Social changes and health – what is it about?

A snapshot of the background: A countryside visit

I learnt a lot about social change that summer day in 1993 south of Riga. A small placard on a billboard advertised a museum of agriculture. It was obviously located in a district down by the Lithuanian border, where Soviet style collective farming had been at is best, so the site seemed interesting and we headed for this former «kolkhoz».

The rolling landscape was pleasant. A river was meandering between meadows, pastures and vast fields of growing grain. Herds of cattle were grazing, the cows silently looking relaxed at us.

However, in between, fields lay fallow. Piles of straw from last year had turned black. Weed had taken over. There were almost no people to see, apart from in some corners of the abandoned farmland. There, some couples were working with their potatoes, cabbage and carrots, as a rule a woman and a man sometimes only with some gardening tools in their hands.

To reach the kolkhoz, we had to pass through its village, sleepy now in the middle of the day. It was looking traditional with somewhat decayed housing blocks in yellow brick and a cinema-like house with space for cultural events, a typical village in communist countries. Down at the main buildings of the agricultural plant with its huge farmhouses we met the Director, a friendly man who was pleased to display to us, the only visitors, his pride, the farming museum which he had built up during his years in charge. Soon some other people joined too, some relatives of him. They appeared to be medical professionals from Riga, coming here on their day off to have a swim in the river. Now we had additional contact points, we sat down and had a pleasant and interesting conversation on what we had seen at the museum and on Latvia in general.

The Director had a high level of agricultural education from Russia, and had been running this large state owned farm industry for years. In their spare time, he and his employees had set up a museum which revived Latvian agriculture of former times. The old single farm and village structure could be experienced by visiting his collection of rebuilt wooden farm buildings. Inside were exhibits of items and photographs from a time which had been lost, a rural society of a quite different setup, the first years of independence.

After the Second World War rural Latvia was forced through the same reorganisation as elsewhere in the Soviet Union: Private farms and estates were nationalised and combined to large, potentially efficient farm industry plants. Villages were turned into dwelling areas similar to that we had seen. For Latvia, however, an additional stress had been experienced – the hatred by the communist rulers against all remains and memories from the Latvian independence period between the two World Wars.

In the agricultural museum near Bauska 1993: An inter-war radio – a precious memory from the olden days.

The makeshift executions and mass deportations to Siberia following Soviet overtake were the ugliest part of the events which had given the preceding independence years a special flair of «good old times». In June 1940, the Soviets occupied Latvia, and only a short time before the Germans expelled the Soviet intruders, some 35 000 Latvians had been deported to Siberia. The arrival of the Germans under these circumstances of course could be perceived as a sort of liberation and left behind a general external impression of Latvian Nazi sympathy which never has totally ceased to exist.

When the Germans in Latvia had been defeated by the Soviets in 1944 and the Soviets had taken over again, hardship started anew with unprecedented force. In the years 1945 to 1949 ca. 150 000 Latvians were executed or deported to Siberia* See Baister and Patrick 2002.. In addition, there was a human drain because some people succeeded in fleeing and emigrate to Western countries. So, much had been disrupted during the war and the years that followed. It is no surprise that the independence years became something to dream about. Therefore, in Soviet times such tendencies had to be counteracted. Keeping of memories from the independence period was vigorously repressed. However, this process could only kick back and promote nationalism and a quest for new independence by the ethnic Latvians.

Of course, this fact added to the pride of the Director. He was right that his semiprivate museum was something special. He could, for example, present a radio set from the thirties, hidden away and saved from confiscation and destruction. There was also a farm tractor from the same time, a sturdy pre-war Nuffield. It was brand new and had never been used, because at the end of the 1930s it had to be hidden for the Russians, then for the Germans and then for the Russians again. Yet sixty years later it could be safely displayed. Stories like this one help to understand the background of a society facing change once more. Scepticism and irrationality are understandable.

From the collection of old agricultural equipment, tractors and machinery, we went over to look at the new garages and production lines. Huge ploughs and giant harvesters told about activities far beyond that a single farmer in any country could master.

