Exploring external and internal public health concepts

Michael 2004; 1: 193–205.

The wilderness of public health

An old saying goes like this: «When walking into a forest you will see more and more trees». These are simple words asking for reflection and reconsideration. Penetrating a problem always implies that you discover ever more to think of all the time, so also within the field of public health. New demands, new questions and even new criticism appear constantly. In which way should public health sciences and practices develop? How to handle? Is there a key, a sort of common denominator which can be of help? This paper argues that central health concepts and the changes in them may play a central role, and that exploring concepts, shifts and their consequences for the health of the population in a systematic way might be of help, especially when seen in a public health perspective*For Nordic readers, general thoughts about the place and scope of public health has been discussed by several authors in the 2003 textbook Larsen Ø & al. (eds.) HeIse for de mange. Oslo: Gydendal Akademisk..

The first glance and the following

At the encounter with a health issue, e. g. the complaints of a patient or a public health problem, even if the case looks clear cut at the first sight, a more close approach will usually reveal a series of attitudes and concepts attached to it, all of them subject to degrees of constant change.

An example: The patient seeking your advice and your treatment for her sunburn has a problem mingled into a complex cultural context. At the bottom line, to see a doctor for a sunburn, instead of treating it with some home remedies and endure the painful punishment for a sunny day at the shore, is on the one hand a marker of some step at a health perception ladder, on the other hand a sign of affluence. But it may also reflect attitudes shaped by health information or media, dealing with health hazards related to sun tanning. What counts the most to the young lady, the perceived value of a certain hue of the skin, versus the prospects of health risks in the short and long perspective? Therefore, her impetus to call at the surgery may be prevailing, highly non-medical attitudes towards what beauty and attractiveness is like. As a doctor, what kind of responsibility do you have in this case, and how far does it extend itself? After having taken care of her immediate pains, you probably will give her some advice for the future and you will also have talked more in general to her about people which are careless about suntan. But then you have transferred the problem posed to you into two new spheres. In the first sphere this is into the time dimension of the patient: Short sight sunburn and long time cancer risk. In the second it is into the sphere where the patient is only one of the individuals of a population suffering from the sun. This last one is the sphere covered by the discipline of public health.

Another example: As a community health officer, you are presented to complaints from a fellow citizen: His neighbour’s affection for cats has materialized into a crowd of filthy and smelly pets, living on the other side of his garden fence, perusing his children’s sandbox as their toilet and yelling all the night. The immediate and individual problem has to be solved both for your client and for the cat-owner, a task tricky enough. But the time aspects and the community aspects are present also here. How to avoid repetition of the grim story? Preventing new cats from entering the scene belongs to the shorter perspective, but on the long run: How to avoid cat problems in general for the community? Launching of information campaigns? Submitting proposals for enforced local legislation?

The old saying is appropriate also here. The first of trees you see at the start of your forest wandering, immediately points to several others. Perhaps the solution of your problem has to be sought by approaching one of the other targets instead of the one you saw at first? Especially in the field of public health a need is felt to explore the options, from the scientific basics down the line to practical implication.

A framework as a conceptual tool

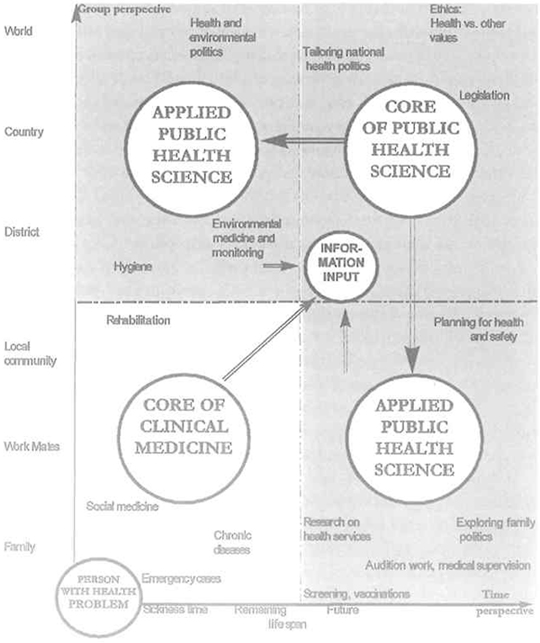

To discuss this topic, let us use a medical task or health problem as our point of origin, as shown down left in figure 1 on page 197. Imagine a horizontal line stretching out from it, a time axis starting with the immediate and running out into the future, representing the time perspective. Vertically, an ordinate represents the scope, running upwards from the personal sphere to the general, e.g. from the very individual action of, say, removing a metal particle from a red eye, up to the general prevention of such mishaps by introducing mandatory eye shields in all welding industries in the country.

