Sick Finland? – The crisis of Finnish health policy in the 1960s

Michael 2004; 1: 287–99.

Introduction

A basic target for health policy [is] staying alive. In Finland this target is poorly reached. 1 Our health care proves to be peculiarly backward We stick out sharply from the other Nordic countries and mostly join the poorest nations of our continent. 2

(…) how and why do the healthiest babies in the world grow up into the sickest adults in Europe? 3

The achievements of Finnish health policy were subjected to severe criticism in the 1960s and 1970s. The basis for and the focus of post-war health policy were rigorously questioned by both public authorities and experts. It was even provocatively argued that as a result of the unsuccessful policy the entire nation was sick.4 However, as late as the 1950s, the health policy of the twentieth century was considered to be a great success in Finland: mortality rates declined, contagious diseases were brought under control and tuberculosis was gradually beaten.5 How is it possible that the views on Finnish health policy changed dramatically in a single decade?

This article examines the origins of the health policy crisis of the 1960s in Finland and its contributory factors. The crisis launched an extensive debate on the means, goals, content and possibilities of health policy. Presumably, changing definitions of health and health indicators, as well as health risks, played a significant role in the crisis. Studying a period during which the direction and form of health policy were reformulated, makes it possible to analyse the conditions, consistencies and changes in health policy in general.

Finland is characterised by the central position of government in health policy. In other words, health services are organised and supervised by the government, and even voluntary organisations work in close relationship with the government.6 Therefore, my focus is on official health policy, which was organised by the state and the municipalities and led by the National Board of Health. The main sources consist of the documents of the National Board of Health. Additionally, the study is based on an analysis of the health debate in national medical journals and public health literature.

Finland in the 1960s was transformed by a rapid change from an agrarian country to an industrialised and urbanised one. This entailed internal migration and emigration, rising living standards, changing living conditions and ways of life, increasing free time, and breaks in social patterns and traditions.7 The structural change of society, which, compared to other Scandinavian countries, was notably delayed, provides a societal frame for analysing the field of health policy.

The crisis

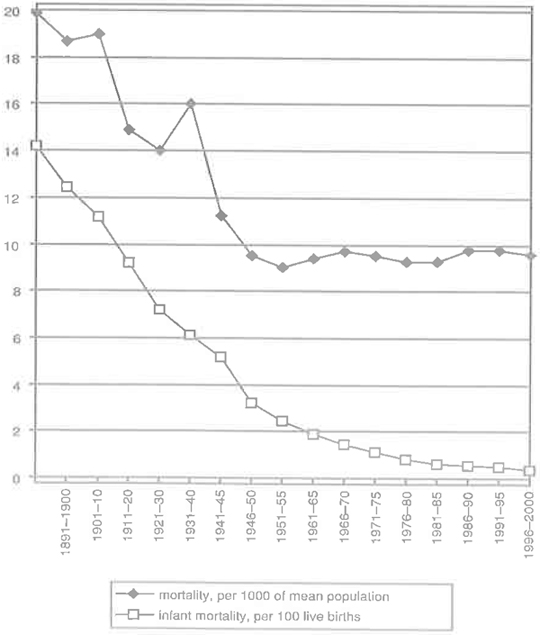

As the development of mortality was considered the most unambiguous indicator of the success of health policy, a remarkable feature in Finland in the 1960s was the rise of mortality rates (Fig. 1). During the twentieth century the mortality rates had been constantly declining and the only in- creases had occurred during the Civil War of 1918 and during the Second World War in the early 1940s. Therefore, a rise during peacetime was an exceptional situation.

