Changing the basics

Aadne Aasland, Director of the so called NORBALT project, did not conceal a certain pride when he wrote the introductory chapter to the book he had edited on social transformation in Latvia* Aasland 1996.. On August 31, 1994 he reports, Latvian newspapers informed that the last Russian soldier left Latvia. The same newspapers also told about the large living conditions survey which was to be launched shortly afterwards as a joint venture between the Central Statistical Bureau of Latvia and the Norwegian Institute for Applied Social Science called Fafo. In September 1994 a sample of more than three thousand Latvian households were approached for a study of their living conditions.

Fafo had experiences with previous living conditions projects, e.g. a study in Lithuania 1990–1991. This project was larger, comprising of the three Baltic states, in addition to St. Petersburg and Kaliningrad in Russia. In five areas, 16 000 households were studied. Needless to say that these data on living conditions constituted a baseline for practical, local political decisions, and for social science studies of wide interest as well. The Baltic region after the dissolution of the Soviet Union has been and still is an unprecedented laboratory for social science work.

Aasland reviews the background for the transition. Amongst other issues he takes up how the whole liberation process started with discussions about how Latvian economy, heavily dependent on centralised Moscow-led politics, could face a stagnation in Soviet economy as a whole. Over the years, the Latvian conclusion in this matter became far wider – independence.

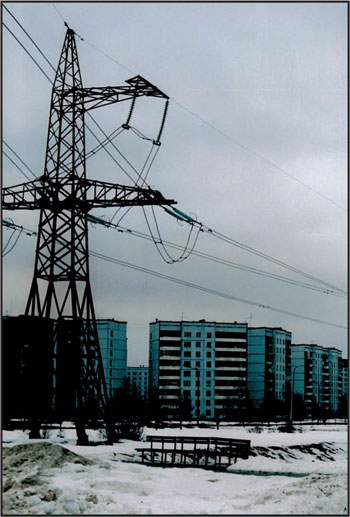

But the Latvian economy in its turn was heavily dependent on a workforce recruited from the East. To be moved from Russia to Latvia was often no bad fate: To get proper housing was a general problem in the whole Soviet Union and in Latvia houses were built for the newcomers, whilst the Latvians had to wait for years. Still in 2005, housing projects with unfinished buildings can be seen. The migration of Russians came to a halt before the houses were finished.

The Russian part of the population was at its largest in the cities and in other industrialised areas. To calculate the number of people may give different results, depending on the means of counting. If we say that around half of the population consisted of ethnic Russians in the 1990s, less than one half of them were Latvian citizens. After independence, Latvia launched schemes for citizen applications where proficiency in Latvian language was among the requirements. As much of the schooling system had used Russian as a working language for decades, this obstacle was a serious one, especially for persons coming from regions of Latvia where Russian had been predominated

To a visitor from abroad, the Latvians’ claim of national independence and sovereignty in all matters during the transition period, appears as a game with large values at stake. Of course it is in the national interest to keep a major part of the population as loyal Latvians, so the language issue obviously had and still has political overtones. On the other hand, to a visitor it seems to be risks present which require a delicate balance: Apart from the mighty sleeping bear across the Eastern border, who might be woken up by noise from Latvia, there are risks to develop ethnically based class differences and settling geographical, social and cultural differences in a way which may cause future problems. A visitor may wonder to what extent the relatively higher living standard in Latvia, than in Russia, has worked as the major peace-keeping factor between the two parts of the population. Probably, the ethnicity issue will gradually disappear.

Aasland touches on the difficulties in defining what living standards really are, and in particular what a high standard is. Shortly, he resumes in his discussion, living standard on the one hand implies resources, where health is one of the ingredients. On the other hand it is also required to have arenas of action where these resources can be converted into other assets. We might take his discussion even further in light of some additional points.

One of them is that satisfaction depends on previous experiences. A survey on housing satisfaction, performed in Norway in the 1940s among people who had moved into a newly built housing area, was confounded by the fact that the previous housing conditions has been so bad that everything seemed much better. A study of the function of a new housing project became instead a study of the past.* Discussed in Larsen 2000.

The sense of normality, i.e. the standard for acceptance, is another point which is subject to change in time and place, and among other factors is influenced by information. A Latvian tourist guide, a retired teacher of my age, around her late sixties, recalled her childhood in the Riga outskirts. What she described was a happy period of her life, although an objective assessment of the details of the story revealed rather austere conditions. But so had been her concepts of normality, this was what she knew of, and the situation was perceived as safe and comforting, containing other elements of what we today include in the term «living standards». However, what struck me, was that that which she described was very much like my own experiences growing up in Norway during and after the Second World War. This confirmed to me that comparisons of living standards should be adjusted for historical context.

The romance of the old villages – a pastoral scene painted by Augusts Anuss (1893–1984) (National Gallery, Riga, special exhibition 1993).

