Sources, interpretation and implementation

Dangerous lenses

– The photographs have to be printed in full colour!

My friend and co-author was quite clear and left no doubt behind his statement. We were having one of our meetings revising manuscripts and looking through material to be presented in the book you have in your hands right now.

– Are you quite sure? I carefully objected. This is no tourist guide or travel agency pamphlet; we are intending to illustrate quite serious things, a social development. And then the black-and-white abstraction renders more emphasis on our points, I said. Duotone black-and-white where deep blacks contrast whitish highlights and promote our messages, I argued and mentioned examples from other books. The social issue is better displayed by means of a monochrome presentation, I persisted.

– Just therefore, the pictures should be in colour! Because the Latvian world has not been black and white in the period we describe! Even in the most difficult periods there have been happy Latvians. The quality of life is dependant on a series of factors, not least on the expectations. An old saying tells that happiness is to make joy simple. Playing children or young couples strolling between blossoming trees in the beautiful parks of Riga* These parks are indeed interesting, see Klavina 2002. may enjoy themselves irrespective of hardships of life. Perhaps such qualities of life rank even higher when life is harsh. A black-and-white presentation does not credit reality; it even may tilt towards social pornography!

Sources and methods

Our discussion about photographs in fact had wider perspectives than the printing issue. We were touching on the methodological basics in describing a situation by means of different sources covering the same situation; in other words we had arrived at the essence of historiographic methodology* See any textbook of historical methodology. Here is used the logics of the survey article by Larsen 1968.. interpretation of the collection of sources you have found: What do they really tell in light of each other, in light of your previous knowledge, and in light of the hypothesis you have for your study? The fourth and final step is the writing or communication of a story in a way which yields justice to the situation itself, to the sources and to all the steps preceding your presentation. Sources may be ranked based on their proximity to the object of study, from remains of the object (primary sources) to descriptions which are based on that seen through the eyes of others (secondary sources). Anyhow, the use and assessment of sources, irrespective of their nature, will depend on the context in which they belong, to the context when used and on the presumptions and theoretical framework held by the observer. When the context is complicated, and when substantial cultural differences may be presumed to exist between the observer and the object under observation, the interpretation issue becomes particularly crucial. And even if there should be no difference, such difficulties, as a rule, come more clearly to sight when dealing with contemporary history. All precautions and objections become especially visible. And Latvia from 1991 and up to today is contemporary history.

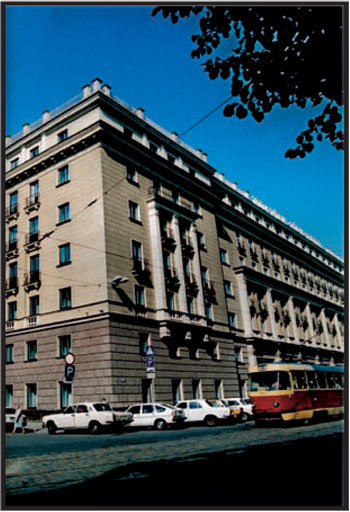

Soviet style Riga (1995).

Posh Riga (Hotel Riga opposite Opera House, 1993.)

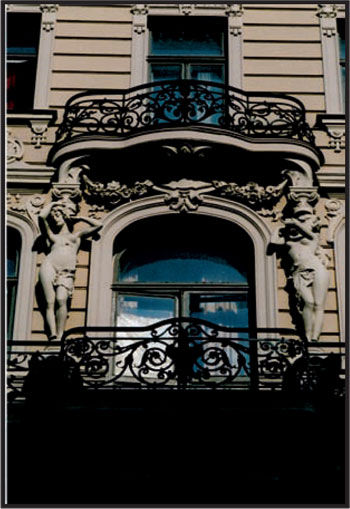

Art noveau Riga (in Albert Street).

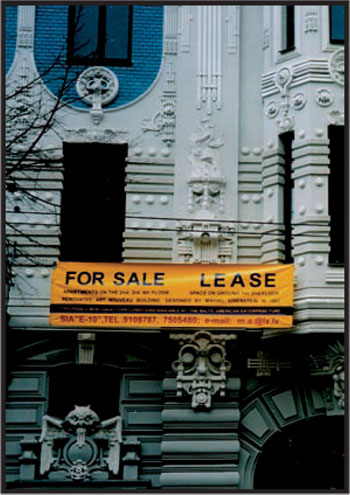

Heritage for sale (2001), Mikhail Eisenstein’ Riga. House in Elisabeth Street, built by the famous architect.