Fig. 1. Mortality and infant mortality in Finland 1891–2000

Sources: Statistical Yearbook of Finland 2002, p. 125, 144; Suomen väesrö, (1994), p. 323; http://www.stm.fi/kvt/suomi/ykhuippumaaliite1.htm#Liite %202

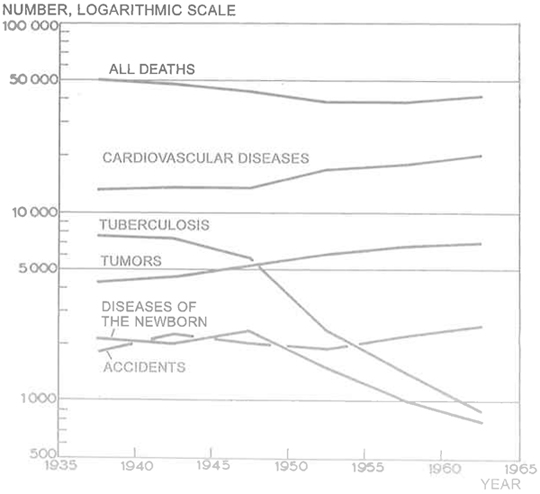

Additionally, the statistics showed that it was no longer acute epidemic diseases, tuberculosis or diseases of newborn children which brought the Finns to their graves. The favourable development in infant mortality especially was a source of national pride (Fig. 1.).8 Instead, the increased incidence of new fatal diseases – cardiovascular diseases and cancer – was evident. (Fig. 2.) Beating this novel, chronic major diseases – in Finnish kansantaudit meaning people’s diseases or national diseases – became a new concern for the authorities.

Fig 2. Main causes of death in Finland in 1936–65

Source: L. Noro, Sosiaalilääketieteen perusteet 1968, p. 61.

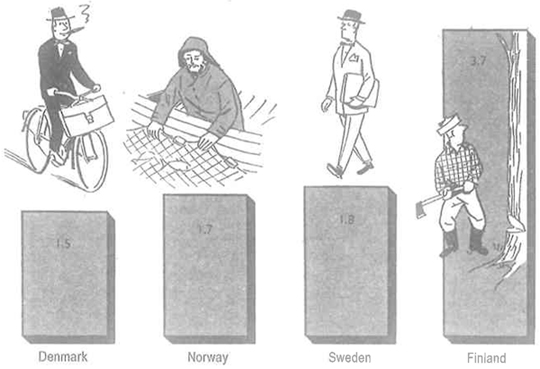

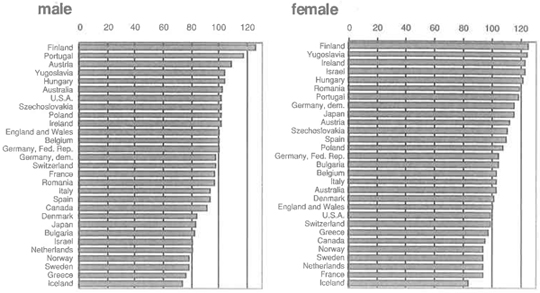

The statistics showed that Finnish men especially died prematurely: the mortality among Finnish men was observed to be twice as high as in other Scandinavian countries (Fig. 3). Accordingly, the result of a comparison among 29 countries in 1965 was even more shocking, for Europe’s highest death rates were found in Finland. (Fig. 4.) It was even stated that for a 40- year-old man the situation was worse in Finland than it was in Costa Rica or Albania. This fact was considered to be a national disgrace: how was it possible that our country had failed in the basic task of keeping its citizens alive? How was it possible that the healthiest babies grew up to be the sickest adults?9

Fig. 3. Mortality of 35–39-year-old men in the Scandinavian countries in 1956, per 1000.

Source: Kuusi, P., 60-luvun sosiaalipolitiikka (1961), p. 263.

Fig. 4. Standardised mortality as index in selected countries in 1965 (England and Wales = 100)

Source: Official Statistics of Finland XI: 70–71 1967–68, p. 26.