But what would happen now? In the wake of the 1991 liberation the kolkhoz as such had been dissolved. A part of it continued on the previous line organized as a cooperative farming industry. However, some of the employees had broken out, taken over farmland and started on their own. The Director was pessimistic on behalf of future Latvian agriculture. Transfer from large scale to small scale farming would, in the first place, be severely hampered by the lack of proper competence in the agricultural population. To have been a specialized tractor driver on a kolkhoz did not imply general farming knowledge and experience. Secondly, appropriate equipment for small scale farming was lacking, and so was the infrastructure, all the way down from financing of investments to marketing of products. And for agriculture as a whole: The large former market east of the Russian border was closed for political reasons, and the new competition with import products from the West was difficult on grounds of quality.

Housing in the village of Kekava 2002.

Our conversation also touched on the new labour market: Some people believe that freedom also includes freedom from work, the Director sighed; a notion which obviously had to change as a new phenomenon appeared: Unemployment. New market mechanisms had increased prices, including on manpower. The Soviet time economy was based on a constant availability of an abundance of manpower, as everybody was entitled to a job. Agriculture was no exception. From now on, however, it became difficult to pay someone to, say, move around the many cows we had observed, in the way it had been done before.

Even on behalf of his small but impressive museum, he was worried: It would probably be difficult to persuade people to work for free in the future, he said, a necessity to maintain culture.

Some years later he had moved parts of the collections to a site at the interstate road to Lithuania and ran a tractor museum there on a commercial basis. I visited him there. The last time I drove by, the signs had been taken down and the building was empty. I do not know what has happened later to this very personal initiative of preserving virtues and culture.

The optimistic economist

Among the literature on Baltic transformation of society, three sources seem to be especially informative to Nordic readers. One of them is the 2002 book on the development in Russia, Poland, and the Baltic states written by the Danish economist Martin Paldam* Paldam 2002. In relation to life conditions and prerequisites for health, his analyses of the old Soviet society, the new liberal market society which is ahead, and the transition process in between are very interesting.

On the mental side, the strong traits of unprotected repression, surveillance and decision-taking from above had to be replaced by a situation where individuality and personal responsibility carry heavy weight. In addition to other perspectives, these markers should be seen from a psychological and sociological point of view. Following Maslow’s classic hierarchy of needs* Maslow 1954, the bottom layer in his metaphoric pyramid includes basic life saving demands for food, protecting housing etc. The next step includes safety, and then one proceeds upwards to the needs which ask for fulfilment when the others below already have been covered. Thus, the top of the pyramid is something as esoteric as the need for realization of self. If basic levels are covered by central authorities to a degree which by and large is excluded from public discussion, and kept there, a basis for satisfaction should be present.

However, to cope with everyday life, widespread personal contacts and partaking in networks were necessary in Soviet Latvia. In the liberal market society and modern democracy, such networking easily gets another colour: the negative taste of corruption. In the old Soviet society, informal networks which exchanged service for service were a necessity – both on the personal and corporate level. Paldam points out and explains paradoxes. One of these is a state run company, under the fixed prices system, paradoxically could have to keep the production expenses on a maximum as a strategy for obtaining success and achievement of planning goals. This could result in demands for excess raw materials and additional manpower which could be put into a widespread parallel, clandestine, informal and in principle prohibited barter economy. In a liberal market society with modern democracy it usually is the other way around: Profit and success depend on maximizing prices and minimizing costs. Use of personal contacts and informal networks to achieve commercial goals and own prosperity was formerly deemed acceptable. To transfer minds from perceiving something to be a virtue and an asset to become the opposite, is a difficult venture.

The control mechanisms required from authorities above included linkage of personal professional training and careers to the political party system and its «nomenklatura» for possibilities and positions. In addition, the system included an elaborate structure for reporting of personal behaviour.

It adds to the picture that the strategy of migration, moving to another place to pursue individual preferences was almost absent because of strict regulation. The word «atomization» has been used for the internal mental dissolvement of a seemingly tight and structured society, which appears when surveillance is everywhere and the individual has to develop suspicion as a strategy for survival and needs to have silence about one’s own information, preferences and opinions as a virtue.

This behaviour is an obvious mental strain in itself for the individual, but when it is more or less a key characteristic of many people now adjusting to the new situation after change, it becomes especially important. If put into the Maslow metaphor, to reach the top level of self-realization, is logically impossible without mental change, simply whilst realization of self implies free decisions and expressions of feelings and thoughts by the individuals.