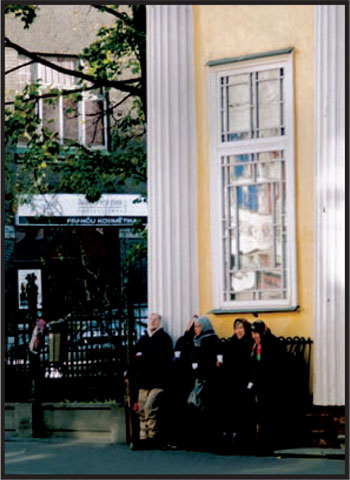

Begging women’s Riga (in the Street of Freedom, 2003).

Photographs as sources

In general, photographs are sources of a description of a situation, just like an oral statement, a text or a relic, and they have to be subject to just the same methodological considerations as any source. However, pictures and other visual sources carry a specific characteristic: They are more directly accessible to the spectator, are perceived by means of a wider range of senses and engage emotions* The classical work “On photography” by Susan Sontag elaborates this reasoning.. But in fact, it is not the picture, as such, which has these characteristics, the picture is only a conveyor of what you see, of your observation. Strictly, we are dealing with methodological issues linked to the use of observations as sources, represented by a picture which combines the object (the source) with the interpretation of the observer (the photographer, the publisher and others involved).

Therefore, the use of pictures as sources may be a powerful tool and even a dangerous one! Some examples of this include a very interesting series of high quality photographs of wounded soldiers from the American Civil War in the 1860s, taken on the orders of the Surgeon General* Larsen 1991.. In their simplicity they demonstrate the cruelty of war in a way quite different from often romanticised pieces of art of the time. When presented today, they portray the wartime stories from the North and the South in another light, and one may only counterfactually consider their impact if they had been widespread at the time they were made.

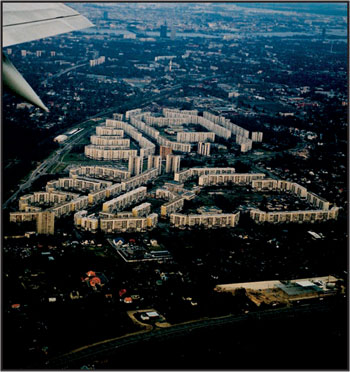

The Latvia of the Latvians. Densely populated dwelling areas devoid of «offsite» and «onsite» «markers», places where tourists seldom venture, even if they pretend to profess an intention to get to know the country (Southwest of Riga 2005).

Through the First World War (1914–1918) and especially during the Second World War (1939–1945) photography developed from a method of documentation into a weapon cleverly manipulated by the engaged parties into propaganda and influencing of minds. And further on, especially following the general introduction of television, photography became a major factor in setting the political scene. The grave of an unknown photographer, in fact, deserves to be paid same respect as the traditional grave of the Unknown Soldier.

The ever growing visualization of information gives the picture an increasing weight as a source, in comparison with other forms of evidence. Events escaping photography may seem to have never happened, whilst events in pictures or on television screens spark reaction. But from the methodological point of view: Who and what guide the eyes of the photographer?

This development makes the selection and presentation of visual material increasingly difficult. And our study from Latvia is no exception. One of the reasons for the complexity might be illustrated by the «marker» principles* See above, and MacCannel 1989. used in tourism theory: The tourist sees and takes photographs of what he or she are expected to see and take photographs of. Your mission is completed when you take home the pictures you are expected to take home. Europeans often joke about Japanese tourists who take snapshots of themselves in a hurry in front of an attraction. Then they rush back in their bus and are content. The next attraction is waiting.

But it is my point that the same is done by the media and other agents who in summary make up the general picture of the world around us and much of the historical source material left behind. Some examples could be mentioned: Has a successful photojournalist ever visited Cuba without returning with a bunch of photos of whores in windows? When in Africa, the compliant journalist takes pictures of starving children with swollen bellies; that is often what is demanded by his boss back home. Such photographs attain an iconic status. That some African children are nicely dressed and taken to kindergartens and schools like in Europe or in the US, does not have the same thrill and may even be politically incorrect to present. Even in heavily suffering Africa there are happy Africans, just as in Latvia. That is also part of history.

