The role of Norwegian nurses in the fight against tuberculosis 1912–1940

Michael 2005; 2: 277–92.

Background

In the time between the first and the second world wars tuberculosis was an important cause of death in Norway. Although the death rate began to fall after 1925, as many as 12<[FO]>% of the deaths in Norway were caused by this disease in the period between 1925 and 1935. The fight against tuberculosis was not over before the fifties. Then the death rate was reduced to only 2<[FO]>%, mainly because of social development, increasing general welfare, vaccination and specific therapy (1).

During the 400 year anniversary of the Norwegian public health services in 2003 many people looked back at «the glorious fight» against tuberculosis in Norway. They spoke about the contribution of the Health Authorities, the doctors and of the contributions by humanitarian organisations such as Norske Kvinners Sanitetsforening and Nasjonalforeningen for folkehelsen. These two organisations were founded about 100 years ago. They made a particularly strong effort to fight tuberculosis in the first part of the twentieth century. Historical studies, however, indicate that they were in constant competition for donations and had many disagreements about which organisations were to be credited for the positive results of the work (3, 4). Few spoke about contributions by nurses in the fight against tuberculosis, but many nurses were highly devoted to this task and some of them even were employed by these organisations.

The first formal education for nurses in Norway started in 1868. During the following 60 years, there were no public regulations regarding nurses’ education. Such guidelines did not appear until 1948.

In the years around 1900 many hospitals and organisations realized the necessity of offering formal education to women in preventing illnesses and in nursing the sick. Education for nurses was therefore based on the needs of the organisations or the hospitals. It was easy to attract students. When the nurses had finished their education, they were obliged to work wherever the organisation or the hospital needed them.

The results coming out of this system were that nurses had different types of education, employers and areas of work. Usually they identified themselves with the institution where they were educated. A nurse educated by the Red Cross, as an example, entitled herself Red Cross Nurse (4, 5, 6).

When Norsk Sykepleierforbund (Norwegian Nurses Association) was founded in 1912 this organisation included all nurses regardless of their title. The organization attracted many members in a relatively short time. It had its own periodical «Sykepleien» (the Norwegian word for «nursing») which published 11 yearly issues. The first editor was the powerful founder and leader of Norsk Sykepleieforbund Bergljot Larsson (1883–1968) (7). The journal presented many articles about the organisation’s activities, but also brought papers discussing the special nursing needs for patients with different diseases. However, it is important to have in mind that this journal was not intended to be a medical or scientific journal, a fact which is important when searching for pure medical information on its pages. Nevertheless, the periodical «Sykepleien» is an interesting historical record as to the standardization of professional knowledge offered to a numerous group of nurses.

Material and methods

A systematic search for articles about tuberculosis in the magazine «Sykepleien» from 1912 through 1940 was performed. I looked for:

What the nurses did to inform their colleagues about their care experience nursing patients with tuberculosis.

What they did to prevent the disease in different fields.

What the doctors and others told the nurses to do, and what they told about nurses’ participation in this effort.

The search resulted in 24 relevant articles which in one or another way were answering these questions. First of all this indicates that tuberculosis was an important topic in the period studied. The articles concentrated mainly on nursing practice, competence and scientific research.

Nursing practice

Through their magazine, nurses were in many different ways encouraged to fight tuberculosis and its consequences. Important lectures were printed as articles. An example of this is the lecture: «Directions in the fight against tuberculosis», given by the doctor Johan Fredrik Bratt (1900 – 1957) at the General Meeting in 1931. The speaker started with dramatic words like these (in translation): «This giant among diseases destroys the society in a slow, persistent duel. This fight is taking place all over the civilized world. In our small country alone, millions of Norwegian kroner are sacrificed, and thousands of people are at all times involved in the fight». And he continued: «The well trained, scrupulous nurses are the hard core of the army in the fight against the White Plague. Remove these nurses and the fight will be hopeless» (8). The doctor was obviously inspired by his audience of several hundred nurses.