The extension of the concept of health, as seen in Western societies since the end of the Second World War and the launch of the new and wide definition by the World Health Organization, presupposes the uphill climb on the Maslowian pyramid. Health is not a mere case of biological function, it also implies social, mental, and political goals to be fulfilled. Social issues have been medicalized, as have also preconditions for mental health. A logical connection has been made between the principles of human rights and the concept of health.

The logic of the Soviet type society implies that personal health and conditions for health by far is a matter to be handled by society, and by and large outside the own responsibility of the individual. Society takes care of you, even if it is not done in the best of ways.

When discussing the part of the transition process which relates to health, it is important to remember that health as a value might have a different position in people’s minds, after the change, than could be expected. Also in the field of health, the society in transition poses far more individual choices to be made than before, more options to be considered. When a health promoting life style and the perusal of «fee for service» health personnel simply cost money, what is the outcome worth? Why should I care about preventing myself from contracting contagious diseases, when antibiotics are at hand? Such sentiments are easy to understand, especially among the young and healthiest cohorts of the population. But, responsibility for one’s own health is not fully discovered until the hardships of reality appear. When «demandelastic» values have to yield to your nearly «non-elastic» medical needs, and there is nobody to cover them without substantial remuneration, not from the state but from yourself, a problem has been discovered too late.

An economist like Paldam does not cover health and health conditions. But from his considerations and discussion on the changes, it is obvious that there are quite large attitude changes which have to follow suit, not only changes on the economic and the social surface. He tries to find examples in history which can indicate a time perspective when Latvia’s change will be complete, but he finds only little of predictive value and ends up in an optimistic mood: Modernization will probably occur at a fast pace.

Riga Hospital Number One, photographed in 2004.

Down to the hard facts, but how hard are they?

Health and social conditions come to light through statistics. Opinions, impressions and perceptions are one side of the truth, but statistics reveal the other, the naked reality. That is how we think – at least are supposed to think – in modern Western societies.

However, what is truth? If you attend a conference on health and social conditions and papers are given on changes during a period when central paradigms have changed, such as they have in Eastern Europe in the late decades of the 20th century, you often will have been astonished on two levels.

The first one relates to a paradox which also has been covered by Paldam in his book, that is, that figures from the old society often describe a situation which seems much better than you could observe by yourself. On the other hand, statistics from the changing or changed society frequently indicate a misery which contrasts appallingly to the flourishing you see with your own eyes in the streets. This paradox is part of the dilemma mentioned above: Is reality a subjective, perceived reality or is reality the objective, registered reality? Let us leave further reflections on this topic to the philosophers, yet to conclude that the basis and objectives for statistics may be different, and may cause peculiarities when dealing with time series covering a period when principles shift.

Then to my other level of astonishment: Very often people reading their papers on conferences neither seem to realize this above mentioned phenomenon nor comment on it, and that astonishes me strongly. There are at least two faces of truth, but they are difficult to combine for comparison. Without such consideration any comparisons across paradigm shifts are worthless.

In his introductory chapter «Studying social problems on the basis of official statistics» in a book on alcohol and drugs, Leifman* In Leifman & Henrichson 2000. discusses these methodological issues in more detail. He emphasises that official statistics are a product of perceptions all the way from what data have been collected, over how they have been worked up, to what selection of data are presented, and in which way.

And he stresses that when data on a society have been published, they in turn start shaping the society. Statistics presented on the basis of a political ideology need not be false. Figures may be individually correct, but the overall picture they render, depicts a political reality. Leifman even refers to studies on the use of language in the former Soviet republics. Language showed logical similarities to statistics. There were conflicting encounters between reality as described through language and the society as it really was. To paraphrase: The spoken words were the ideal, while the objective reality was a deviance. The introduction of glasnost in the 1980s made society transparent and linked descriptions and reality more tightly to one another, one of the most important social achievements, it is argued.

