Electrical safety administration as an intermediate form of private and public operation

Michael 2004; 1: 301–14.

Introduction

The governance of electrical safety means a combination of regulations, procedures, and practices for organizing and managing surveillance within the field. It is also a question of organizational solutions and cooperation arrangements that have been affecting the administration of electrical safety. Governance is based on an administrative model put forth in the regulations and norms of the field, including both legislation and standards. Governance entails the factors guiding the operations, which should implement the principle of good governance (see e.g. Aarrevaara 2001, 11–12). By public regulation we mean the different sets of norms stipulated and controlled by the public authority.

Research on administration focuses on the regulations and processes, and the behaviour of authorities. The objective of the development of governance is good governance that is responsible and effective. Good governance may produce economic results but, above all, it produces trust and authority in the citizens’ eyes, and promotes the effectiveness of the operation. This paper describes how electrical safety administration has evolved in Finland. We also present our estimate of its effectiveness. The paper is based on document and interview material gathered during 2002.

By the governance of electrical safety we mean the combination of regulations, procedures, and practices used for organizing and managing surveillance within the field. It is also a question of organizational solutions and cooperation arrangements that have been affecting electrical safety governance in Finland. Governance concentrates on regulations, processes, and the behaviour of authorities.

The central objective of our paper is, however, to explain the development and the current situation in electrical safety. Our work has involved studying the main turning points in electrical safety and the search for an explanation to their emergence.

Social capital in the governance is particularly manifested in trust and reciprocity. On the basis of our material it is fair to say that it has proven a methodologically challenging task to identify the trust and reciprocity related to the networks, operators, operations, and reciprocal relations concerning social capital (see. Stenvall 2001). For instance, when drawing up documents and plans, good administrative practices often include the principle that they do not bring forth contradicting arguments and compromises made in the spirit of reciprocity. Until mid-1950s, the operating culture within the field was such that even severely conflicting arguments were not shown outwards and all presentations were made in unison. The interpreting and identifying of social capital in the administrative practices is, indeed, one of the central requirements of our paper.

Intermediate form of public and private organization

What is particularly exceptional in the history of the administrative model of Finnish electrical safety is that the electrical safety authority has been based on an association model. The system was in use over a period of almost 70 years, from 1928 to 1995, after which the administrative model was incorporated with the government administration by establishing a government office, the Safety Technology Authority (Turvatekniikan keskus, TUKES) and transferring the tasks of the earlier association-based organization under its authority.

The active juvenile phase in the promotion of the electrical safety system starts with the establishing of Inspection Centre for Electrical Installations (Sähkötarkastuslaitos) and continues to the 1960s. The phase of maturity stretches from the 1960s to 1985, when criticism towards the system begins to increase. The system lived its declining phase from mid-1980s to mid-1990s, when many of the central operators within the field failed to see the need for change. It was difficult to let go of the long-established system in which so many individuals had made great personal efforts for creating and developing the system.

The association-based system has included numerous unique features. The responsibility for electrical safety was largely carried by the operators within the field. At the same time, the administrative model meant that the surveyed companies and other operators had the possibility to control the contents of surveillance. However, there was no public criticism against the administrative model questioning the ethics of its operation.

A strong network of associations, companies, and the surveying authorities has prevailed within the field of electrical safety, and this explains the development of the administrative model. In electrical safety, social capital is a force comparable to institutions, maintaining continuity and explaining the established practices and solutions.

The authority of the association-based electrical inspection institution Inspection Centre for Electrical Installations was extensive especially after 1957 when the ministry enforced their right to issue binding application instructions.

Typically, changes in regulations and organization have especially caused crises in the discussion within electrical safety governance. The threats have not materialized. However, on the basis of our material, at least the changes in the governance made so far have actually improved rather than deteriorated electrical safety. Discussions on electrical safety were lively in conjunction with the transfer to market control in mid-1990s. In this respect it can also be said that the threats have not been put forth.