The discussions held between my co-author and myself and the literature covering these methodological subjects were not a mere academic exercise, because selection and interpretation of pictures describe a reality which in turn

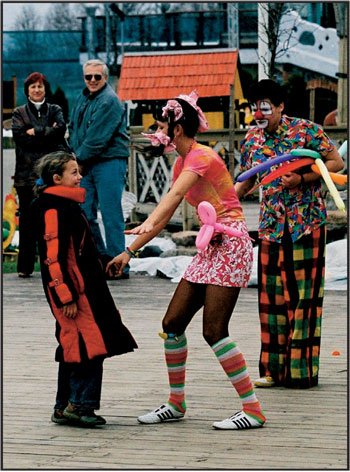

Entertainment 2005: The playing clown.

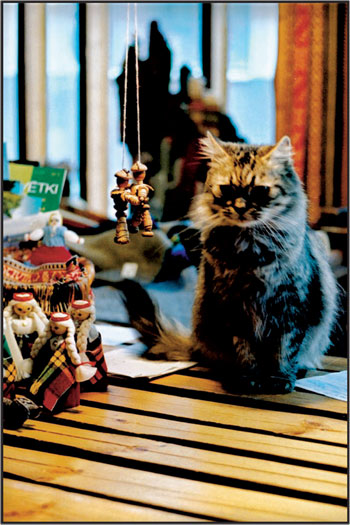

Cat guarding merchandise in a Valnu Street handicraft shop (2000).

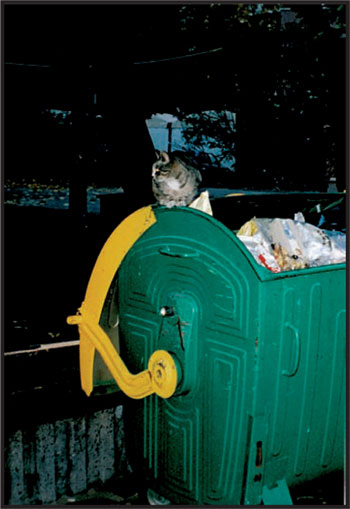

Cat guarding garbage (2000).

Cat off duty on a Lada (1995).

Cats guarding cars (2000).

A photographer with special interests, or perhaps with an agenda, may skew the impression he leaves. A blunt example here illustrates the meaning and allows for generalization:

Is Riga a special ecosystem for cats?

Ethics of the eye

Photographs piled up on our desks. Out of hundreds covering more than a decade a selection had to be made. When it comes to health and social conditions, however, a selection has already been made before any camera shutter button has been pressed down. There are some tacit rules indicating when to raise a camera and when not to do so. There are private spheres which should remain so. Pictures of patients or of deplorable living conditions may comply with the truth and make up an important part of the public health reality, but they are either never taken, or if so never presented for ethical reasons. Photographic evidence of health and living conditions as a rule are inherently skewed. And when photography is permitted or even encouraged, it might be that what the eye sees is not representative, or the situation may even have been staged just for you to photograph? As part of an agenda?

– Be aware of sights that are meant just for you and your fellow photographers, my co-author has warned me several times; though not, of course, telling me anything new, as this fact becomes more and more obvious the more experienced you are with the camera. Are people carrying billboards in the streets of Riga with slogans from both sides of the Latvian-Russian tension, representative of the existence and extent of a conflict, or are they meant to give clues to those who want to maintain and nurture a state of unrest? An example reproduced here (page 118) is a board where the message conveyed even was differently tailored to the English and the Russian readers!

Sights to see

During the years of transition, the visual impression of Latvia has changed profoundly. We have already touched on it, and the pictures prove it: City life, people, clothing, etc. look different, signs of what Westerners usually perceive as prosperity and diversity pop up, and advertisements, commercials on TV etc. have been westernised. However, this shift to the utterances of a different culture should not be mixed up with shifts in life and health conditions, at least not without further reflection.

