Supervising foreign students in Latvia

The Norwegian outplacement system

When the first group of Norwegian medical students heading for their mandatory practice period landed in the Riga airport with the SAS flight from Stockholm on a September day in 1995, marked the end of a long dispute at the Faculty of Medicine in Oslo. Since 1968, family medicine had been a growing discipline in the Faculty, a reflection of the increasing political weight placed on primary health care, as opposed to the tendency of leaning towards specialist care – as experienced in the first post war period. This emphasis in family medicine was further enforced when a new curriculum with radical changes was prepared in the early nineties and finally introduced in 1996.

For some time, students having their family medicine and public health term at the University of Oslo had been placed with general practitioners for a period of four weeks as part of their training. In the Institute of General Practice and Community Medicine was a section working with medical anthropology, running many projects abroad. The staff members there had colleagues in far flung places such as South Africa, Botswana and Palestine. Some students had been allowed to spend their practice periods in such exotic places rather than in Norway, and the experiences were good. The students learnt a lot and got new perspectives on Norwegian medicine. Therefore, the idea came up to deploy students to other countries for similar reasons. As Øivind Larsen had contacts in Latvia, the idea was at hand to set up an outplacement system also there, later supplemented by a parallel outplacement in La Crosse, Wisconsin, USA.

It should not, however, be concealed that this sending out of students to foreign countries met strong opposition on the local level in Oslo, in spite of the fact that the students themselves were very enthusiastic. When finances tightened in Oslo around the turn of the century, the students going abroad had to pay the lion’s share of the expenses out of their own pockets. And they willingly did so out of curiosity and personal interest. They had no remuneration from the University, as their mates did, when they had their practice weeks in Norway.

However, even then there was local resistance. And this resistance came from the Faculty and from the teachers in general practice, who insisted that the outplacement system was meant to teach the students Norwegian primary health care, not something else. They should not be diverted from this primary goal.

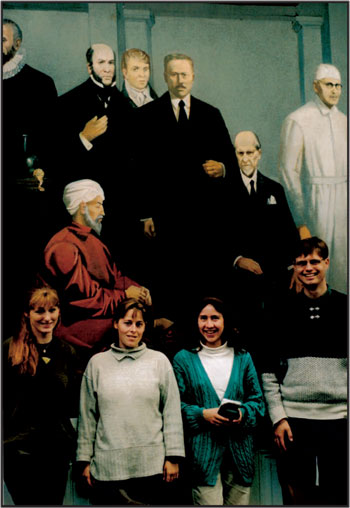

Norwegian medical students in front of a wall painting of heroes from the history of medicine in the Medical Museum of Riga 1996.

However, interested teachers succeeded in setting up tempting timetables for the student-stays abroad, and the enthusiasm on the local level, e.g. in Latvia, matched the high motivation of the students. Yet when the outplacement system to Latvia came to an end in 2001 for different reasons (including the fact that the situation in Latvia became more and more like that of Norway), «internationalisation» suddenly became the buzz word at the Medical Faculty in Oslo. From now on student stays abroad were simply encouraged, but that was too late for the setup used in Latvia.

The importance of the high motivation of the Oslo students was contrasted when one group was supplemented with four students from the NTNU – the University of Trondheim. They had got the impression, before arriving in Riga, that they had been whisked away to a foreign country because their home faculty had not managed to fix the outplacement arrangement which they were entitled to in Norway. Thus their motivation was different, and this probably had considerable influence on the outcome of their stay.

Encounters with the strange

In Latvia, the students encountered a different study situation, living closely together with their comrades for four weeks in a country which for almost the entire period 1995–2001 was perceived as quite different from Norway. They encountered Riga, a city with much to see – and with possibilities for partying and night life that were quite different from in Oslo, not least because of the comparatively low price level.

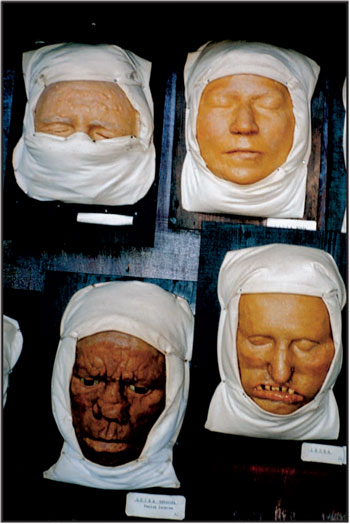

But they also encountered the medical problems they were expected to address, and they often encountered them on another and more serious level of disease progression than they would have done in Norway. At least in the first years, the geographical and social transfer from Norway to Latvia also implied a transfer into another period of medical and social history, because many parts of what they saw of diseases and health care services were on another stage of development than in Norway. They were on board a time machine. Examples included the encounters with infectious diseases like leprosy, tick borne encephalitis, diphtheria and tuberculosis. Visits to Soviet style psychiatric wards also made lasting impressions on them.

The same was even experienced by many seasoned doctors from Norway, coming over to Latvia and for example visiting the leprosy hospital at Talsi.

In some cases, practices were also surprisingly different to Norway: We immediately felt that a wrong question had been posed when we expressed astonishment at meeting a cat in a Riga surgical ward. The answer was given with raised eyebrows. The cat was there to get rid of mice and rats, of course!