With Finland’s EU membership the electrical safety administration model became merged with the international system. It should be noted, however, that from the point of administration even more important than EU membership was the EEA agreement. Through regulations it defined, for instance, the conditions of entering the market in a way that ended the system based on preliminary inspections. The changes in governmental regulation and operating principles have been adopted almost as such among those working within electrical safety governance, without any significant changes in social relations. For instance, the stricter regulations introduced in the 1980s were primarily considered an existing fact. The Finnish electrical safety governance is not a passive, receiving party in the EU system. It participates in the development of directives, but also affects other member states through the example of its organizational solutions.

The EEA agreement defined the introduction of products to the market of the area. Free movement of products within the market was allowed after ensuring their conformity to the requirements through initial inspection that is the manufacturer’s responsibility. The system is based on initial inspection of products and on market control as well as control of use and conditions. The starting point of the EU system is that due to effective initial inspections there are only safe products on the market. Initial inspection requires, however, complementary operations. Therefore, the authorities have been secured the possibility to intervene in case of such safety risks that have not been possible to foresee in the manufacturing stage.

Some product risks are not revealed until the product has been in use for some time. The products conforming to the requirements of the Community can be identified by the CE label attached to them by the manufacturer (TETAKO 1992, 24–25). The CE label does not, however, offer information for the consumer but for the authorities. It is the manufacturer’s indication that the product meets the EU requirements.

Segregated control responsibility

In the EU system, initial inspections are carried out by independent institutions notified by the states, and their actual technical inspection operations are open to competition. The government is responsible for the competence of the notified institutions, and this can be verified using, for instance, accreditation. Thus, the inspecting institutions can be public or private. In Finland, the development of technical infrastructure belongs to the Ministry of Trade and Industry (vnp 3.12.1992). These include calibration and metrology systems, test laboratories, inspection and certification institutions, and systems for verifying competence. The basic systems are complemented by technical standards.

Market control, on the other hand, means the procedures used by authorities for supervising the operation of initial inspections through examining products that already are on the market. Preventing the access and movement of non-conforming products on the market is in the EU system the responsibility of the member states that nationally organize the authority for market control.

With the responsibility of initial inspections transferred to the manufacturers, the role of the authorities in market control is emphasized. The responsibility for market control is, thus, with the authorities, but market surveillance is also participated by, for instance, the competitors, citizens’ organizations, and customers. In Finland the system for market control had to be created by the time the EEA agreement came into force, i.e. by 1994.

In market control the authority plays a central role in building up the consumers’ confidence in products. This did not call so much for a tight decision-making system based on interaction and social capital but more so a control system that is functional, independent, and reveals deficiencies. During 1994, the market control system was started off by making about 3000 business visits and actively informing the consumers. Being a new EU member state Finland was a pioneer in market control practices. The Finnish system was not directly based on the system of any other member state.

The control of use and conditions means all other surveillance included in technical inspection operations except product control. It is directed to installations, working and environmental conditions and use, as well as the pursuit of operations. The control of use and conditions is a task for the authorities and it includes technical inspections that can be transferred to public or private inspection and test institutions with verified competence (TETAKO 1991, 3).

Segregating commercial and authoritative tasks

The Finnish Government concluded in 1992 a decision of intent that the authoritative tasks and the technical inspections and testing shall be segregated. Technical tasks can, according to the committee, be limited to operations that are presupposed in regulations or decrees. These include approvals and inspections for ensuring the products’ conformity to the requirements or for implementing the control of use in different production processes and machineries. A company or institution carrying out technical tasks may act as a ‘third party’, and is not using public authority. This enables the user of services to decide, which of the companies or institutions with verified competence they will choose.

Authoritative tasks, on the other hand, have always been stipulated by laws in Finland. These tasks are ordered to be carried out by an organization, and the authority cannot transfer any tasks to a third party. An organization carrying out authoritative tasks is using public authority, and it possesses the necessary authority and coercive means. Also the fees they collect are based on stipulated regulations.

An administrative procedure enforced by law is followed in authoritative tasks. The objective is that the citizens’ rights and obligations will in the decision-making of the administrative authority be given the form intended in the law. Authoritative operations may be given other kinds of requirements regarding the gathering of information needed for decision making, ensuring impartial handling, and implementing the service principle. (Cf. e.g. Syrjänen 1996, 147–148).