Since the late nineteenth century – and especially since independence in 1917 – health policy was seen a part of the nation-state building project in Finland. While being a part of the civilized word and keeping up with the development of the Western Europe had become a central goal, falling into the same category with developing, poor countries was considered a national and cultural crisis.10 The crisis was also a demographic and an economic one, as the nation lost a substantial number of citizens in their prime, which also meant a huge loss of workforce.11

In addition to that, the crisis in health policy had a regional aspect. The expectation of life of a newborn baby boy was found to be three years shorter in Eastern Finland than in Western Finland. The situation pointed to the conclusion that there had to be serious regional inequalities in health and health services in Finland.12 As democracy, social equality and economic growth were seen as tightly interrelated factors in the development of modern society in the 1960s, so also inequalities in health were considered to be both morally unacceptable and economically detrimental.13

Emphasis on population policy – a delayed reaction

The unpreparedness for the changing mortality and health patterns in Finland can partly be explained by a lack of comparative statistics. Detailed analyses of the causes of death only became possible in Finland in 1936, when the statistics were based on medical certificates and were brought into line with international statistics.14 The first introductory studies based on these statistics were published in the late 1940s and 1950s.15

However, a more substantial factor in the process seems to be the fact that Finnish post-war health policy strongly emphasized population policy, which gave priority to children’s and mothers’ health. A municipal system of maternity and child welfare clinics was built up in the 1940s. Furthermore, preventive health care services and social policy were successfully combined: in order to be eligible for maternity allowance pregnant women had to attend the maternity clinic.16

Concentration on children meant, on the other hand, that the need for health care for other age groups was overlooked. Although the new Finnish term for public health, kansanterveys – which became common in the 1930s and 1940s as an equivalent to the Swedish term folkhälsa, literally meaning people’s health17 – suggested as its scope the whole nation regardless, for example, of age or gender, it was particularly the care for mothers and children which was defined as a matter crucial to the survival of the nation. It was, for example, explicitly stated that chronic diseases were population politically irrelevant, because those who suffered from these diseases were usually old people.18 Besides, there was no tradition in health policy for coping with chronic non-contagious diseases, as ever since the late nineteenth century, health policy interest had been based on hygienic thinking and focused on suppressing acute epidemics.19

Health services as a solution

The discourse of health policy changed in the early 1960s and the emphasis on children and mothers was replaced by a concern for adult Finns. The Public Health Committee, which was appointed in 1960, stated that death rates clearly showed the preferential status of young age groups within health care services. Now it was necessary also to include the older citizens in the sphere of health care. All Finnish people became the target group of health policy.20

To guarantee a sufficient supply of health services became the main goal. In Social Policy for the Sixties, a seminal work guiding the development of Finnish society in the 1960s and 1970s, it was argued: ‘The growth of the supply of medical services as such will nowadays usually guarantee an improvement in the health of the nation’.21

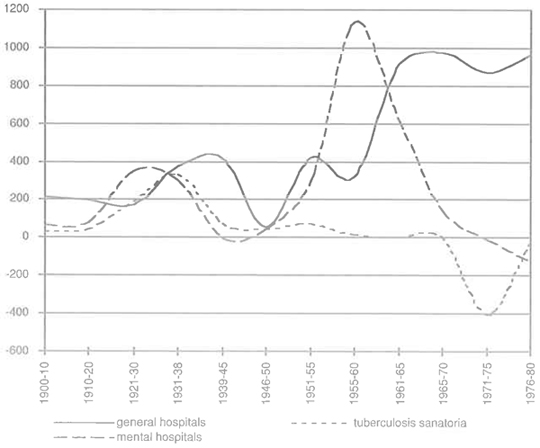

International comparisons did indeed show that Finland had fallen behind in health service development: the number of medical staff per capita was the lowest in Europe and the number of hospital beds was below the average European standard.22 The need for medical doctors was gradually met by creating new training arrangements in Finland and abroad.23 After a massive building project of general and mental hospitals, which can be seen in Fig. 5, Finland reached the top of the world in the number of hospital beds in the late 1960s. In contrast to the other hospital sectors, the separate tuberculosis sanatoria could gradually be closed down as the morbidity from tuberculosis declined, and the sanatoria could be used for patients suffering from other diseases.