Modern urbanism in the Western world has developed certain traits and ideals over time that are now also found in Latvia, visible in positive and negative ways. But what do these signs mean as markers for the society in the wider perspective?

Let us select one example: Beggars in the streets. The presence of beggars may signal poverty and social despair. The sight is a need for charity, awakening the sociologist’s interest in charity as a principle of caretaking, having been dominant in many social settings, and now perhaps being reintroduced as a major factor in capitalist care. On the other hand, at least in Western welfare societies, beggars in the streets are more and more accepted as part of a cultural diversity, an attitude which normalizes begging behaviour. Begging shifts towards a means of earning money. Begging becomes part of economic redistribution in society, to put it bluntly, just as criminality does if only gently punished. In 18th century England one risked to be hanged for a minor burglary* Commented on already in 1826 by the Norwegian hygeinist Frederik Holst., in Moslem countries you risk to get your hand chopped off even today, but in many Western countries police do not bother too much about robberies. Cultural changes take place all the time. Therefore, a picture of something such as beggars may be ambiguous.

There are also other connotations. In some countries drug abuse is a major problem, and begging may be one of the ways to fund a drug habit. The sight of a beggar may then evoke other associations than when begging is an expression of general poverty. The picture of a beggar needs a context in which to be interpreted correctly, and so it is down the whole line of objects you might take photographs of.

As we talked about the selection of photographs, my co-author said: – I could tell another story than you do about virtually every one of your pictures!

Riga street 1997.

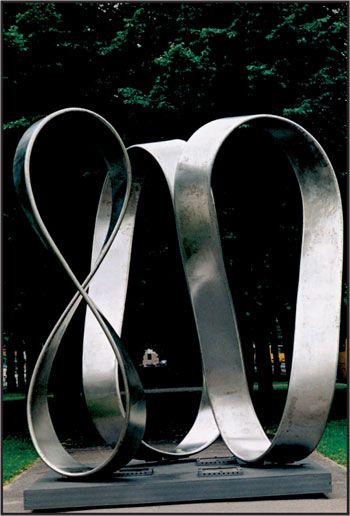

Riga celebrated eight hundred years of history in 2001. But what does that mean? A question should be raised if this has been a continuous history or a series of consequent histories following each other. (Sculpture photographed 2002).

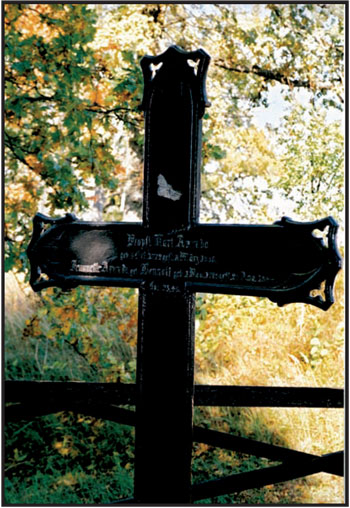

German time Latvia: German grave from the 19th century (Photo 2002).

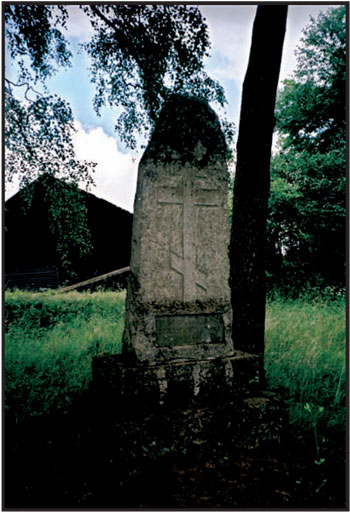

Russian time Latvia: Kekava tombstone (Photo 2002).

The medical museum in Riga with its vast collections, is a lasting proof of how Latvia was internalised within the Soviet Union, as national historical treasures are found here. This photograph shows the original report written upon the autopsy of Lenin (Photo 1998).

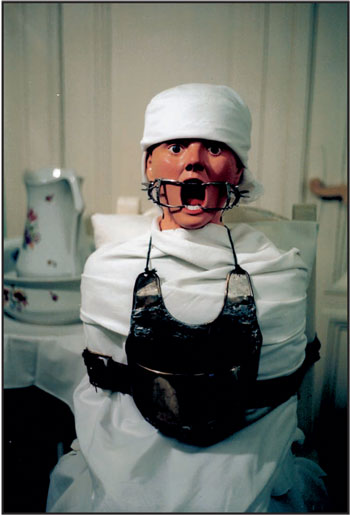

Doll for demonstration of how to prepare a patient for tonsillectomy, displayed in the Riga museum of medical history (2000).