Regarding Inspection Centre for Electrical Apparatus (SETI), the committee delegated to review the case defined their authoritative tasks as follows: preparation and issuance of norms, control of use regarding the holders of electric machineries and elevators, surveillance of the installation inspections by electricity boards, granting of qualification certificates to supervisors of electric work and use, and market control. Furthermore, it defined SETI’s authoritative tasks to include the granting and revoking of certain permits to electric designers as well as electric and elevator contractors, as well as the surveillance of contracting and the maintenance of registers.

The technical tasks are significantly different. Several companies and institutions may have the required competence and it is usually verified by accreditation or certification. This enables competition in the implementation of technical tasks. The supplier of services may be a private or a public institution, and they set the prices of their services independently.

A committee defined the technical tasks of SETI to include the commissioning inspections of electric and elevator contractors, the periodic inspections of the holders of electric machineries and elevators, the testing, certification, and type inspections of electric appliances, as well as the inspection of lifting devices and ski lifts.

Angle of view shifting from safety to efficiency

A law that came into force early in 1902 presupposed that «electric plants operating with electric current of so high voltage or otherwise of such quality, or being located in a such a place that the plant may cause danger to life or property, shall be provided with special surveillance» (translation). In the current laws on electrical safety from 1966, the same objective is expressed so that» electric appliances and machineries shall be designed, constructed, manufactured, and repaired, and they shall be maintained and used in such a way that they do not cause danger to anybody’s life, health, or property» (translation).

After the Second World War industrialization was rapid in Finland. An indication of this is that the volume of industrial production in Finland grew almost sixfold in 1948–1979. The increase in the use of electricity followed the development of industrial production, and in the course of the same period the electrification of all households was practically completed. The development was accompanied by a strong structural change. The percentage of those working in agriculture and forestry dropped by ten percent in the 1950s, and by seventeen percent in the next decade. The public administration system aimed at guiding, regulating, and building up an infrastructure for the society and the economy.

Common to the laws from these different periods is their aim to manage electrical safety. According to Veli-Pekka Nurmi, electrical safety is created through the identification and prevention of hazards, and even with the development technology the basic factors are unchanged. The hazards are electric shocks and electrical fires, and their occurrence can be affected by the actions of human beings. According to Nurmi, electrical fires may be caused by faults in design or manufacture, incorrect installation, insufficient maintenance, and wear, or improper and careless use. Poor connections and components are also sources of hazard. (Nurmi 2001, 7–17).

Market control in Finland today involves all products in the country on equal grounds, which had a part in defining the centralization solution implemented in mid-1990s. Legislation has been further developed so that the authorities have the possibilities of surveillance and the necessary coercive means at their disposal. Market and customer guidance has strengthened, which was one of the objectives filed by the committee.

From the point of electrical safety, this development has meant a shift in emphasis from the surveillance of safety towards securing the competitiveness of companies and ensuring the access of Finnish products to the European market. On the other hand, the reliability of the system shall ensure the safety of products, which is a prerequisite for Finnish products’ access to the market. Thus, the objectives of competitiveness and safety can be simultaneously realized. At least three factors can be found for the development of electrical safety governance.

The first factor is the securing of the position of Finnish industry with trade political means. The emphasis on trade political angle of view is understandable in the social situation of the early 1990s. Finland was in deep recession, and the trade political angle of view guided the legislative solutions. Finland did receive an inspection system conforming to the EEA agreement so that Finnish products could compete on the common market. Objectives in accordance to it were also valid when Finland joined the EU in 1995.

The second factor is the search for solutions that are in line with the changes in administration. The amendments aimed at a solution where the ministries no longer would act as the surveying authority, and the task of surveillance would primarily be transferred to local administrative authorities or other units of the central government.

During 1990s there were repeated attempts to develop the ministries into strategic centres and headquarters of the government. Therefore, administrative routines should be carried out either in units of the central government separate from the ministry, or in local administration. If the operation in the field requires specialization and unified practices, a centralized solution is founded. According to the idea of decentralization, decisions should be made as close to the customer as possible, and unnecessary handling of issues in multiple stages should be avoided. What speaks for a local solution is that the operation requires local expertise or close connections to the customers. Of the guiding systems especially output guiding has also decentralized administration. In other words, there have been major plans for renewing central government, such as the proposal on transferring to a single stage administrative model, and the state corporate project, but the big plans have shrunk to smaller practical development operations.