In their daily jobs the nurses faced the infected patients both in the institutions and by home care nursing.

Home care nursing

Visiting people with tuberculosis in their homes was the responsibility of nurses mainly employed at local health stations. During visits in the homes the nurse «has to try to be the friend and adviser of the sick person, and not an inspector on behalf of the society. Force is an inferior measure in the fight against tuberculosis» an article told its readers (9).

Some places the nurses created a file and filled in a report on the family members after their first visit. The file followed the patient and the family until the patient was either dead or cured. The nurses made an effort to follow up on the children and to monitor them throughout their childhood. Based on the nurses’ reports the doctors decided what kind of treatment was needed for the patient and the family. In this way the nurses’ surveys and reports were of major importance to the doctors, who in fact seemed quite dependent upon the work done during home visiting by nurses (9).

The health of children was a major concern to the nurses. (Private photo ca. 1925)

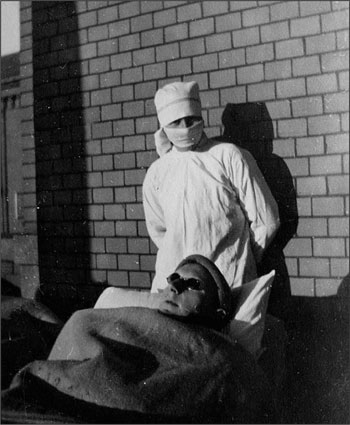

Correct sunbathing and air treatment were important. (Private photo ca. 1918)

If necessary the nurses encouraged the infected people living at home to accept hospitalisation for treatment. To succeed in these tasks the nurses needed to show tactfulness, insight in human nature and patience. (9)

While the sick family member was away, the nurse was responsible to organise the home in a way that reduced the risk of a further infection. First, the family was to be trained in hygiene procedures. Secondly, the home was to be thoroughly cleaned. If cleaning help was used, the nurse was supposed to supervise the work. Quite often, however, the work had to be done by the nurse herself. Thirdly, after hospitalisation of a patient, the nurses were responsible for investigating the social situation of the patients and their need for further economic support. This was before the days of social workers and shows the variety of responsibilities for the nurses in the inter-war years.

The number of nurses employed to take action in the homes of the patients varied between different municipalities and places. As early as 1919 in Oslo, the capital of Norway, there was seven nurses who exclusively worked with home visits to recently infected patients. In addition, 15 nurses were supervising the people that not only had been infected for a long time, but were poor as well, and who received public social support. These nurses were characteristically named «nurses for poor people» (9).

Smaller places had fewer resources for this line of work, as compared to Oslo; in the city of Narvik only one nurse was employed. She did home nursing on behalf of the health station, and she was the matron of the tuberculosis nursing home of the city. (10) Many other nurses in Norway faced a similar lonely work situation. This created a need to discuss mutual problems with others. One possibility was to use the journal for debates. The debate on the proper way of how to wash the dishes is an illustration of what they needed to talk to other about. Dish washing might seem like a minor issue for discussion today, but how to boil plates and silverware correctly was an essential task in combating infectious diseases. It was particularly important where many people were fed during parties and in public dance halls. In this perspective, the debate was highly necessary. (11)

Nursing in hospitals and nursing homes

There was a general agreement that a nurse, wherever she worked, had to be responsible for two areas: To help the patient and to prevent the spread of infection. This was particularly important when she nursed the seriously ill patients with tuberculosis. The work was demanding and challenging. A letter to the editor in 1914, however, shows a note of optimism (in translation): «Dear Editor, We have worked with the infected patients for three months, and it is an encouraging work. In this short time we have 14 patients showing improvement. A healthy appearance, combined with a fresh skin colour have really changed the patients. They have gained about a pound a week. This is an important work to continue. When I am not busy with the house, kitchen and cooking, I must therefore use as much time as possible to be in the therapy centre. My experience is that the patients spend the time provided in the right position in their chairs to please the nurse, rather than for the benefit of their own lungs» (12.)