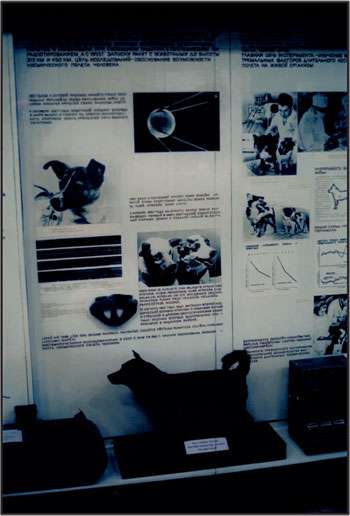

Top science in the museum, the climax for school classes, for endless rows of student groups from health professions and for tourists to see the supremacy of Soviet medicine: The dog Laika who had been in space! (Photo 1997).

History conveyed by means of paintings in the medical museum, here an example from hygiene (Photo 1994).

An inter-war «glass lady» in the Riga Anatomy museum (1998).

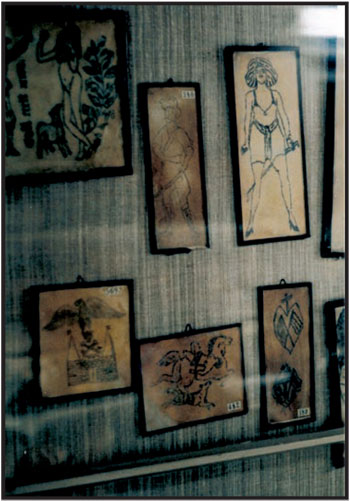

Riga Anatomy museum: Preserved sailors’ tattoos (1998).

The effect of sights

In the years since independence, news from the Baltic countries has been flooding westwards, a strong contrast to the preceding years, when some occasional political brochures from exiled Balts were often the only messages available to hear.

Up to the end of the 1980s it was not uncommon that people in Scandinavia mixed up the Baltic States. What was Estonia, what was Latvia and where was Lithuania? The countries belonged to another world, and apart from that, was it not all part of the Soviet Union? Behind the Iron Curtain? It is a historical research topic in itself to assess the impact of the previous scarcity of information, on the approaches from the West when the curtain was lifted. And how representative was the breaking news coverage about the liberation process? The internal and external picture which was painted, how did it influence the development before and after 1991?

This general picture after independence became the basis for attracting investors who were of benefit to the Baltic countries, but also for exploiters seeing potential opportunities.

Just one point which connects to health and health conditions: Social misery is always popular in Western media. People coping with their daily life but mastering it does not have the same appeal. I wonder what effect the misery trend in the Western media has had on the contacts between the Baltic States and its neighbours regarding relief efforts. The misery trend creates misery expectations. However, the notion of misery is diverse: It may be objective misery as can be observed and described through hard facts. But we have also to deal with perceived misery, which is not necessarily the same. In fact, mastering misery may contain an element of pride which is an asset. Dear reader, allow me to tell you about three personal experiences:

The first one took place on an autumn day of 1944 in wartime Oslo. I was six years old and attended first grade in school. It is possible that wartime kids are more reflective than children are under normal circumstances, because I recall what happened very clearly: A couple of nicely dressed ladies, I still remember their fur coats, entered our classroom. They brought boxes with second hand clothing in them, and items were handed out one by one as gifts. One pupil got a cap, another a sweater etc., and everybody had to bow nicely and pay humble thanks.

I remember that I disliked the situation intensely. I was very well aware that my parents worked hard to provide necessities in a time when almost nothing was available, and what would my mother say to this charity when I came home from school? When my turn came and a pair of trousers was presented to me, I remember that I politely declined and said that my parents cared for me. However, perhaps I also pointed out what was obvious for all to see – they were girls trousers. I was too young to have heard the old Roman proverb noli dentes equi donati inspicere, never check the teeth of a horse which is given to you as a present.