Thirdly, besides external factors, reasons for the solutions that were made can also be sought in the very nature of the operations. The reason behind the reformation in the mid-1990s was partly the general aim to make the operations more effective through organizational solutions. On the other hand, the financing structure of SETI was more and more based on commercial operations. Alongside this it was necessary to maintain the authoritative operations that were clearly distinct from the commercial side in decision-making as well as budgeting.

The basis for the present system lies in the EU directives enforced through national legislation. Each EU member state defines independently what kind of organizations are taking care of the obligations to implement the Community laws in their own country. This is a central principle because according to the founding agreement of the Community the implementation of Community level decisions belongs to the member states. The TETAHO report on electrical safety also puts forth the general principle that the member states can decide themselves how they administratively arrange the implementation of their responsibilities arising from Community laws. A member state cannot, however, deviate from the distribution of tasks between the controlling authorities and the notified institutions as stated in the directives.

The European Union directives do not define what kind of organizational model is used for implementing the union’s objectives; it is an internal matter of each member state. The Community directives presuppose only that each member state arranges surveillance in a proper manner (CIM).

In the new situation, the organizational solution for segregating the control and inspection operations was created first, and the new Electrical Safety Act was passed after that. The law on TUKES was passed in 1995, and the new Electrical Safety Act in 1996. Central to the arrangement of authoritative operations, the law on the CE marking (1376/1994) was passed already in 1994.

The second paragraph dealing with the level of electrical safety* The requirement included in 5:1 § of the law is extremely strict. It contains the idea that all hazard situations caused by electricity are considered to be against the law. This applies even to situations where nothing happens. Merely to cause a hazard is forbidden by the law. contains the objectives placed for electrical safety and they are described briefly as follows (source: Safety Technology Authority TUKES):

Section 5

Electrical equipment and electrical installations shall be designed, constructed, manufactured and repaired, and serviced and used in such a manner that:

1) they are not hazardous to life, health, or property;

2) they do not cause excessive electric or electromagnetic interference; and

3) their functioning is not easily disturbed by electric or electromagnetic interference.

Section 6

The Ministry shall issue the provisions and regulations necessary to eliminate the risk of interference referred to in Section 5.

Section 7

The Ministry may provide that the provisions on electrical equipment contained in this Act be applied to certain electrical installations comparable to electrical equipment because of its method of manufacture or use.

The Electrical Safety Act of 1996 was passed as a general act in the way presented in TETAKO (1992, 29) so that the enforcement and amendments of the technical contents of the directives could be implemented using statutes and decrees of lower level than acts. This was necessary because the EU directives could be divided in legislation between several acts and statutes, decisions by the Council of State, ministries, central administrations, and inspection institutions, as well as standards approved by the Finnish Standards Board. And, indeed, SESKO published in 1999 in cooperation with the Finnish Standards Association (SFS) the SFS standards concerning low voltage installations and electrical safety. They replaced the earlier regulations by Inspection Centre for Electrical Apparatus. The preparation of laws and the issuance of regulations binding the electric field of operation was now a task of the Ministry of Trade and Industry.

Founded on 1.11.1995, the Safety Technology Authority (TUKES) was a new Government office for handling tasks concerning electrical safety and other matters of technical safety, and all the authoritative tasks previously handled by Inspection Centre for Electrical Apparatus and The Centre of Safety Engineering were transferred to it (Parliament HE 89 – 1995 vp). According to its authoritative task, TUKES surveys the realization of electrical safety in Finland and the operations in the electric field of business. Among the central tasks transferred from SETI to TUKES were the surveying and authoritative tasks concerning electrical safety and the issuance of administrative instructions clarifying the regulations.

The technical inspection tasks related to electrical safety are carried out according to the decisions of the Ministry of Trade and Industry (Cf. TETAHO 2002, 68). They define the aimed level of safety, but the models of solution for reaching the level of safety are defined elsewhere, primarily in standards.