In its own way, this letter brings forward three important subjects focused upon by the nurses: Body weight, treatment by rest, and activities.

The increased weight of a patient confirmed one main issue. It provided a visual result of successful nursing. The increased weight of a patient came as a result of the right diet. Consequently, the nurse had to give high priority to the activities in the kitchen and at the table. The patients were usually weighed every week. Increased weight was particularly satisfactory for the owners of the institution. A report from a nurse of increased weight for the patients was a proof that the money provided by the organization gave good results. In addition, in reports of voluntary, local organisations working for the benefit of people infected with tuberculosis, one can register the pride in the fact that the organization had provided the means for buying a scale for a nurse (13.)

Daily nursing activities besides working with the patients’ diet were rarely described in «Sykepleien». Maybe it was not considered a proper issue to discuss with colleagues. The tasks were matters of routine and therefore descriptions of how to clean the spittoons, or other repulsive tasks necessary for good hygiene are not given. On the other hand, the elderly nurses of today can tell tales of when they, as young students, e.g. spent long hours lying down in the therapy centre with sick children. They were supposed to lie totally still, portraying good examples for the children. Working conditions are described in a short note in the journal, in which five nurses expressed their enthusiasm over the fact that a new sanatorium built for children had electric lights, bathroom, and water closet (14).

The need for activities for the patients has been thoroughly described in more articles in «Sykepleien». «If they had something meaningful to be interested in, we might have been spared from all the improper flirtation», a nurse complained (in translation), and she suggested the establishing of separate institutions for men and women to solve this problem (15).

Other suggestions included gathering the patients for games, and reading aloud in the evenings, as well as offering lectures on useful topics like hygiene and diet.

Several contributions discuss the importance of ergotherapy. The nurse should explain to the patients that work and exercise in fact could improve their condition. It should not be considered dangerous to use the body even when seriously sick with tuberculosis. Staff members had to explain to the patients that this therapy was to their own benefit, not because their activities were useful for the institution. If the sick could clean herself or himself and make the bed with some help, it was claimed to be a satisfaction for both body and soul. Only the fatally ill patients were allowed total rest. (16) One nurse tells her colleagues a touching story about how a patient, on his own initiative, gradually built up his own body through exercise, and thereby overcame the disease. Totally cured he could return home to his wife and small children (16). With descriptions like these the nurses encouraged each other to stimulate the patients to be active.

«Sykepleien» brought many articles which show nurses with a great involvement and creativity, trying to find good activities for the patients. Two of them from 1939, presented by a French-Norwegian nurse, Marcella Fuglesang, is worth mentioning. Her experience was to be the first social nurse at Champcueil, a public sanatorium for nearly 600 men with tuberculosis 50 km outside of Paris. Nurse Fuglesang had a special task – to create a surrounding where the patients were less inclined to leave and thereby get more out of their stay. Many of the patients had had social problems before arriving at the sanatorium. Some were immigrants from other parts of Europe or North-Africa. Because of that, her first activity was to offer the patients who did not master French a language course. Teachers were found among the other patients.

There was always someone who had special and useful skills they could teach to the other patients. A sailor, who had spent time in the docks of New York, was her first English teacher. Later she found others that were better qualified. Courses like in stenography, book-binding, and gardening were offered to patients who were interested. Those with cultural interests started both an orchestra and a theatre group. The chief physician, who initially had objections against hiring a social nurse, become enthusiastic and supported her work (17). The author herself seems to eradiate her enthusiasm out to her surroundings. Even more important, she must have offered great inspiration to her colleagues in finding new and meaningful activities for the patients.