These two axes are continuous of nature, but both of them have some natural breaks. Most important are the points where time and scope leave the ranges covered by the life and interests of a single person, points on the axes which may vary in position according to the issue discussed.

In clinical medicine considerations, the individual range of time can be measured in days, as the expected duration of a cure, up to the logical endpoint constituted by the remaining life span until the patient’s death. Beyond this point, the individual approach may imply an evaluation of the treatment given or include preventive measures taken to avoid new persons falling victim to the same health impairment.

In most cases, however, even very individual medical issues will implicate others than the individual, and more or less become a collective problem. You will move upwards on the individuality ordinate: Influences by and on the group to which the patient belongs: Family, colleagues, working environment, social network, community. But the ordinate stretches further upwards and out, passing through the local community into the society at large. Again, there is a natural break, admittedly also here somewhat vague, where the ties to the individual case vanish and the issue becomes a general one.

The diagram (figure 1) with its two axes pointing to time and social space can easily be converted into a framework which may be even more useful: Lines pulled at the natural breaking points render a set of four boxes, which identify four quite different arenas for medical work. Each of these boxes has objectives, methods, and underlying concepts of itself, but nevertheless they are part of the same medical universe. Let us look at each of them:

Short sight solutions for the sick

The box for swift solutions down left in figure 1 is the frame where most clinical medicine belongs. Immediate diagnosis, treatment and relief as soon as possible are in the main interest of all parties involved.

However, the nature of the medical problem itself is a basic point. Even here you are dependent on prevailing attitudes and concepts. It can be claimed that many of the problems presented are culturally determined, and also that many of them simply are man made, if we explore them more deeply*See e.g. Larsen Ø. Health care and attitudes in health matter. Paper delivered at the Phoenix network conference, Braga, Porrugal 2004. In press.. The consequence of course is that the cultural setup and the cultural changes should be targeted, a quest for action in the three other boxes.

Of course there exists a biologically based morbidity and mortality, but it is often that the perceived morbidity and mortality, the mere experience of fearing or suffering from a disease, causes more worries than the biological process itself. Here, changes in attitudes may influence day to day medical work deeply. A growing individualism as in modern Western societies goes hand in hand with an increasing health consciousness, which promotes perceived morbidity and alters medical demands. Are the processes on individual and population levels steering these changes sufficiently studied? A better future handling of such health issues probably require basic research. There will be a need for competence beyond the medical, belonging in the upper right quadrangle of the figure. And the acquired knowledge will depend on non-medical agents and non-medical considerations in order to be applied in the short sight community level box up left in the figure and the long perspective patient oriented sphere down right in figure 1.

Realizing that a medical problem presented as a rule also affects the patient’s personal contacts, makes a wider scope necessary and should shift the interest upwards on the ordinate. The fact that the actual disease might affect the patient for the rest of his life draws the attention along the time scale. However, such approaches are basics in every medical training programme. A good doctor should be, and usually is, proficient in most of what is going on in the lower left box of the figure, the individualistic and short sight one. A commitment to the patient in front of the doctor lies in the core of clinical medicine and is also in line with the essences of medical ethics.

But what about the three other boxes of the figure? Medical work where commitment adheres to the population and its future health?

FIGURE 1: THE FRAMEWORK OF CLINICAL MEDICINE AND PUBLIC HEALTH

Three boxes of public health

Research, strategy, and setup of the society

The hallmark of public health thinking is the group perspective, aiming at long term health benefits for the population. Up to the right in our metaphoric figure you will find the core of public health. Here, the scientific basis is established for how social and physical environment is a health determinant.