An evaluating institution notified by the Ministry of Trade and Industry grants qualification certificates. TUKES grants qualification certificates that give the right to operate within the area of qualification stated in the certificate (MTI 516/1996).

Return to remote government control

In the Grand Duchy of Finland the use of electricity spread rapidly from the 1880s onwards. The needs of industry and households began to emerge and they created a market for new products. In this sense the «Tsarist Age» was not at all stagnant. This is reflected in many details in our material. Since the 1890s documents are widely written using a typewriter, and at least since the 1910s the central terminology is beginning to be established in administrative use. The authorities responsible for electrical safety administration allow the operators within the field to define their own ways of operation, and public administration secures the practices with legislation using very general terms. The authorities are not in any significant way preventing the transfer of international influences to electrical safety work. What is said above contains many features that are characteristic to electrical safety governance in Finland in the early 21st century. Electrical safety is largely based on practices created within the field itself, and these are secured by general legislation.

The electrical safety system in Finland has clarified since mid-1990s, when authorities lower than the ministry were deprived of the right to issue obliging norms. In practice, the norms that had been issued by lower than ministry level authorities and that were desired to stay in force were transferred into decisions by the ministry. The other norms issued by authorities lower than the ministry were revoked.

In questions of electrical safety the State of Finland and the European Union represent the public authority. The means they utilize for reaching the objectives are not restricted to legislation but means of many levels can be used for control. The means of the Community are statutes, directives, decisions, and recommendations. Executive power and the right to issue norms, on the other hand, lie with each member state. Public control is directing the choices of companies and citizens at many levels. The amount of controlling material is so extensive that it is not possible for a single operator to handle and fully manage even the material concerning his own field of operation (Cf. Harisalo 1997, 12–13, 65).

Alongside legal norms, standardization and quality policies complement legislation by creating comprehensible and applicable entities out of extensive objectives. Standardization and quality policies are, thus, promoting the objectives of good governance. However, Governance in the early 21st century starts with the paradigm that to achieve objectives, quality management is a more effective and faster way than obliging regulations. In the development of inspections you can see how enterprising reflects industrial corporatism and the tendency towards self-regulation on the basis of guilds. This is where standardization system and quality policies are needed today. The Electrical Safety Act of 1996 passed as a general law, and the extensive self-regulation within the field have created the framework for modern corporatism.

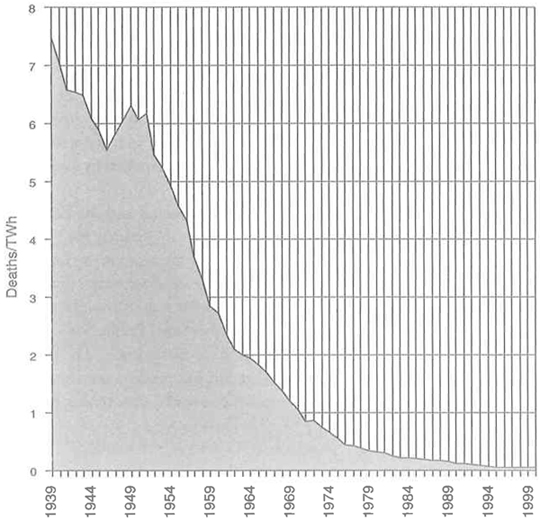

EEA membership and Finland’s possible EU membership, and the development necessary for the field forced the centralized organization of Inspection Centre for Electrical Apparatus to be dissolved. Other than administrative factors have also affected the number of fatal electric accidents, as shown in the attached diagram. Of the isolated factors we can mention that the construction work related to the 1952 Olympics increased the number of fatal accidents. The reason was partly the use of unskilled labour in construction work. Similarly, the increasing number of mobile cranes in the early 1960s also resulted in more fatal electric accidents. Increasing awareness of electric hazards, the decrease of downright negligence, and technical solutions increasing electrical safety have decreased the susceptibility to accidents over the whole century. In the past 50 years, the number of fatal electric accidents has not increased under any model of electrical safety governance.

