Conclusions: What did we learn about social change and health?

The case of Latvia

Through our own medical and teaching work, our own observations of the Latvian society, the information collected by our student groups, our own research projects and by participating in the Task Force on Communicable Disease Control in the Baltic Sea Region we learnt a lot. Some of it has been presented on the previous pages – facts and figures which do not need to be repeated.

However, the overall experience has been that the Latvian society has passed from a situation which, in principle, was well organized – in spite of its faultiness in serving the individual citizens in a proper way. Then the society passed through a period with widespread chaos in financial and public services, leaving large groups of the population with unpredictability, insecurity and problematic living conditions. Gradually a reshaped setup emerged, based on market economy and European Union structures.

During this process a continuing and general increase in living standards has taken place, somewhat relieving the burden on the most vulnerable parts of the population – particularly the elderly. But there were also other groups with living conditions at stake – the low-income groups, especially those in public service where opportunities to supplement one’s income were few.

Was there a health crisis due to poverty? Poverty is difficult to define in changing situations like in Latvia. The new consumer society places new demands, so that if poverty relates to the gap between perceived needs and means to cover them, these requirements and wants should be studied in light of what has to be regarded as the acceptable minimum, the previous situation, and Western standards. Thus, the poverty problem is complicated to assess, when it comes to the impact exerted by living conditions on health. But the widespread search for extra jobs speaks for itself and is felt to be a necessity by many people.

During the first part of the transition period, morbidity and mortality figures rose, in particular for infectious diseases, reflecting failure in preventive measures and in disease control for those affected. Changes in lifestyle may also be an explanation, but a weighting of this factor as compared to the impact of the insufficiencies of the health care system, remains to be done. What were the changes in lifestyle for the majority? Probably not that much. As soon as a basic family income had been established, adjusted to the new price levels, the general impression is that life went on as before, apart from the important fact that food and necessities were now constantly available – if then money to buy was at hand. The necessity of the Soviet era informal networking system in order to get what you wanted, diminished.

Whilst health gradually moved from being a societal issue to one of personal responsibility, it became a sort of commodity in your thinking: You could invest efforts in preventing or treating an ailment, or you could leave it and choose to use your resources on other commodities of greater preference. An example: In the case of infectious diseases, we found a perception of risk that placed more trust on antimicrobial treatment than on preventive measures and behaviour. Such a fact, of course, has implications for the setup of disease control. Change from free health services to a fee-for-service system indeed settled the shift of responsibility from the society to the individual, as health and sickness now had a price in Lats and centimes. That health was transformed into a commodity, was a new and confusing experience.

The establishment of a new primary health care system with patient lists assigned to general practitioners, broke the tradition of the Soviet specialist and hospital oriented health care, to now comply with new demands for medical and economic efficiency. However, the Western widened concept of health also has seemed to develop in Latvia. What this will mean in terms of future expectations of primary health care is unclear. But a special topic pops up – the burden of stress in those age groups who had to adjust to uncertainty and hardship during the transitional process should not be underestimated. Perhaps we will see for a while typical «postmodern» patients in Latvian waiting rooms, suffering from new and unaccustomed forms of stress?

The route that the development of Latvian society should take after the exit of the Soviet Union, was not clear when it began. The Latvians chose, early on, to aim at the EU membership which was achieved in 2004. This meant that a structure for the future society had been established which also contained standards for living, conditions for health and for health care. Future evaluation of the development of health therefore should be performed in an EUcontext.

Under the skin

Our methods for seeking and evaluation of knowledge call for reflection, at least by ourselves. An example: Look at the pictures from Latvia. Taken together they should give an impression of how the country and the society appear, but we have argued that there are interpretation problems. The view from the outside and the view from the inside are different. To get under the skin of a society requires both aspects – the presumptions, knowledge and values from outside that encounter presumptions, knowledge and values from the inside. Here we think that our cooperation has been fruitful. Our numerous discussions have convinced us that attempts to get under the skin of a society is indispensable both in studies of social change, and when implications of the knowledge and skills emerging from the studies are to be used in «real life».

