., pp.84–7.

A. Briggs, Victorian Cities, A brilliant and absorbing history of their development, Penguin Books edn.(Harmondsworth, 1990), p.246.

J. Turner, ‘The Frontier Revisited: Thrift and Fellowship in the New Industrial Town, c.1830–1914’ in A.J. Pollard (ed.), Middlesbrough, Town and Community 1830–1950 (Phoenix Mill, 1996), pp.98–9.

North Ormesby Hospital, Council Meeting Minutes Book, 1867–1907, Teesside Archives, H/NOR 1/1, 27th Aug., 1867.

Cf. J. Harris, ‘‘Did British workers want the welfare State?’, p.200. As regards the initiatives taken by workers in other industrial areas, see P. Weindling, ‘Linking Self Help and Medical Science: The Social History of Occupational Health’ in P. Weindling (ed.), The Social History of Occupational Health (London, 1985), p.17.

See S. Cherry, Medical services and the hospitals in Britain, 1860–1939, p.72.

KEYWORDS: accidental and emergency cases, voluntary hospital, contributory schemes, workers’ contributions, iron and steel industries, railways, self help, patronage, safety nets, contributory insurance.

Professor

Faculty of Economics

Komazawa University

1–23–1 Komazawa

Setagaya-ku

Tokyo

Japan 154–8525

Phone: 03–3418–9369 (direct)

yasumoto@komazawa-u.ac.jp