In addition to the urge to offer every citizen everywhere in the country equal access to health services, another goal was to remove the financial barriers to using the services. People’s slowness in seeking medical care as well as the plenitude of untreated diseases was seen as the results of inadequate compensation for medical costs.24 Nationwide sickness insurance was finally put into practice in 1964, after a discussion of no less than 50 years. In the name of equality between the rural and urban population, the insurance was not restricted to wage earners but extended to all Finns, which meant a significant step in creating a comprehensive system of social welfare in the country.25

Fig. 5. Changes in number of hospital beds 1900–1980, annual means

Sources: Vauhkonen 1961, p. 50; Official Statistics of Finland XI: 72–73 1969–70, p. 228, 244; Official Statistics of Finland XI: 78 1982, p. 178.

Despite these reforms the situation was not, however, considered satisfactory. The building of hospitals consumed most of the public resources put into health services. Due to the rapid technical development the costs rose unforesceably. Besides, it was noticed that elderly and chronic patients occupied most of the hospital beds, and waiting lists were long.26 The results and efficiency of the hospital-based system were called into question. ‘People’s health doesn’t conclusively improve by the mere fact that good doctors cure bad patients in modern hospitals’, it was argued.27

Outpatient care and preventive care were declared the new solution to the cost crisis of the hospital-based service system in the late 1960s. In fact, the importance and economic efficiency of preventive health care was already clearly stated in the health policy plans of the 1940s and the positive results of maternity and child welfare clinics could be seen as irrefutable proof of the benefits of preventive care.28 With the passing of new Public Health Act in 1972, the local practices of municipal medical officers and public health nurses were replaced by an extensive municipal health centre system. The idea was to prevent disease by medical checkups and health education. It was hoped that the social differences in the use of health services would disappear with efficient cost-free primary health care.29

The growing supply of health services raised the question of how to motivate people to use the services. On the one hand it was argued that fostering health was a part of human nature and no extra incentive was needed. On the other hand it was even suggested that sickness insurance would only be paid on condition that the person attended regular health checkups.30 The latter idea, which perceived it as the obligation of individuals to avail themselves of services provided by the state in the interest of safeguarding the health of the nation rather than respecting the autonomy of the individual, was introduced in the maternity services of the 1940s.31 However, in the 1960s the idea of shepherding the uneducated public did not concur with the emerging discussion on the rights of the individual in social and health policy.32

Social development policy: Health policy as a part of social policy

A new wave a criticism emerged in the late 1960s. The critics now argued that investments in health services would no longer improve the health of the nation. Until then, the rising standard of living had furthered the efforts of health policy, but now economic growth was perceived to result in new ‘welfare diseases’. Because it was society itself that caused diseases, it was society that should be changed. Therefore, health policy, which only concentrated on health services and operated in isolation from other sectors of society, was considered useless. It was underlined that, instead of health services, it would be more rational to invest in other sectors of society. In other words, health should become a decisive argument, for example, in housing policy, environmental policy and taxation policy. In summary, health policy had to be a part of social development policy.33

The new discourse on health policy related to the cultural and political radicalism of the late 1960s. Even the health administration experienced a change to a new, radical generation.34 In addition, the criticism reflected the powerlessness of medicine to treat the new people’s diseases. ‘We have to admit that the ways to beat (…) the people’s diseases are not adequately known’, stated the annual report of National Board of Health in 1969–70.35 As the epidemiological profile had changed, instead of microbes new complicated factors, which were closely linked to people’s social environment, were found to cause diseases.36 Besides medicine, social sciences gained ground in defining health. The mortality rate as such was considered an inadequate measure of health, because it ignored many significant diseases – for example mental illness, rheumatic disease – and failed to consider the social aspects of health.37