Whilst 23 years, almost a generation, separate the ages of the two authors, this has not been felt at all during the project cooperation, but it might have influenced the interpretation of our findings, emphasising some timeless experiences:

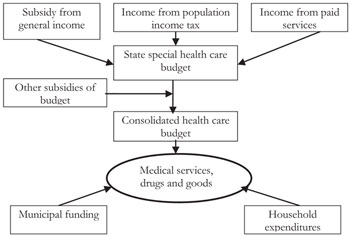

Financing of the health care system in Latvia, as it was in 2001

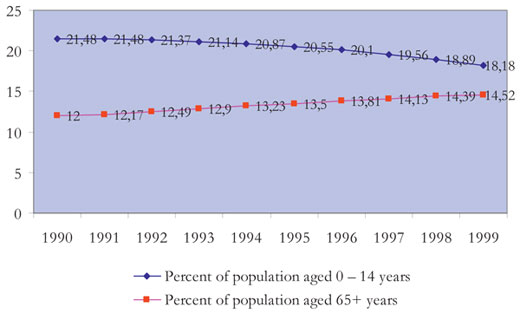

Ageing of population

General principles?

To an elderly Norwegian observer there has been a striking trait whilst getting to know the Latvian transitional period, a sort of «déjà-vu»: In one decade a similar process has taken place which in Norway took forty years. Latvia’s years between the two unions, in a way, is a repetition of the Norwegian development, but much faster.

Post World War II Norway was not unlike Latvia after independence. Shops with little to offer, people who needed informal networks to make ends meet, political tensions, economic reorganisation, strong central leadership and other factors found in Latvia, were also found in Norway, although in other and context-dependent forms.

In Norway, there was a gradual adoption of a dominant market economy, and a slow release of market forces via a highly political process with pros and cons. In Latvia this happened in an explosive manner. To observe Latvia in the transitional period as described here, in a way, was to go back in history, where experiences could be directly compared step by step.

But when does the comparison end? Should Latvia in 2005 to be compared to Norway in 2005, or to Norway at some point in future? If so, Latvian society is of special interest.

Does the Latvian experience point to the presence of some general principles appearing when societies change? If this is the case then studies of social history should be upgraded to tools for societies in transition. Monitoring projects of societies undergoing change should be mandatory, in these cases.

A visitor’s epilogue

When coming to Riga in 2005, it is almost like visiting any of the EU capitals. In Latvia, the recent past has become history. Milda is again overlooking the city. Let us hope that she takes care of her virtues.

A Latvian prestige product of the 1930s, the stainless steel «Minox» subminiature camera, one of the most popular export articles of the time.

The cars in the Latvian streets have changed dramatically. Here are two brands, previously seen frequently: To the left a Russian «UAZ», used as an ambulance, photographed in 1998; a sturdy 4x4 vehicle, still in production. The minibus to the right is a Latvian «Latvija», used all over the eastern world, but not in production anymore. This one has Latvian licence plates, but is photographed on an excursion to Tartu in Estonia in 1994. Of course cars like these brought you from A to B, but when more sophisticated Western and Japanese cars became available, they met heavy competition.

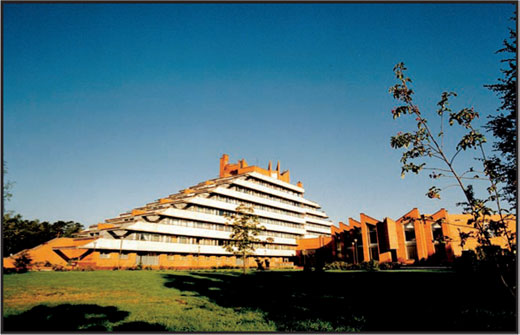

From Soviet era health care: The picture shows a hall in the rehabilitation centre in Kemeri, near Jurmala

From Vaivari in Jurmala, which was a recreation centre for Soviet cosmonauts. Both photographs are from 1994.

and