Reflections on Health and democracy – proposals for interdisciplinary projects

Michael 2004; 1: 221–30.

There are at least three different discourses connecting «health» with democracy» today: First, there is the problem of democratisation of the health sector, within a political economy perspective or a feminist perspective. Second there is an attempt to use health science concepts as metaphors in political science discourses concerning the performance of democratic institutions. None of these discourses will be addressed here, as I will concentrate on a third theme: In what ways does democracy foster health? How can we model a relationship between democratic practices and the health condition of people living within a political constituency? What are the gaps in knowledge when we want to discuss the merits of democratic practices to health, and how should these gaps be filled by interdisciplinary research, involving social scientists and the health sciences? These grand questions can only be handled in an impressionist way in the present essay, as my research in local government processes – at least at first sight – is only marginally in touch with public health issues.

Democracy defined

«Democracy» can be defined in many ways. In discussions of health and democracy, the distributional effects of democratic practices are often highlighted, such as economic equality, gendered equality and the democratically based welfare system’s ability to function as a safety net for disadvantaged groups. In the present discussion, democracy as a process of popular participation, rather than its effects will be given priority. And in this respect democracy means more than voter turnout at national elections, and the way the elected representatives follow the mandate given by the electorate. In addition, democratic participation means that ordinary people are taking part in discussions and opinion formation around issues of collective problems in their community – be it at the level of the locality or the nation – and their solution by political measures. Sometimes people arrive at a consensual decision, which is the deliberative political ideal. Sometimes political participation means the opposite – an escalation of community conflict – more in line with the idea of political competition based on conflict of interests and values.

Modelling democracy – health relations

With a professional background in local government studies, my competence is within the health side of the democracy – health relation is very limited. The WHO definiton of Health – a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity – seems to be suited for a discussion of health’s relation to democracy understood as citizen participation, as the definition includes a social element as well as the physical and mental elements.

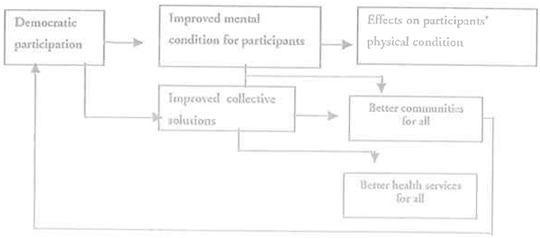

To model a relation between democracy and health, the relations may be specified like in the following, where «democratic practices» refer to activities at certain territorial levels (municipality, region, state) that are governed by a democratic institution.

Fig. 1

«Democratic participation» in the upper left corner is here the independent variable that is thought to be productive to the health standard of a community in two ways. First, by the effect that participation has upon the participant, and second, by the effect participation has on the quality of the decisions and policies.

In the first row, the effect of increased democratic participation upon the individual is understood as the democratic experience in itself–the feeling of exerting some power, and the social benefits from participating in discussions, of attending rallies etc. – contributing to the individual’s health condition, by the «mental» way. Exactly a high degree of participation means that these effects reach a substantial part of the population, not only a few democratically elected officers in local government. On the other side, there is little reason to expect that the ones positively affected by the practice of participation will be the more deprived parts of the polity. Attending political meetings and paying party membership fees in the post-industrial age is something definitely «middle class». As to effects on the physical condition, these may be more dubious (we will return to that issue). People may be feeling good by getting engaged, but this does not mean that these people do the «right» things as to life habits.

The second row specifies how increased democratic participation may lead to better problem-solving and collective solutions. There are two effects of this that may be relevant to health: First, the creation of an allover better social environment equipped with good schools, safe roads and accessible parks and playing grounds. This is supposed to create a better local, regional, or national community, with implications for social well-being and, in the next step, (possibly) physical and mental health.

The second effect (third row in the model) is the direct connection between democratic practices and health, which is the situation when democratic participation enlarges the local political agenda for health issues and their solutions. This effect is also strengthened by actions of voluntary organizations based on democratic participation, in the field of health issues and patients’ rights.