Exhibition of reports from the Latvia/USA student venture, on display in Domus Medica at the University of Oslo (2004).

During the intensive eighteen day teaching programme in Latvia, each group of students was exposed to topics ranging from the emerging general practice culture, topics from nutritional and occupational hygiene, in addition to taking part in excursions and study visits related to the report they were expected to write when back in Oslo. «Imagine that you are members of a study group who must report to the World Health Organisation on a certain medical problem, and relate it to the corresponding conditions in Norway (later also in the United States)», were the instructions they received when sent off for their stay. * As can be seen from the attached list of reports, a wide range of topics were treated. See also Kilkuts & al. 2004.

For the students this was also training in a new way to observe, to extract and evaluate information and to make notes for a report. For their teachers this was an interesting process to supervise.

The fact that public health and community medicine in Latvia are not as integral parts of the medical care as in Norway, became obvious during the practice periods of the Norwegian students, so perhaps there was also some feedback to Latvia through the Norwegian teaching process.

Insights in Latvian rural health services were conveyed by means of excursions. Here the local, later closed, hospital in Madliena in Ogre county. For some years in the 1990ies a Norwegian mother-and-child clinic had its premises on the first floor, run by Dr. Øivind Juris Kanavin together with the midwife Annemette E. Riisgaard.

Madliena paediatric ward 1996.

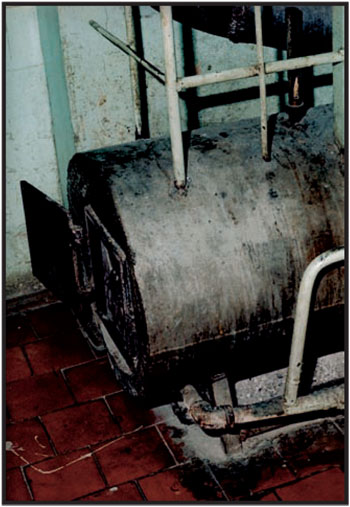

Madliena hospital hotwater heater 1996.

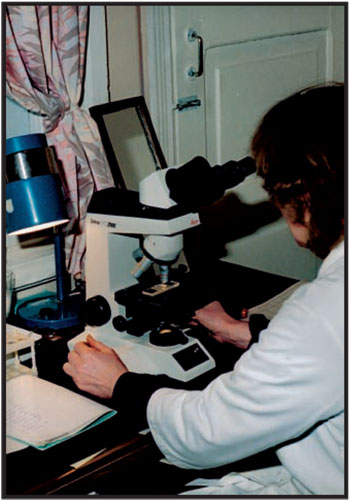

Madliena contrast: A high-end microscope for diagnostics 1996.

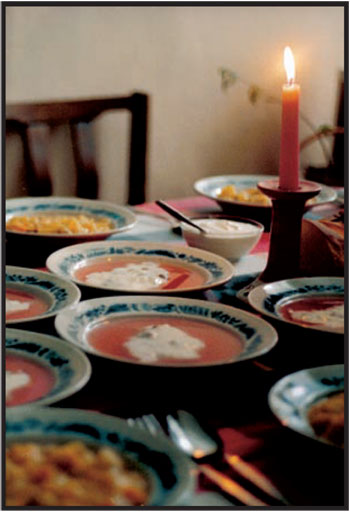

Madliena hospital dinner 1996.

Madliena old folks home 1996.

Leprosy is not history in Latvia. Moulages from the leprosy hospital in Talsi, west of Riga 2000.

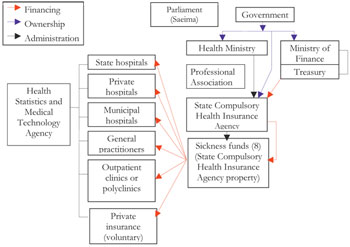

Organizational structure of health care system 2003

(Since 1991 several attempts of reforming the health care system were made. Lack of commitment and political will led to half-hearted solutions, and new structures and organisational models appeared. How the health care system has looked like, has varied with which year the question refers to. This is an example from 2003.)

Hospital «Linezers», beautifully situated and discreetly set back in a forest-like park with pines and rhododendrons outside Riga, open to the public now, without the gates and guards of olden times (Photo 2005).

Modern Riga at night (2005).

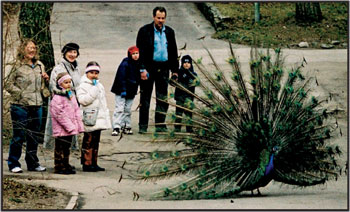

Peeping at the peacock in Riga Zoo (2005).

Gastronomic affluence in postmodern Riga: The «Lido» restaurant concept (2005).

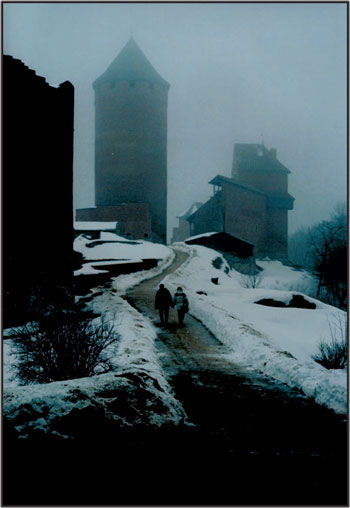

A scent of Latvian middle ages. (Sigulda 1997).

and