Said an Estonian official representative, from the national health authorities, on a meeting I attended in 2001 on the combat of contagious diseases in the Baltic region: Infectious diseases did not constitute any problem in her country. Her audience, consisting of infectious disease specialists, held other information, to express it carefully. But she obviously represented the former society: What she said was not wrong, when she insisted that infectious diseases were no problem. She did not pretend that the diseases didn’t exist, merely that they were no problem. That was her perception, and probably that of the official administrative body she represented, as she was the envoy. Needless to say that one of the objectives of the conference was to shed light on and to change the perception of infectious diseases, one of the keys to being able to combat them.

Latvia and its Nordic neighbours

In 2000 the Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia published a collection of statistical data covering the Baltic and the Nordic countries* CSB Latvia 2000., about the period 1995–1999 and in addition containing some figures from 2000. Even if these years do not belong to the time before the changes started, and in no way represent the end of the transformation, they give a baseline for looking at the situation, and the data should presumably be reliable and lack methodological and ideological biases.

Latvia covers 64.6 thousand square kilometres, approximately one fifth of the areas of Finland or Norway. But as Latvia has 38,5 percent agricultural land and 44,2 per cent woodland (2000), as compared to Norway with its percentages of 3,2 and 21,7 (1989) respectively, remarkable differences are set by nature. Economic comparisons are difficult to perform – and especially in a period of transition. However, the three Baltic countries lie substantially behind the Nordic countries. By 1999, Latvia as the lowest had a gross domestic product per capita of 5800 Euros, as compared to Norway on the top with 26562 Euros – for further comparisons see our tables!

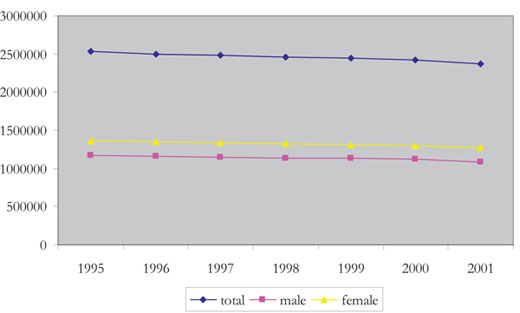

By end of the 1990s, all the Baltic countries had experienced a slight population decline; Latvia ending at 2 424 000 by 2000. The Nordic countries showed a small increase, with Norway up to 4 478 000 by 2000.

The 2001–2004 «Task Force» project set up after an initiative on prime minister level in the states around the Baltic Sea, was unique in at least two ways: It served successfully its primary intention, i.e. to promote local work against contagious diseases, and secondly to establish lasting medical contacts between the Baltic States and the other participating countries* See Siem 2004, Hønneland/Rowe 2004, and Siem 2005.. The picture is from a start-up meeting in Oslo on Sept 7, 2000. (The fire alarm went off in the meeting building so everyone had to evacuate, a golden opportunity for taking a group photograph outside the entrance!)

The sex distribution is interesting: Whilst Denmark, Norway and Sweden counted 102 females for every 100 males, Iceland counted 100 and Finland 105 (1999), the Baltic States were on another arena: Lithuania has 112, Estonia 115 and Latvia 116 females per 100 males. This of course points at an excess male mortality rate which is also confirmed by the statistics. However, data on health and health care are not detailed and the statistics contain notes that say that parts of them are difficult to compare with other countries. That for example traffic accidents and male deaths related to alcohol are of special importance in the Eastern transition countries, is tacit knowledge. Medical experiences from medical personnel may perhaps give better or at least supplementary impressions than statistics here? Anyhow, Vasaraudze* In Aasland 1994. presents some figures: In the period 1992–1994 the mortality among the working age population showed a substantial rise from 5.22 per thousand to 7.81. Among males in working age the increase was even more appalling: from 8,23 in 1991 to 12,49 in 1994. In Latvia in general diseases of the circulatory system, malignant neoplasms, accidents, injuries and poisoning top the list of causes of death. An example: In 1994 56 per cent of the deaths were caused by circulatory disease, while the level in Western Europe is 35–40 per cent.

The areas which call for attention thus are twofold: One is the situation for health, the other the causality behind the changes in health going on in the inter-union period.

However, when looking for changes in health issues and in conditions which influence health over a period in order to do comparisons, it is important to keep in mind that changes are going on also in other fields. Some of these changes may draw little public attention because they are continuous; they are only slow processes taking place over time, so that their impact evades attention. There may also be a less documented causal relationship to the process of our core interest, which here is the change in the Baltic societies.