This new emphasis on the social nature of health contributed to administrative changes: the health administration was transferred from the Ministry of the Interior to a new governing body, the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health.38 Another significant reform was the creation of a permanent statutory planning system in 1972. Instead of temporary and case specific committee-based planning, Finnish health policy became based on regular five-year plans.39

One of the main achievements of the new health policy was new legislation on occupational safety (1973) and on the restrictions on smoking (1976).40 Among these structural, macro level measures an indicator of new; more individually based approach to health was the launching of the North Karelia Project (1972), which aimed at reducing cardiovascular diseases by interventions in lifestyles.41 Hypotheses were evinced that the high mortality was attributable to detrimental smoking and eating habits rather than factors such as the harmful effects of the Second World War, occupational structure and low standard of living. Nevertheless, the researchers admitted that the exceptional mortality rates remained essentially a mystery.42

Conclusion

The crisis of Finnish health policy in the 1960s was a reflection of a change in a successful health care development lasting half a century. Statistics and international comparisons had a crucial meaning in the crisis, showing the trend from success to failure. The rise of mortality rates and the excess mortality of Finnish men especially, gave rise to claims about the erroneousness and backwardness of the health policy.

A basic factor in the crisis was the changing definition of health and health risks. Beside acute, fatal, infectious diseases, chronic diseases were also brought into the focus of health policy. A new emphasis on preventing diseases gradually gained ground, and in the late 1960s, health was defined as a broad concept connected to society.

In practice, the focus of health policy of the 1960s changed from the building of hospitals to primary health care and preventive health care and finally to the structural development of society to be more conducive to good health. Considering the role of individuals versus society, the health service policy of the early 1960s was distinctively system-orientated: people’s lifestyles and living conditions became invisible and people were perceived as passive users of the services. During the late 1960s and 1970s the emphasis on socio-economic structures contributed to recognition of the importance of living conditions to health. Subsequently, promoting healthy lifestyles and underlining the ideas of individual freedom and responsibility for one’s health became key concepts in the health policy discourse of the 1980s and especially after the severe economic crisis of the 1990s.

Placing the crisis of the 1960s in the context of Finnish health policy development of the twentieth century shows that it was not an isolated phenomenon. Throughout the century, Finnish health policy can be outlined as a chain of health projects, which have consisted of changing views on health, health risks, as well as measures and conditions to maintain and achieve good health. Judged from each new point of view the achievements of the health policy of previous periods have seemed to be inadequate. During the 1960s, the ideas of hygiene and population policy, which date from the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, were considered inappropriate to modern challenges and replaced by new projects focusing on the health service system and health policy as a part of social development policy. What was exceptional for the 1960s was the intensity of the debate, which can be explained by the simultaneous rapid changes in the epidemiology, demography and society.

Finland: Waning welfare? (Helsinki 1997, photo: Ø. Larsen)

Helsinki 1997. (Photo: Ø. Larsen)

References

K. Leppo and K. Puro, ‘Sairas Suomi’ [Sick Finland]. Yhteiskuntasuunnittelu 2 (1972), p. 5. Quotation translated by M.H.

P. Kuusi, 60-luvun sosiaalipolitiikka (Helsinki 1961), p. 257. Quotation translated by M.H. An abbreviated English edition of Kuusi’s book Social Policy for the Sixties was published in 1964.

Official Statistics of Finland Xl: 72–73 1969–70, p. 87. Quotation translated by M.H.

K. Leppo and K. Puro, ‘Sairas Suomi’ [Sick Finland]. Yhteiskuntasuunnittelu 2 (1972), 3–7.

For example: Official Statistics of Finland Xl: 58 1955; Official Statistics of Finland Xl: 62 1959.

A. Anttonen and J. Sipilä, Suomalaista sosiaalipolitiikkaa [Finnish Social Policy] (Tampere 2000), pp. 12–13.

H. Waris, Muuttuva suomalainen yhteiskunta [Changing Finnish Society] (Porvoo 1968).

Compared with the infant mortality rates in other European counties Finland was ranked seventh in 1956. In the late 1960s Finland was among the three leading countries in the world. Kuusi, 60-luvun sosiaalipolitiikka, p. 256, 261; Leppo and Puro, ‘Sairas Suomi’, p. 3–5.