The model thus shows both benefits that are intrinsic (for participants) and benefits of the public-goods type (for all) resulting from increased political participation.

There is of course a interlinking of the causal chains, and there are backward loops from improved health and community solutions that may positively or negatively affect democratic participation. Successful policies at the level of the community (row 2 and 3) may stimulate democratic participation, but they may also have the opposite effect: Successful development of expert-based health services may render democrartic participation in that field unnecessary and a nuisance to the expert-system people. Once a service has obtained legal protection, public funding and professional staffing, further popular participation support may – at least for a time period – be thought of as unwanted. «Democratic inactivity» may be preferred both by the electorate, having obtained its political goal (e.g. the establishment of an important medical service institution), and by the personnel, not wanting lay people to meddle in affairs that the professionals are well trained to decide on themselves.

Putnam and the social capital discourse

The reasoning presented above is inspired by the interdisciplinary research effort made by American political scientist Robert Putman and his associates since the 1990s. Putnam and associates re-launched the concept of «social capital» to analyse variations in public sector performance. Starting with a study of the Italian public sector (published 1993), and culminating with the publishing of «Bowling Alone» in 2000, Putnam and his associates have set the agenda for a new discussion of what makes democracy – and society at large – work.

Putnam’s findings are in no way revolutionary, as they are based on well-known and corroborated facts like the relation between social in integration measures and quality of social life indicators in cities and countries. To be more precise, Putnam can be said to have rediscovered the relation between one specific mechanism of social integration, namely the participation in voluntary clubs and associations (including political parries and trade unions), and its relation to societal values like a well-functioning public sector, safe communities, and economic development (Putnam 1993). In «Bowling alone» Putnam reformulates the relation between public participation and socio-economic qualities on a more general level, by discussing collective activities in its broadest sense and its effects on a wide range of societal qualities, including «Health and happiness» (Bowling Alone, chapter 20).

The very simple idea is that when people are co-operating on a voluntary basis, society will improve, and so will the welfare of the individuals. Hence the provoking title of book «Bowling Alone»: According to Putnam, Americans are attending bowling halls just as much as before these days. The difference is that they are not bowling in teams and leagues to the extent that did some decades ago – today bowling is more of an activity you perform alone, at times that fit into your (tight) time schedule. This is very much the same as the move from the formerly popular sport clubs- based fitness group sessions to «Health studio» individual attendances. According to this reasioning, the refined fitness machinery and the professional advice the customers are offered at the modern health studio are of less value than the more outdated fitness groups coming weekly together to perform stretch – and – bow – exercises. The social component, according to this view, compensates for technological refinement and professional advice.

«Togetherness» – in Putnam’s sense of the term – is important to society by a series of mechanisms; they can be listed as:

building trust, as there is an expectance of everyone taking her/his turn, and thus there will be a hindrance to the practicing of free-riding,

enhancing empathy, as one is likely to take into account not only a mechanical division of labour, but also the views and context of other participating colleagues,

building a collective identity, as people joining a club will identify with the collective unit, and this will possibly form one stabilizing pillar of the individual’s self-identity,

creating equality, as there is an inherent expectation of reciprocity in collectives, and the mechanisms for reaching decisions will be based on one individual – one vote. The political equality of the organizations will influence the members’ conceptions also of economic equality (in any case people will start thinking about economic equality when discussing the size of the membership fee),

providing welfare solutions by collective problem-solving. It is evident that collective action produce collective solutions that enhance the welfare of its members, for instance within health-promotion,

bringing help and safety to individuals: By being a member of a group someone will notice if you don’t show up at a meeting and perhaps pay a visit if you are sick,

reinforce good habits: Coming together may mean a pressure on not smoking, on preference for ecological products etc. Often the one with allergies or the one very conscious on ecological consumption will influence the ways other behave,

provide arenas for socializing and recreation that may recruit outsiders.