Examples: The Nordic countries have hailed the notion of the welfare state as a hallmark after the Second World War. However, since the 1970s the welfare state principles have steadily been endangered, and in fact a gradual dismantling has taken place. The reasons for this development are multifactorial and have probably mainly to be sought amongst steady changes in attitudes in the population and among their politicians. The real outcome of politics, as a rule, appears in the budget with its blank face, and cut-down health budgets are the result of political decisions, the result of choices between priorities.

Diagnosis |

1999 |

2000 |

2001 |

2002 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Diseases of circulatory system |

746 |

753 |

783 |

778 |

Tumours |

237 |

237 |

248 |

246 |

Injuries, intoxications, consequences of external causes |

162 |

159 |

157 |

157 |

Diseases of digestive system |

39 |

42 |

45 |

43 |

Diseases of respiratory system |

34 |

36 |

33 |

36 |

Diseases of nervous system |

10 |

11 |

15 |

17 |

Infectious and parasitary diseases |

17 |

16 |

17 |

13 |

Causes of mortality |

2002 ( %) |

|---|---|

Diseases of circulatory system |

56,0 |

Tumours |

17,4 |

Injuries, intoxications and consequences of external causes |

11,3 |

Diseases of digestive system |

3,2 |

Diseases of respiratory system |

2,4 |

Number of permanent residents

Leifman* Op. cit. points to how the Finnish economy suffered remarkably when the Soviet Union, a major trade partner, dissolved and exports diminished substantially. The income loss accelerated the pressure on the welfare state in that country. However, the explanation might not be that simple. Is it possible that the concept of the welfare state, when having attained a certain level of development, simply nurture factors which erodes its basis? Harjulas study of Finland in the 1960’s might indicate the presence of such mechanisms* Harjula 2004., as do experiences from the post-industrial Western welfare societies turning towards a market economy thinking. Less space seems to be left for the long term planning and the social tailoring which were chosen as appropriate tools for public health work in the political settings where welfare ideologies were born.* See e.g. Evang 1961.

Of course, the opening of the borders also opened up mutual opportunities, silently changing conditions for the better on both sides of the previous iron curtain. On the Baltic side, imports and trade contributed to an increased living standard, an undisputed prerequisite for health.

On the other hand, from the West there often is only a faint distinction between foreign investment and foreign exploitation. It should not be concealed that westerners who were less suited as ambassadors for their countries also saw possibilities for carrying through activities lying on or beyond the brinks of law and morality. Seemingly brave relief schemes may be two-faced, when projects mainly fit for domestic purposes on the side of the donor appear as a mere annoyance to the receiver.

Yet on the Nordic side there still are some quite less visible examples of influence: Cheap, imported labour from the Baltic countries, done by people who want to earn money they definitely deserve, causes internal concern. There is a moral side attached to the wage differences, but also a fear of competition. Similarly: Cheap forestry products from the Baltic States may disturb the domestic market in the Nordic countries on grounds of prices, another silent change.

For the sake of completeness it should be mentioned that there are skewed sides of the Baltics too: Baltic cities have taken over an important role as shipping ports for drugs, tobacco products and other items meant for the Nordic illegal market, together with prostitutes and people with a criminal record.

Context is usually complicated.

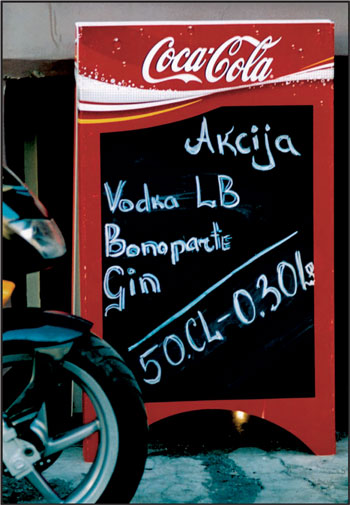

Riga, May 2004: What about prices and alcohol politics? Here, vodka is offered at beer price.

Tourism under development: Restaurant near Sigulda waiting for guests (2004).

Riga Valnu iela 1993.