Kuusi, 60-luvun sosiaalipolitiikka, pp. 256, 262–3; Leppo and Puro, ‘Sairas Suomi’, pp. 3–5; Official Statistics of Finland Xl: 70–71 1967–68, p. 26.

On the meaning of foreign models in the hygienic health projects in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century, see for instance M. Hietala, ‘Hygienian ja terveydenhuollon eturintamaan ulkomaisten yhteyksien avulla’ [Into the Vanguard of Hygiene and Health Care with Foreign Connections], in Tietoa, taitoa asiantuntemusta I (Helsinki 1992), 67–206; M. Harjula, Tehdaskaupungin takapihat. Ympäristö ja terveys Tampereella 1880–1939 [Backyards of Factory Town. Environment and Health in Tampere 1880–1939] (Tampere 2003).

For example: Leppo & Puro, ‘Sairas Suomi’.

Official Statistics of Finland Xl: 64 1961, p. 15; Leppo and Puro, ‘Sairas Suomi’, p. 4.

Kuusi, 60-luvun sosiaalipolitiikka.

S. Koskinen and T. Martelin, ‘Kuolleisuus’ [Mortality]. In Suomen väestö (Helsinki 1994), pp. 162, 165.

For example: V. Kannisto, ‘Mikä lyhentää elinaikaamme?’ [What shortens our lifetime]. Kansantaloudellinen aikakauskirja (1945); J. Kihlberg and L. Noro, ‘Eri syiden Suomessa vv. 1946–50 aiheuttama kuolemanvaara’ [The risk of death caused by different causes in Finland 1946–50]. Duodecim (1955).

A detailed study on maternity services: S. Wrede, Decentering Care for Mothers: The Politics of Midwifery and the Design of Finnish Maternity Services (Åbo 2001).

K. Johannisson, ‘The People’s Health: Public Health Policies in Sweden’, in D. Porter (ed.), The History of Public Health and the Modern State (Amsterdam 1994), 165–82.

S. Savonen, ‘Kansanterveystyö väestöpoliittisena tekijänä’ [Public Health Work as a Population Political Factor]. Suomen Lääkäriliiton Aikakauskirja 2 (1942), p. 53.

Harjula, Tehdaskaupungin takapihat; Hietala, ‘Hygienian ja terveydenhuollon eturintamaan ulkomaisten yhteyksien avulla’.

Komiteanmietintö 1965: B 72. Kansanterveyskomitean mietintö [Public Health Commitee Report] 1965, p. 6, 8, 31.

Kuusi, 60-luvun sosiaalipolitiikka, p. 254.

Kuusi, 60-luvun sosiaalipolitiikka, pp. 256–61.

N. Pesonen, Terveyden puolesta – sairautta vastaan. [For Health – Against Sickness]. Porvoo 1980, pp. 667–9.

Kuusi, 60-Iuvun sosiaalipolitiikka, pp. 274–5.

K. Urponen, ‘Huoltoyhteiskunnasta hyvinvointivaltioon’, in J. Jaakkola, P. Pulma, M. Satka and K. Urponen, Armeliaisuus, yhteisöapu, sosiaaliturva. Suomalaisten sosiaalisen turvan historia. [Charity, Communal Aid, Social Security. The History of Social Security of the Finns] (Helsinki 1994), pp. 237–8.

Kuusi, 60-Iuvun sosiaalipolitiikka, pp. 260–1; H. Simola, Sairaalalaitoksen kehitys Suomessa sodanjälkeisenä aikana [The Development of Hospitals in Finland after War] Sosiaalinen Aikakauskirja 6 (1972); Komiteanmietintö 1971: B 4. Terveydenhuollon suunnittelukomitean mietintö [Report of the Planning Committee of Health Care], pp. 1, 54–60.