Fatal electric accidents in Finland 1939–1999

(Source: TUKES).

During the different models of electrical safety governance safety has, however, increased if the number of deaths and accidents caused by electricity is used as the indicator. Electrical safety seems to have developed for a number of reasons irrespective of administration.

The Governance in Finnish electrical safety generated during 1990s returned to its roots a hundred years back if we consider the fact that cooperation between and voluntary action of operators within the field, i.e. a model of operation based on social capital, is again emphasized as the basis for organizational solutions. This tendency is supported by the general law of 1996 that does not go very deep into detail.

New governance emphasizing effectiveness and consumer’s status

The essential feature of the present system is that the evaluation results by notified institutions are also acknowledged in other member states according to the reciprocity principle. Thus, a member state cannot prevent the introduction of products that have been properly evaluated and verified to conform to the requirements as demanded by the relevant directive. The system promotes the movement of goods within the union and also enables competition between the inspection institutions notified by the member states. The institutions notified by the Finnish government are able to offer their services in other member states and the institutions notified in other member states can do the same in Finland. In addition, the EU and countries outside it have reciprocity agreements based on the so-called MRA agreements and PECA protocols. Thus, the evaluating institution can be located, for instance, in the Czech Republic, Hungary, the United States, Canada, Australia, or Japan (TETAHO 2002, 33).

In the early 21st century one of the tasks of the surveying authority is that the operators within the field trust each other through following the electrical safety regulations. The authority will also observe the consumers trust in electric products. This presupposes not only functional surveillance but also the distribution of more and more information on electrical safety among operators as well as consumers within the field. The above means that the authority has the responsibility to promote electrical safety using the available means, although the main responsibility for ensuring the safety of the devices has been transferred to the manufacturers.

At the moment, sovereignty of the consumer and efficiency are the central factors forming the governance of electrical safety. The consumer’s views are esteemed in all respects, in the foundations for decision-making as well as in service practices in the form of customer-orientation. Arguments will change with the times, and the governance receives its foundations from new factors. It is also clear that risks are involved in the system in a situation where high consumer safety and, in accordance to market control, the producers’ own responsibility are simultaneously emphasized. There is a threat, that if hazardous products enter the market in great numbers, the credibility of the whole system will be jeopardized. Typically such situations are tackled by increasing the strictness of control or by adopting higher sanctions for breaches.

References

Aarrevaara, Timo: Institutionaaliset uudistukset Euroopan unionissa. Helsingin kaupungin tietokeskus 2001.

CIM: Completing the Internal Market: White Paper from the Commission to the European Council (Milan, 28–29 June 1985) COM (85)310.

Harisalo, Risto: Euroopan unioni elintarvikealan sääntelijänä – yritysjohtajien näkökulma julkiseen sääntelyyn. Tampereen yliopisto. Hallintotiteen laitos. Tampere 1997.

MTI: Decision of the Ministry of Trade and Industry on work within the electric field of operation 516/1996

Nurmi, Veli-Pekka: Sähköpalojen riskienhallinta. Tukes 2001.

Stenvall, Jari: Käskyläisestä toimijaksi. Valtion keskushallinnon pätevyyden arvostusten kehitys suuriruhtinaskunnan alusta 2000-luvulle. Acta Universitatis Tamperensis 759. Tampere 2001.

Syrjänen, Olavi: Byrokratiasta businekseen. Hallinnonuudistuksen oikeudellisia ongelmia. Valtiovarainministeriö. Hallinnon kehittämisosasto. Edita, 1996.

TETAHO. Teknillisiin tarkastustehtäviin liittyviä hallinnollis-oikeudellisia kysymyksiä selvittävä työryhmä. Kauppa- ja teollisuusministeriön työryhmä- ja toimikuntaraportteja 4:2002.

TETAKO. Teknillisten tehtävien ja viranomaistehtävien erottaminen teknillisessä tarkastustoiminnassa. Kauppa- ja teollisuusministeriön työryhmä- ja toimikuntaraportteja 20:1993.

University of Tampere,

Department of Management Studies,

Finland

University of Lapland,

Department of Administrative Science,

Rovaniemi,

Finland