The reaction from the school was remarkable. I was simply expelled from school by our teacher, because of my deviant behaviour, but I was, in short, taken in again into another class. However, I still maintain that I did right the right there, I perceived the charity as an offensive and an assault on my pride of belonging to a family which I felt – correctly or not – coped with the difficult situation.

The other experience stretches over the recent years when I have been engaged in the Baltics. In Norway, second hand clothing and other overspill from our affluent society are still collected and shipped eastwards, provoked by media»misery-reports», but now donated to Baltic States which are developed members of the European Union. How representative are such reports, and what are the chances of humiliating decent people? Of course it may be acceptable sometimes to get something for free, but the social impact of charity on a modern population needs to be studied. Well-meant, but perhaps a little bit misdirected relief is nowadays initiated because of unbalanced media coverage, where the pictures play an important part.

My third relevant experience took place on board a Riga-bound flight from Stockholm in the early nineties. My fellow passenger, a young Swedish businessman shortened the fifty minute flight and displayed his importance by piling up and inspecting lots of documents in his lap, seemingly faxes, invoices and contracts. As one of the sheets passed the front of my nose, I simply could not avoid reading the message from the East: Please do not send more merchandise of that (probably low) quality!

In conclusion, I think that experiences from the Baltics in the transition period should give important clues with general relevance for setting up mutual contacts and relief work. Relief should be related to the real needs of the recipient, be based on an inside perspective and not just comply with assumptions, agendas and needs on the side of the provider.

And on the other hand: All things have two sides. It should not be forgotten that something also happened the other way round. The West became an arena for Baltic initiatives.

Myths, stereotypes, presumptions and the use of sources

Myths are sayings linked to something, such as a place, without requiring evidence, and they exist in spite of that. Examples: People from X are stupid, people from Y are industrious and people from Z should be praised for their cleanliness. If examined more closely, probably neither the stupidity of people from X is more widespread nor the cleverness in Y or the hygiene in Z. But myths are present, and the less acquainted people are with each other, the more they persist.

Stereotypes are worse, because they often base on a sort of arithmetic mean and cannot be rejected so easily. An example: «Norwegians are rich». This applies when looking at the gross domestic product and into the lives of the jetsetters filling the coloured magazine pages, or when watching printed and electronic news media, where money is more and more the common denominator in all cases presented. I do not think most Norwegians feel «rich».

Presumptions about a society mix up myths and stereotypes with own values: What is good for me is good for you.

When studying parts of a society, such as that presented here for Latvia, these three elements are crucial for the selection and exploitation of sources of evidence and for the subsequent description of the findings. This applies both to the external observation, in this case as Latvia is experienced from the outside by a Norwegian, and for the inside viewpoint of a Latvian.

Part of this methodological issue is that myths, stereotypes and presumptions have often been deliberately made up. When the world was divided into the West and the East, myths and stereotypes about the decadent Westerners and the evil communists were parts of «cold warfare», a sort of demonisation of the enemy. This phenomenon is probably as old as human hostility itself. But in this case, decades of political wording had set up presumptions about what to expect when the iron curtain was hoisted up. Nuances in these general impressions, the official pictures, were often looked upon with suspicion, nearly as a betrayal.

Even within the Western or Eastern political blocks, or inside regions such makeshift labelling may persist: An example: Once my co-author and I were travelling together in an overcrowded St. Petersburg metro train. Then two ladies in the compartment suddenly started to talk about those unreliable people from the Baltics, a fifty year old stereotype with political overtones, a reminiscence from the Second World War, but obviously still alive.

The implementation

Establishing of contacts, setting up business, and an exchange of culture etc. has to be based on a careful evaluation of the sources of mutual information, and of the expectations held by the parties involved. Perhaps this is one of the most important lessons to learn from extracting knowledge about effects of social transitions.

Perhaps such methodological issues as mentioned here* See Hønneland and Rowe 2004. are the factors which separate the successful from the unsuccessful cooperation projects, in this case of relief projects as seen from the viewpoint of the receiver. An example of such projects were the Task Force efforts against infectious diseases, which have been perceived as successful, perhaps because the activities were set up following a plan which heavily engaged the Balts themselves, and less for domestic political profit on the side of the benefactor.