Constant streams of data and feedback should constitute the soil for public health science, the more, the better. The more quality assessed and the more specific, the better. Epidemiology tells about frequencies, distributions, causal relationships, monitors shifts and provides hypotheses and theories. Medical anthropology reveals what is going on in people’s minds and alerts when shifts occur. As a lion’s share of our physical and social environment is man made, and as the shifting levels of acceptance for medical problems and medical care are results of a long historical development, the background is set by facts and clues provided by medical and social historians, social scientists, social geographers, psychologists and researchers from fields related to public health and its context. Specialists on society may assess former efforts and processes and give clues of relevance for the future. Examples: What about effects on health exerted by political decisions in other fields than medicine? Decentralisation/centralisation? Taxation politics? Etc. And what about cultural traits? Architecture? City planning?*See Larsen Ø. Boligmiljo og samfunnsmedisin. Oslo, Institutt for allmenn- og samfunnsmedisin, 2000. E.g. in the case of housing policy, it can easily be shown that a market oriented housing policy clearly conflicts with commonplace public health knowledge about the impact on health conditions exerted by social investments, social coherence and voluntary networking and stability.

Methods are developed in order to implement the acquired knowledge and to transform it into practical measures in planning of the society, on levels ranging from the local environment to the international society, using and recommending techniques along all the scale from social psychology over geographical planning and national legislation to international politics.

However, far up to the right in the figure, far out and dominating, lie some overruling questions: Exploring the value of life and health in general as compared to other values. What does society in fact accept of bad health and impairment, and how much health do we really sacrifice in order to achieve other goals? As long term, population-oriented thinking often collides with liberal market philosophy; the most important decisions for the future of public health probably will be taken on the political arena by nonmedical actors who should be provided with public health knowledge and arguments. Changes in concepts will be a core issue.

Strongly connected to philosophy and ethics, such questions should attract considerable interest. Guidelines should be set up, clearly be discussed in public and by professionals, and finally be revised into recommendations with wide acceptance. Historically, changes in the evaluation of health are appalling. It is an important task of practical bearing to monitor the changes in concepts in this field and to consider methods for changing attitudes.

Environment, social services and health management

One extension of group intended, long perspective public health where public health science becomes an applied science, protrudes into the long perspective individually directed box (down right in figure 1), where general principles are made operational and introduced into practice to maintain the health of the prevailing population. Vaccination campaigns, health promotion issues and screening programmes belong here*This is the field of most standard textbooks of public health, and special references are not given here..

But there is another increasing working field for public health officers and for putting their skills and knowledge into life: The audition function belongs in the metaphoric box of individual concern in a long term perspective. These functions gain steadily in importance for the time being. To be a controller, supervising that quality assessment regulations etc. are followed, is e.g. in Norway a core activity for the public health agents on the county level. This work poses special requirements to the theoretical background, to the methods and to the auditors themselves in order to play a positive role and to avoid being regarded as sand in the machinery.

The development of health security systems should also be regarded as a public health issue in the individual, long term range. However, practical counselling and guidance of individual clients and patients according to prevailing legislation belong to the tasks of clinical practice, even if the base of knowledge belongs to public health. E.g. in the minds of medical students, this fact may lead to confusion about what social and preventive medicine are like; individual social counselling and preventive advice are parts of clinical medicine putting public health knowledge into life, but not the disciplines of social and preventive medicine themselves.

A new field is the concept of health promotion, which has a need to be explored for traits fit for being influenced. In this respect some tendencies in modern administration development should be addressed: In the welfare state of a post-modern democracy there is an increasing distance between the overruling policies and priorities on the one hand and the practical handling of clients, patients, and social issues on the other. Ethical dilemmas necessarily look different in e.g. the eyes of parliament members passing a budget, where the task is to balance conflicting interest according to a major governmental policy. The comparison is the dilemma encountered by e.g. the home visit nurse who sees that the demand for home services which confronts her, exceeds the resources by far*The Norwegian social anthropologist Hallvard Vike has used this example in his texts, see e.g. Vike H. & al. (red.) Maktens samvittighet Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk, 2002.. This distance between principles and practice, between the top managers of health problems and those who suffer from them, has been settled and exaggerated in recent years. In the modern introduction of an increasing administrative staff, it has been shown that the strategy often has been to delegate the ethical dilemmas down to a level where compliance with directions from above seems to be impossibility.