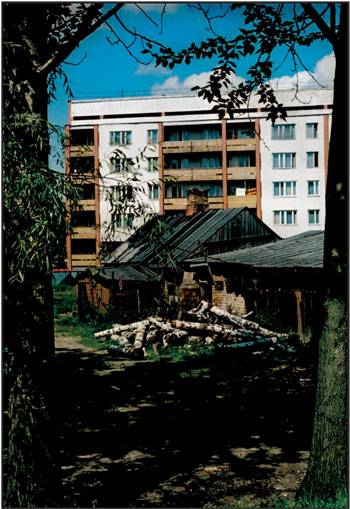

Romance of the old villages – the real world (Tukums 1993).

When studying health, the issue of normality is important, because the level of acceptance is one of the factors which seem to explain how high health ranks as a priority. There are historical clues that, for example, changes in attitudes towards infectious diseases have had significant influence on their management.* Larsen, atlas 2000. Back in the far 18th century, high mortality and a ravaging morbidity obviously were accepted as part of life. When looking to the health conditions in modern Latvia, a sensible baseline is the morbidity and mortality in Soviet times.

The 1994 survey contained data on health perception. Vasaraudze concludes that when comparing 1992 and 1994 data from Riga, there is a substantial increase in negative over all assessments of health. This is interesting, also because the increase should indicate a potential for introducing preventive efforts. However, to voice dissatisfaction is not the same as putting health promoting measures on the top of the personal priority list.

A third point deals with preferences, visions of the future. Let us take again the example of housing, where your perception of the housing quality very much seems to depend on your own relationship to your home. The same house or apartment may be perceived as good or bad on grounds of phase of life and space needed. On the other hand, you will perceive the standard different if you are about to move, that is to fulfil your preferences in another house. However, if you are not able to move for different reasons, you will perhaps dislike your dwelling more than it deserves* Larsen 2000.. This factor makes comparisons between e.g. traditional Soviet style Latvian housing and housing in free market countries difficult.

There also are connotations to housing which belong to the aesthetic and cultural domain and are irrelevant to the core of conditions for health. In most of the communist world traditional villages were replaced by apartment blocks. These blocks provided flats of a certain standard, but they also represented a social engineering process put forth by the authorities and thus emitted political signals. Their acceptance by the population has to be seen in light of that. A dislike of the housing may be a converted nostalgia* In Sweden a similar process also has been going on, see Larsen 2000.. In the National Gallery in Riga there is a painting by Augusts Anuss of a village scene, reproduced here, contrasting new blocks with village huts in an almost pastoral setup. A corresponding photograph makes clear that a difference in standards also should be taken into account when considering the former housing policy. However, another part of the story is that many of these blocks have been built with low quality materials and improper workmanship, so that major and complicated restoration will be required.

Housing complex in the eastern outskirts of Riga (1997).

Aasland and Tyldum* Aasland & Tyldum 2000. compare the basic living conditions between the three Baltic countries as they were in the period 1994 through 1999, revisiting the 1994 data and drawing on a 1999 follow up study. For all three countries the figures tell about general modesty. In a health perspective modesty does not necessarily imply a health hazard, in many cases on the contrary. But modesty conflicting with personal possibilities and preferences may be a mental strain which includes health impairment.

However, some of the living standard markers may give interesting information. For instance the unemployment rate decreased from 17 to 12 per cent in Latvia in the 1994–1999 period, in contrast to Estonia which had a stable 10 per cent rate and Lithuania, where a 10 to 17 percent increase took place. The authors also remark that the impact of unemployment on household finances is less marked in Latvia. A feeling of job insecurity was very common in Latvia in 1994, as expressed by around seven out of ten informants and more than in the two neighbouring countries. However, this sense of insecurity was diminished by 1999.

In Latvia around four out of ten pre-school children attended a kindergarten, which is an increase from 1994, a tendency also found in Estonia and Lithuania. However, in Latvia the kindergarten expenses were the highest.

Health mediating factors, such as the setup of the health services are different in the three Baltic countries, and for Latvia conditions have also been changed substantially through the years since the Soviet period. It remains to see how morbidity and mortality will stabilize in Latvia when the country has settled as an EU-member state. It also remains to be explored and discussed which factors have had the strongest influence on the health situation during the transition period; the physical, social and economic environment, or the shifts in general attitudes following the changes in the basics.

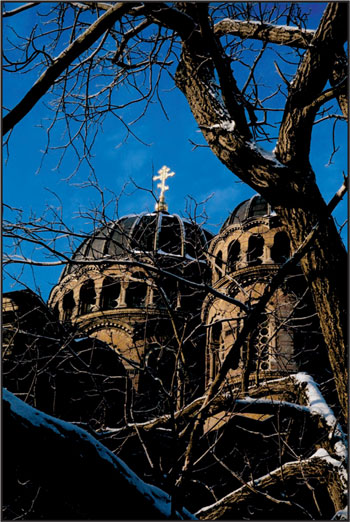

Riga orthodox cathedral (2002).