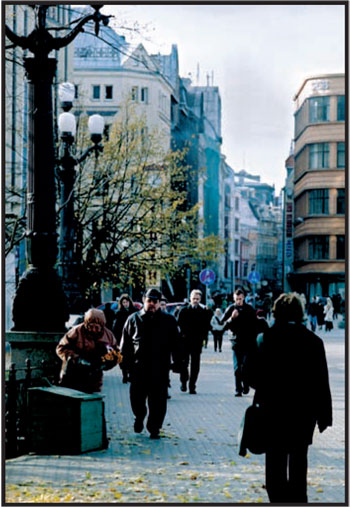

Daily life in Kalku iela, Riga 2003.

Sad sentiments on the monument of freedom (2003)

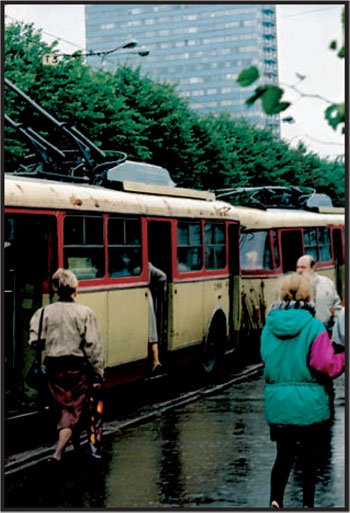

Modernization also in details. Trolleybuses in 1994 and 1999.

Modernization also in details. Trolleybuses in 1994 and 1999.

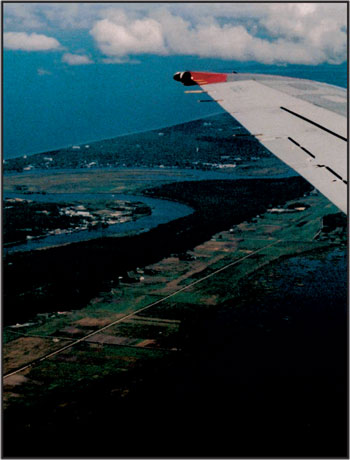

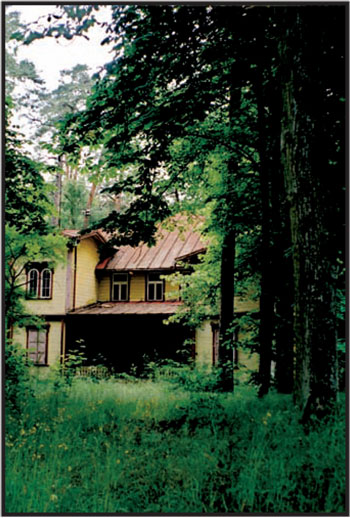

Under shifting political and social circumstances, Jurmala at the Riga Bay has held its position as a healthy resort: Playground for aristocracy in the old Russian empire, bourgeois holiday village in inter-war years, vacation area for deserved Soviet citizens, now again promoted for visitors. Here the meandering river Lielupe, separating the pine-covered Jurmala holiday area with its sandy beaches from the interior countryside (Photo 1998).

Old and abandoned summer houses with obvious potential (2002).

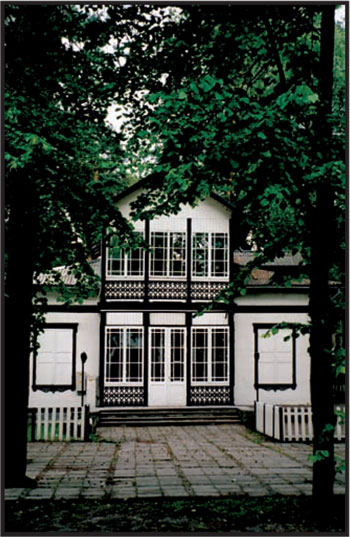

Renovated houses 2002: An attractive place for relaxation.

Jurmala 2002: A trendy destination for wealthy people, many of them from Russia.

A delivery van in Jurmala (1993) leaves every Latvian with nostalgia: This sort of trucks was distributing food all over the country in Soviet times.

Professor

Institute of general practice and community medicine

Group of medical history

University of Oslo, Norway

oivind.larsen@medisin.uio.no