Christmas celebration in a tuberculosis nursing home. (Private photo ca. 1924)

The nurse had to take part in the patients’ meals. (Private photo ca. 1924)

To develop competence

The communicating of knowledge was an important aim in the fight against infectious diseases. An article from 1914 emphasises that this was a task for the educated nurses. The nurses had experience from theory and practice in treating infectious diseases. The nurses had to be prepared to meet patients with tuberculosis everywhere. In the psychiatric hospitals as many as 10<[FO]>% of the patients could be infected and the male staff in such hospitals often were negligent in their hygienic protocol (18). Even though the article does not discuss this matter any further, other sources show that the nurses in the psychiatric institutions were mainly uneducated men (4). Therefore this article may be understood as a recommendation from the trade union to employ educated female nurses at the psychiatric institutions. Only one institution in Norway educated male nurses in the interwar years, and this was not sufficient to cover the need for educated personnel in psychiatry and other medical areas (19, 20, 21).

The fight against tuberculosis challenged the nurses in many ways. Here from a summer holiday camp for children with tuberculous parents. (Private photo ca. 1925)

A class of new nurses from a nursing school belonging to Norske Kvinners Sanitetsforening. (Private photo ca. 1920)

The quality of the education for nurses was a major concern for the leaders of Norsk Sykepleierforbund in this period and they demanded a three year curriculum for nursing students. The students were to have 30 theoretical lectures about hygiene in general and 30 lectures about epidemic diseases, with emphasis on tuberculosis. In addition they should spend three to four months in general epidemic wards or in wards for tuberculosis.

Consequently, we learn that these topics covered a major part of a curriculum approved by the organisation. Unless the nurse had an education approved by Norsk Sykepleierforbund, membership was not granted, and without a membership it could be hard to find work as a nurse. In this way the union had an important influence on nursing education at that time (4).

It is not surprising that the organisation of nurses emphasized the importance of knowledge of the epidemic diseases which were a major health problem in those days. Bergljot Larsson, the nursing leader, had carried out postgraduate studies in nursing of people with epidemic diseases in Scotland in 1910 (7). The board of the organization offered several scholarships to nurses who studied the subject abroad.

Standard nursing knowledge was important. However, managing skills were also particularly important if the nurses were to be leaders of an institution.

The patients with tuberculosis were treated in separate institutions. The intention was to accommodate patients undergoing treatment, and with a positive prognosis, in special wards in the hospitals or in sanatoriums. (22) The sanatoriums were often big, had beautiful surroundings and were owned by humanitarian organisations. On the other hand, small nursing homes were located throughout the country, and were often owned by someone who did not have much money to invest in them. Many of the patients placed in those homes were incurable and needed help and much nursing. Several articles in the journal in the years 1915 through 1925 dealt with the life of nurses in these homes. The articles show that the institutions were understaffed. The matron could be the only educated nurse. People in general were afraid of catching the disease, and were reluctant to seek work at such institutions. The few nurses present were under a heavy pressure.

The nurses themselves described their situation as one of isolation and loneliness both socially and when performing their duties. Small institutions did not employ doctors on a permanent basis, and in rural areas the doctor might also be unavailable when a nurse needed medical advice and support. The social isolation had two reasons. It was a result of the lack of time for recreation, and that the locals feared the contagion and avoided contact with the people working in these institutions. When the nurse had limited funding and was responsible for the economy of the institution she had an additional worry. «It is not easy to celebrate a merry Christmas», wrote one nurse (in translation) «when I as a matron only have very little in the petty cash box and I am constantly worried about unknown expenses» (23).

Given experiences like these, it is not surprising that it was hard to recruit nurses for the jobs. One action taken to attract new nurses was to make a special education for matrons of small institutions. At first it was offered a short course of three weeks, which did not attract many applicants. However, when courses were structured over 11 weeks and given at wellknown sanatoriums, the initiative became much appreciated. Sometimes applicants had to wait more than a year for a place in such programmes.

The problem with too few trained nurses who wanted to work in nursing homes faded away in the 1930’s.The improved education was an obvious reason for attracting nurses to work at such places. Another reason was the mass unemployment in these years which also affected nurses (4).