Old Riga street (2002).

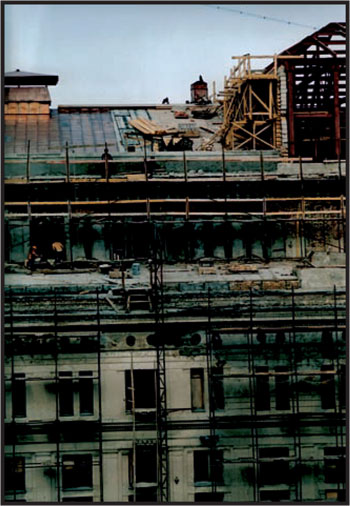

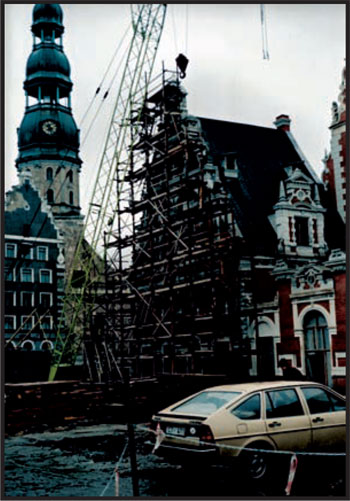

Riga opera reconstruction 1993: Rebuilding national identity.

The National Opera shining in the darkness 2003.

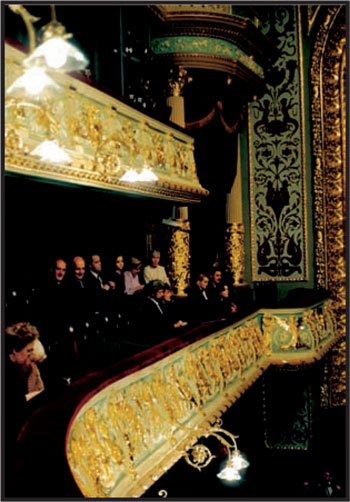

Riga opera audience 1996.

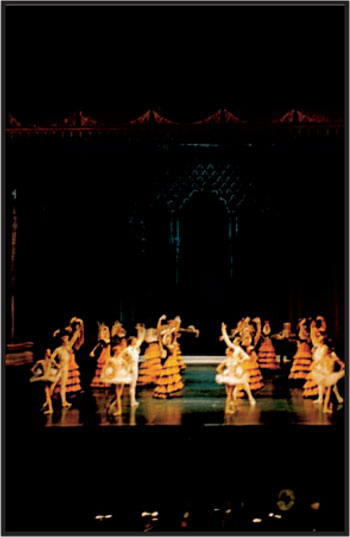

Riga opera ballet (2001) – pride is back!

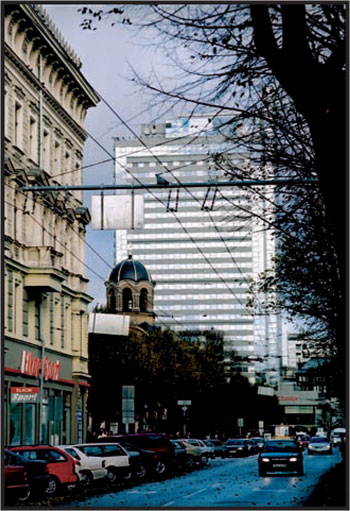

Riga Hotel Latvija 2003: From Intourist crowds to Western businessmen – and new tourist groups.

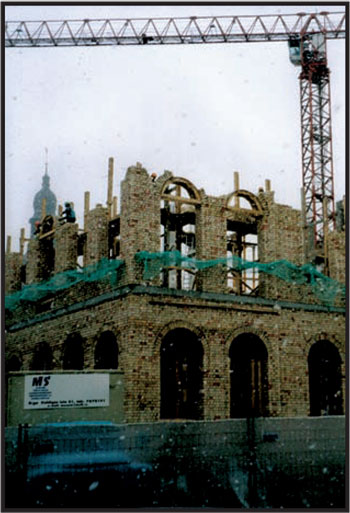

Riga town hall under rebuilding 2001.

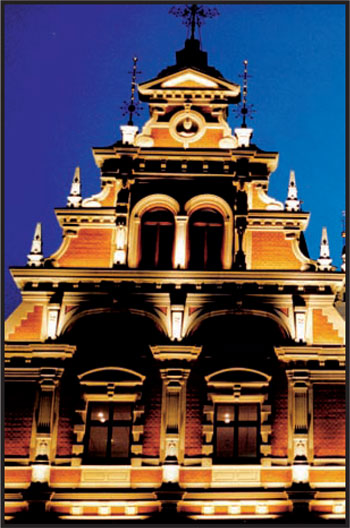

Riga prestige rebuilding 1998.

Rebuilding completed.

Professor

Institute of general practice and community medicine

Group of medical history

University of Oslo, Norway

oivind.larsen@medisin.uio.no