The accelerating use of economic terms in health management is part of the same process. Money is by nature a tool for comparing values. When health budgets are low, as compared to, say, the budget for road construction, this means that health is given a lower priority than roads for commuting. However, if e.g. a roundabout is built in order to avoid accidents, this may be a public health priority.

Prices of health services and health outcomes are often arbitrarily set, simply because they belong to different value systems. Still, health as such has not got a monetary value. But prices serve as transforming accounting tools for non-accountable values. Although these tendencies mostly are universal, the heavy weight of health in politics and people’s minds makes the development and shifts in attitudes and concepts important, not least because they assault basic values of democracy: Even on the local level loyalty to the locals has to yield to loyalty to the authorities above. The need for keeping inside of the approved budget frames shifts even the local politician’s role from being the representative of his voters into the role of a guard, protecting values given from levels above. Structural changes in society, such as fusion of municipalities into larger regions etc., may reduce the real democratic influence in local societies even more.

However, if the steering by economy is seen together with the administrative delegation of dilemmas mentioned above, health issues end whereother scales for values have to take over*In the 2003 textbook edited by Larsen & al. Professor Anders Grimsmo argues for the necessity of launching bottom-up strategies in the local society to counteract the top-down steering.. An example: When there is no money left to care for the elderly in a proper way, the home visit nurse may choose to do the work anyhow. She is guided by other values than money: Her feelings of moral responsibility, commitment to her clients, ethics etc. Such steering by means of financial inadequacy, increasingly common in many fields, is a phenomenon which should be further studied also from a public health perspective. In the field of health it has been talked about a reservoir of costless care which is mobilized for free by means of financial inadequacy. Astonishingly, this has been no great feministic issue, although most of this type surplus load in the health services is placed on women.

In the armament of public health, appropriate working methods and systematic evaluation of decision, steering, and administration experiences in this field for the time being often are only faintly highlighted.

Another extension from the core of public health also stretches into the future on the individual level. This field attracts increased interest because of the general upgrading of the individual, its needs, preferences and perceptions as compared to those of the group or the population bas a whole. And the downward delegation in newer health management has attained a climax in the school among general practitioners which hails the principle of total patient-doctor collaboration. Then, difficult dilemmas are delegated down to a level where the personal involvement in the problem by the patient in most cases makes responsible decision partaking and optimal solutions unlikely. In addition: Health counselling on long perspective future cancer risk, prevention of cardiovascular disease etc. will face up hill fighting if the personal time perspectives by the patients are shortened.

To tailor individually based health services for the future requires a background far wider than usually covered in any clinical medical specialty. To plan for a society where a multitude of personal choices related to health are made by the individual itself, based on immediate likings and personal preferences, trends and commercial pressures, needs a scientific backing. An example: The physician of the future has to be taught, and has to know how to confront the dying patient with the fact that his fate is a result of own choices.

Coping with rhythms

Up left in the diagram is a box for application of short perspective, group perspective oriented public health activities. This is a field which deserves growing attention. Of course there are medical grounds to be alert: Examples are immediate public health precautions and actions needed in nutritional and environmental hygiene, quick responses to infection threats, catastrophes and so forth.

On the other hand, as a basically long sighted science, public health has to learn how to handle the often dominating short perspectives held by other influential agents in society. Important decisions for the future are mostly taken by politicians in an environment where the perspectives are varying, often short and with elections as important milestones. And with other main objectives than health.

Even if scientific knowledge is at hand, public health sciences also have to develop methods to achieve proper attention to the long term perspective even if there is a collision with other time perspectives. Cooperation on an appropriate level with responsible representatives from the media may belong here.

Three boxes versus one

According to the logics used in this paper, the understanding of the medical sphere would benefit if it was divided into two separate parts: On the one hand clinical medicine with its mostly individual approach and short time perspective, and on the other hand public health science with its mostly long term objectives and a population perspective. The extensions into population based and individual practice make public health also cover two other boxes of the framework in figure 1. There definitely are three boxes of the same kind, contrasting another.