Interests in scientific research

Scientific research performed by nurses is mainly a modern phenomenon in Norway. In the inter-war years only few people associated science with the work done by nurses. Therefore, it was the doctors who presented scientific research in «Sykepleien» in the period covered by this study.

E.g. a long article claimed that it had been scientifically proven that sunbathing was an effective remedy against tuberculosis. The patient was recommended to spend one hour in the sun every day most of the year. It would be of most benefit to the patient if the nurse arranged that the patient could lie totally naked in the sun. Tanning was considered as an advantage, wrote doctor W. Holmboe (1876–1949). No other reasons were given to the readers (24). With belated wisdom one can criticize the lack of documentation for the treatment. This was, however, at a time when nurses never were taught to question the statement of a doctor.

In contrast, some articles were different. Examples are papers by dr. Johannes Heimbeck (1892–1976) at Ullevål Hospital in Oslo. He wrote about where tuberculosis occurred and how it spread within the population, and pointed to the connection between housing quality and the disease. His works also presented the dispersion of tuberculosis in the different age groups and the extent of exposure to youths when they started working. It indicated that the young ones starting to work in the hospitals had a high risk of catching tuberculosis, as compared to others (25). He also presented in two articles his work about introducing the BCG vaccine in Norway. Reading his articles was especially interesting for nurses, because the doctor’s research was mainly based on systematic studies of the nursing students at Ullevål Hospital in Oslo. Here, at the biggest Norwegian nursing school of the time, one hundred students were admitted annually. The students came from different places and social groups in the country. They were therefore considered to be a representative sample of the population. Doctor Heimbeck and some other physicians had had access to all their files, health records, etc. In this way the nurses’ dormitory became a scientific laboratory for the doctors.

When performing the first tests with the BCG vaccine, the test group was composed of two civilians and three nurses who all volunteered to the experiments. Dr. Heimbeck told that these nurses got both diarrhoea and other nervous ailments because of their knowledge when waiting for the successful test result (26). Dr. Heimbeck expressed special thanks to the powerful superintendent of Ullevål Hospital, Andrea Arntzen. She had supported the doctors’ work from day one (27). Obviously she had a special understanding of the value of the doctor’s works. As the leader of the nursing school, she had had to expel students because many of them contracted tuberculosis. However, the fatal accidents with BCG vaccine in Allgemeines Krankenhaus in Lübeck in 1930 was never mentioned in «Sykepleien». (28) The knowledge of the vaccination seems only to have encouraged the nurses.

From a big sanatorium around 1917. (Private photo)

The staff of a small nursing home for patients with tuberculosis ca. 1930. (Private photo)

Commitment and creativity

It became important to the nurses to take part in the work against tuberculosis. To meet the challenges various solutions were chosen. One nurse told her colleagues that she had bought herself a motorbike. It enabled her to visit more schools than before, when she was using an ordinary bike. (29) This nurse using her motorbike is one of many proofs for the creativity and involvement nurses have shown in the fight against tuberculosis.

References:

Schiøtz, A. Folkets helse – landets styrke, 1850 – 2003. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 2004: 208.

Blom, I. Feberens ville rose, Tre omsorgssystemer i tuberkulosearbeidet 1900 – 1960. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget, 1998.

Rogstad, S. Kampen om eiendomsretten til tuberkulosesaken. Historisk Tidsskrift, 1997; 76: 87–116.

Melby, K. Kall og Kamp. Norsk Sykepleieforbunds historie. Oslo: Cappelen, 1990.

Mathisen, J. Sykepleiehistorie. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 1993.

Fause, Å. Et fag i kamp for livet, sykepleiens historie i Noreg. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget, 2001.

Hvalvik, S. Bergljot Larsson og den moderne sykepleien. Oslo: Akribe, 2005.