Thus the key issue will be how to create and sustain institutions that underpin collectiveness of an inclusive kind. By «inclusive kind» we mean collectives that can easily be joined by everyone irrespective of race and social position. Exactly in this lies a challenge, because many organizations are formed to attract specific groups of people and are by definitional or economic criteria, closed societies. Such groups may of course enhance the well-being among their members, but they may at the same time lead to more inequality in the society at large.

Family life and friendship relations are good examples of «closed societies» – they may significantly enhance the living conditions of their members, but family life and friendship are structures that have no positive effect on equality and an equal distribution of political power in the society at large. Putnam even writes on «amoral familism» in his study of Italian society.*Putnam 1993:88,92.

The institutions that qualify as democratic and open are:

1. Elected local government institutions, councils, committees.

2. Local political party organisations

3. Voluntary associations, such as sports clubs, trade unions, choirs, congregations

4. Neighbourhood formal or informal associations

There is a ranking of the institutions in the listing above: At the top are the local government institutions, such as serving on the municipal council or in one of its committees. Anyone can be on a list for election – and in smaller municipalities a substantial part of the population will have served on local government committees at least once during the lifetime.

Especially in the Nordic countries, the municipalities have a broad welfare responsibility, and at the same time they are deeply engaged in civil, cultural life, as well as in societal development work related to commercial activities. Not few people participate in municipal affairs – in the smaller municipalities a considerable part of the local population would have experience from the municipal council or from its proliferating number of subcommittees. A special form of responsibility is demanded from the people participating in municipal affairs, namely the ability to take on a comprehensive view of the needs and possibilities in a given territory – and as these may change almost overnight, the political generalist competence will be enhanced in the population at large. Learning typically takes place by one’s confrontation with The Budgetary Logic, expressed in the question «yes, this is a good idea, but where is the money to come from?»

In the next category come the local branches of party organizations. What are common to these types is their openness and their very broad approach to local level problem-solving. Also, in the political party, the individual member is likely to meet people with other professional backgrounds, sharing the same ideological points of view, but the members are seeing the world through different lenses due to professional or experiental backgrounds.

An interesting aspect of the democracy / health relation should be noticed: We readily acknowledge the strong positive impact on society from the engagement of local councillors and committee members, but at the same time we must remember that they practice their art by sitting rather immobile in chairs around a table for hours; until recently most of them sat there smoking during the proceedings; today smoking must be performed outside, in pauses, but the committee members are still likely to consume snacks, coffee, Coke and cakes continuously or at intervals, and finishing off the evening with at visit to the nearest bar, where more sitting and smoking would be accompanied with the intake of not negligible amounts of alcoholic beverages.

The third type is participation in a voluntary organization, which means very much the same as participating in a party branch organization, only here the focus is not so broad as in parties and in local government, and self-interest is more to the front (e.g. in trade unions). And socializing is even more frequent than in the local government system, in fact some organizations only mobilize its members when the annual or seasonal feast is going to take place. Nevertheless, the democratic impact of organizations is clear, as they always operate by one-person-one-vote rules, and the members, represented by the annual meeting, is the formal power base.

The fourth form is the informal but inclusive neighbourhood arena – or the formalized neighbourhood group – at times even acknowledged as part of the local government system in a form of decentralized municipal government scheme. The neighbourhood arena may be one of the most inclusive ones. If it functions well, it will mobilize all people in the neighbourhood for physical improvements at the area as well as regular socializing events.

Close to this form is the ad-hoc political action campaign, fighting for a specific local cause by mobilizing a large number of people affected.