Kuusi, 60-Iuvun sosiaalipolitiikka, p. 274. Quotation translated by M.H.

S. Savonen, Kansanterveystyötä tehostamaan! Maalaiskuntien yleisen terveydenhoidon ohjekma [Let’s intensify public health work! The Program for General Health Services in Rural Municipalities] (Helsinki 1941), p. 10; Kuusi, 60-luvun sosiaalipolitiikka, p. 274.

Kansanterveyslaki 66/1972 [Public Health Act]. Health centre charges were gradually removed by the end of 1979. J. Aer (ed.), Kansanterveystyön käsikirja [Handbook of Public Health] (Helsinki 1975), p. 115.

Kuusi, 60-Iuvun sosiaalipolitiikka, pp. 276, 284.

Wrede, Decentering Care for Mothers, p. 256.

Suonoja, ‘Huoltoyhteiskunnasta hyvinvointivaltioon’, pp. 241–2; M. Satka, ‘Sosiaalinen työ peräänkatsojamiehestä hoivayrittäjäksi’ in J. Jaakkola, P. Pulma, M. Satka and K. Urponen, Armeliaisuus, yhteisöapu, sosiaaliturva. Suomalaisten sosiaalisen turvan historia. [Charity, Communal Aid, Social Security. The History of Social Security of the Finns] (Helsinki 1994) pp. 303–5.

Puro and Leppo, ‘Sairas Suomi’, pp. 6–7; ‘Kansanterveyslain synty’ [The Making of Public Health Act]. Yhteiskuntasuunnittelu 2 (1972), p. 10; K. Puro, Terveyspolitiikan perusteet [The Basis for Health Policy] (Helsinki 1974).

Wrede, Decentering Care for Mothers, p. 175.

Official Statistics of Finland Xl: 72–73 1969–70, p. 21. Quotation translated by M.H.

Puro, Terveyspolitiikan perusteet, pp. 12–13; Elämisen laatu Yhteiskuntapolitiikan tavoitteita ja niiden mittaamista tutkiva jaosto. Liite 1. Terveyspolitiikan tavoitteita tutkivan työryhmän raportti [Quality of Life. Section for Studying and Measuring the Goals of Social Policy] 1972, pp. 20–8.

Komiteanmietintö 1971: A 25. Sosiaalihuollon periaatekomitea [Commitee Report. The Commitee for the Basis of Social Welfare] p. 29; Puro, Terveyspolitiikan perusteet, pp. 49–55.

P. Haatanen and K. Suonoja, Suuriruhtinaskunnasta byvinvointivatioon: Sociaali-ja terveysministeriö 75 vuotta [From Grand Duchy to Welfare State: Ministry of Social Affairs and Health 75 Years) (Helsinki 1992), pp. 484–5.

Aer (ed), Kansanterveystyön käsikirja, pp. 119–42. On the need for planning: Komiteanmietintö 1971: B4, pp. 85–143.

Terveyttä kaikille vuoteen 2000: Suomen terveyspolitiikan pitkän aikavälin tavoite- ja toimenpideohjelma. [Health for All by the Year 2000: the Finnish National Strategy] (Helsinki 1986), p. 20.

P. Puska et al. (eds), The North Karelia Project: 20 Year Results and Experience (Helsinki 1995).

For example: P. Piepponen and M. Ritamies, Miesten ylikuolleisuus Suomessa. [The Excess Mortality of Men in Finland]. Väestöpoliittisen tutkimuslaitoksen julkaisuja. Sarja B (Helsinki 1966); T. Valkonen, ‘The Mystery of the Premature Mortality of Finnish Men’ in R. Alapuro et al. (eds), Small States in Comparative Perspective (Oslo 1985), 228–241.

Ph.D., researcher

Department of History

33014 University of Tampere

Finland

Fax: +358 3 215 6980

e-mail: minna.harjula@uta.fi