No further research is needed to document that clinical work and public health work in many countries gradually separate more and more. Of course, the increasing amount of knowledge and skills needed both in clinical medicine and in public health leaves a rationale for allowing specialist concentrate on specialist work, and makes a separation understandable. But there are other reasons to be considered: Modern hospitals often operate within tight budgets with few openings for other work than meeting short time core objectives, which are the «production» of treated patients. General practice, even with the group oriented, long perspective name «family medicine» attached, is increasingly commercialised through financial systems, and a strong individual approach with a short perspective is favoured.

It can be claimed that many of the difficulties encountered by public health sciences and public health work relate to unclear understanding of this subdivision of two parts of medical work, which by far have quite different objectives, scientific background, working methods, and agents. Basic concepts are also different, and social and environmental changes important for health may be difficult to assess through clinical medical thinking. Perhaps the two faces of medicine also recruit different people from the very beginning.

It adds to the difficulties that medical work, especially that of the physicians, for a series of reasons has been so strongly linked to clinical practice that many public health arguments are not perceived as medical anymore; simply not belonging to the working field of a doctor. In line with this, public health intervention from the medical side may be felt as disturbing and untimely by politicians, administrators and other agents for the setup of society.

All this is steered by concepts, and probably we do not know enough about these concepts.

Possible changes and tasks ahead

The very first thing should probably be to identify the discipline of public health as something separate from clinical medicine, and especially from general practice (family medicine). In some countries, as e.g. in Norway, the linkage has a historical basis because the health legislation in force 1860–1984 implied local public health officers in all districts of the country, and nearly all of them combined this activity with general practice. It can be claimed that medical education in Norwegian universities still prepares students for medical careers which ceased to exist twenty years ago. The concept of the physician’s role is the first one which should be explored and adjusted.

Another element which carries weight is the prevailing system of integrated medical teaching. This is obviously not the best solution for training the students in population directed, long term medical thinkings, at least not at a curriculum level when they are polishing their clinical proficiency and their overwhelming objective is to become clinical doctors and treat individual patients. In this setting, at the best, issues from the boxes of applied public health manage to attract interest, while main principles are felt more far fetched.

Representatives of public health as a discipline should refine their own concept of what public health is alike. Previously, when preventive and clinical medicine were more intermingled and often in the hand of thesame persons, the public health officers, the image of public health was less problematic. Now, public health includes a series of professionals from different fields like epidemiology, natural sciences, social sciences, humanities, engineering etc., because of the inherent complexity of the field. But the core, the soul of public health science is not included in the role of the individual partaking professions; it lies in the sum of them,in the integrated body of knowledge shaped through concerted efforts. Research, teaching and practice should also be organised that way.

It is a question if the schools and institutions teaching and serving public health are ideal, mainly because they lack the broad and integrated interdisciplinarity which is needed to become heavy and authoritative bases for research, documentation, teaching and counselling, and to act as methodological centres for development of effective applied public health services. But why such centres are only rarely found, again is a reflection of changing concepts which deserve to be explored.

An example from recent public health history: Around 1970, in many countries epidemiology experienced a boost, not least because of rapidly developing computer techniques. New and important connections between man and environment and between man and health related behaviour were unveiled. In the years which have passed, a vast body of knowledge has emerged and still emerges every day. Some places, public health and preventive medicine as disciplines have more or less been identified as epidemiology, a trait supported and maintained by public health publication media. In that way a part of the field more or less conquered the hegemony, leaving e.g. the broad approach by the so called social hygiene from the interwar years of the 20th century behind.

However, what most appallingly has been retarded is the development of methods for implementation, for transforming new public health knowledge into applied public health. We know a lot about, say, chemical, physical and social environmental hazards, the effects of poverty on health, etc. But new and confirming knowledge added, does not help us influence so much the skewed situation. A new systematic approach to what public health really is alike, and to where the strong and the weak points are, is required.

Exploring and adjustment of concepts within public health is a must, and so is the integration of disciplines. Likewise are the external concepts met by public health an issue of itself.

In practical public health work, concepts are encountered all the line down: Concepts about the importance of health as compared to other values, concepts about individual freedom from interference, concepts abouteconomy. Systematic studies of such concepts are still scattered, but should be carried through according to an overruling objective: To strengthen public health.

The trees of the forest

Back to our introductory metaphor: The tasks of the representatives of public health are to see, to study, to learn from and to include in their scope the ever new trees coming into sight.

But still a path is needed.

oivind.larsen@medisin.uio.no