Machers and Schmoozers

These formalized organizational forms of democratic participation should be discussed in relation to informal socializing for no cause whatever, but based on family ties or friendship. This means the practice of visiting and entertaining on a reciprocal basis, which is often thought of as strictly civil and private activity – which it of course is. At the same time, the reciprocal processes linked to kinship and friendship may have some of the positive effects listed above, pertaining to collective behaviour in general. In «Bowling Alone», this is one of Putnam’s creative points: The criterion for collective behaviour should be everything social that exceeds the primary family or the dyadic friendship relation. Putnam distinguishes between «machers» – the organizational people with dear aims for their participation, and «schmoozers» – people that enjoy the company of others, Just for its own sake.*Putnam 2000: 93-95 By bringing «schmoozing» into the political participation discourse there is the expectation that outsiders will be added to the primary groups as time goes: The kinship gatherings will bring in new-comers when new family relationships are formed, and the friends-of-friends mechanism will bring newcomers in and thus extend a friendship group. Kinship and friendship based «coming together» will therefore tend to involve more persons, and the discussions and points of views expressed at such gatherings will thus tend to be communicated also across groups. It is exactly this last point that links the informal gatherings of friends and kin to democratic practices. Politics and democratic practices depend on informed citizens and that the ideas and preferences are signalled to the elected representatives and to the party members.

It is rather obvious that democratic practices thus spelled out in the form of formal political organizations, voluntary organizations, neighbourhood initiatives and informal socializing will be conducive to mental as well as to physical health. The mechanisms at work here, I think, from a layman’s perspective, must be the positive mental effect on people that participate and socialize. It is perhaps a more pending issue whether secondary effects, on physical well-being exists, but at least we will expect that participation (social or political) will trigger a mechanism for repressing the pains from, and worries over, a bad health condition.

At the same time, it is obvious that socializing and coming together for collective problem-solving means that people eat more fat burgers and pizzas, they drink more beer and Coke, and they feel more free to smoke. Often the coming together means sitting around tables, much more so than the occasional dancing and other physical practices also typical of organizational life. In short, many of the more recent health rules and measures against smoking, immobility, obesity and junk food are likely to be violated by the same mechanism that provides a stronger mental health condition.

Guidelines for health /democracy projects: The community approach

There are some intriguing aspects of Putnam’s research. If it is so that well known conventions of organizational and political, and even social participation leads to better health conditions, then we need research of the applied type, identifying and testing means to underpin the type of social behaviour that produces health. Advanced research on the mechanisms by which participation leads to better mental and physical conditions will be another part of the approach. The linearity of the model is only hypothetical, we know for instance that elected officials, confronted with the need to cut services and lay off personnel in regimes and municipalities of the right-wing type will often be exposed to stress, compared to politicians who can champion new welfare state monuments for the benefit of their electorate. Putnam, however, especially in his 2000 volume is much more concerned with a discussion on finding practical methods to re-engage people in well-known practices, as political, organizational and even schmoozing practices have weakened – at least in the USA during the last decades.

To propose projects on democracy – health – relations along this line of reasoning should, in my opinion, take the territorial unit as its starting point, which means case studies of a limited number of localities. It would be wise to select municipalities or neighbourhoods for study in which there have been serious attempts at stimulating political participation during the 1990’s.

A series of participation experiments and more lasting measures have been tried out in the decade defined as one of citizenship decay, individualism and customer/ client-orientations in people’s dealing with local authorities. We may mention Local Agenda 21 as one measure that may have had an effect on citizen participation. Other experiments have been the free-municipality arrangement. When selecting municipalities in which specific measures have been carried out, the potential value of the projects may be greater, because one will not so easily find that rich, middle class social environments produce more participation – and health – than do deprived, job-losing areas. It will also be interesting to compare the merits on different forms of stimuli to participation as to their effectiveness both on lasting participation, and on health indicators. Paired municipalities in different categories of size would be necessary to establish a control group, but of course one should try to keep some basics constant, in the form of occupational structure and income levels.

The above must be treated as preliminary reflections on a highly interesting theme, challenging to scientists, as the solutions and means searched for will not necessarily be of the expert advice type, but of a facilitatory kind that the local citizens themselves will be able to discuss and to decide upon.

References

Putnam, Robert D. with R. Leonardi & R. Y. Nanetti (1993) Making Democracy Work. Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Putnam, Robert D. (2000): Bowling Alone. The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

nilsaa@sv.uit.no