Bratt. JF. Retningslinjer i kampen mot tuberkulosen. Sykepleien, 1931; 10: 118–24.

Schram, T. Litt om hjælpestationer og Kristiania Sundhetskommissions tuberkulosearbeid. Sykepleien, 1920; 4: 31–5 and 42–9.

Nurse Marie Olsen. Personal Diary from Narvik 1940.

Sykepleien, 1929; 2: 45–6.

Aaraas; H. Fra et tuberkulosehjem. Sykepleien, 1915; 1: 7–8.

Records from Kirkeøy Sanitetsforening and Sarpsborg Sanitetsforening.

Arnesen, M, Thorsen J. Fra Trondhjem. Sykepleien, 1915; 7: 71–2.

Hirsch, A. Tuberkulosehjemmene og vi søstre. Sykepleien, 1918; 4: 38–9.

Finborud, L. Arbeidsterapien. Sykepleien, 1931; 4: 38–40 and 5: 52–6.

Fuglesang, M. Social-sykepleierskens arbeid i Frankrike. Sykepleien, 1939; 9: 128–33 and 10: 141–45.

Sykepleien, 1914; 3: 25–7.

Martinsen, K. Freidige og uforsagte diakonisser, et omsorgsyrke vokser fram. Oslo: Aschehoug, 1984.

Norseth, T, red. Det Norske Diakonhjem, 1890 – 1940. Oslo: Styret ved Diakonhjemmet, 1940.

Stave, G. Mannsmot og tenarsinn, Det Norske Diakonhjem i hundre år. Oslo: Samlaget, 1990.

Skogheim, D. Sanatorieliv. Fra tuberkulosens kulturhistorie. Oslo: Tiden norsk forlag, 2001.

Sykepleien, 1914; 7: 68–9.

Holmboe, W. Solbehandling av tuberkulose. Sykepleien, 1918; 3: 27–30, 6: 56–8, 7:68–9.

Heimbeck, J. Nye momenter i kampen mot tuberkulosen. Sykepleien, 1929; 2: 16–20.

Heimbeck, J. Tuberkulosevaksinasjon av Sykepleiersker. Sykepleien, 1930; 7: 73–80.

S.D. Sykepleierskene og tuberkulosen. Sykepleien, 1936; 7: 73–80.

Winkle, S. Kulturgeschichte der Seuchen, Düsseldorf: Artemis & Winkler, 1997, p. 148.

Kristiansen, O. R. Helsesøster på landet. Sykepleien, 1938; 9: 121–2.

Associate professor, Østfold University College,

Faculty of Health and Social Studies,

Pb. 1409,

N-1602 Fredrikstad, Norway,

e-mail: Jorunn.Mathisen@hiof.no

Military medicine in paintings (1)

Rodrigo Moynihan RA CBE (1910–1990): «Medical Inspection 1943». (Oil on canvas. Imperial War Museum, London. Photo: Ø. Larsen 1999.)

Military medicine in paintings (2)

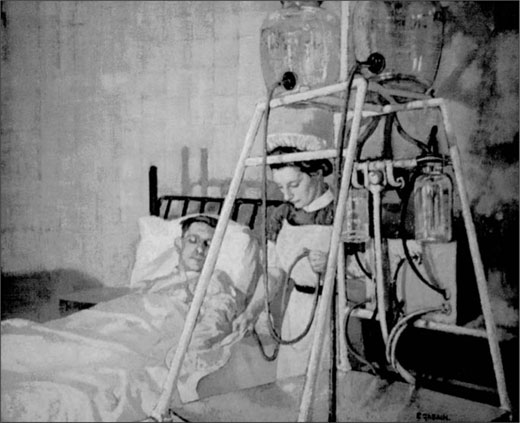

Ethel Gabain (1882–1950): «A Bunyan-Stannard Irrigation Envelope for the Treatment of Burns». (Undated. Oil on canvas. Imperial War Museum, London. Photo: Ø. Larsen 1999.)